***

Ever since I got my first DNA test results in 2010 I have been researching my Cape Verdean roots from several angels. Of course everything starts with personal genealogy. But for deeper understanding I also take into account: population genetics, historical demography and cultural retention. In 2014 I created a separate website for this purpose: CVRAIZ: Specifying The African Ethnic Origins for Cape Verdeans. In 2015 (on this blog) I published my first survey findings based on Cape Verdean personal DNA test results. Furthermore I have always been applying a comparative analysis to see how Cape Verde fits in the broader picture of the Afro-Diaspora.1

In the last couple of years several new peer reviewed studies have been published using a similar research approach. So that makes it very interesting to compare notes with my own research findings! I will mainly focus on the most recent study “The Admixture Histories of Cabo Verde” (Laurent et al., 2023) (original title prior to peer review). But I will also refer to a few other studies.

The Admixture Histories of Cabo Verde (Laurent et al., 2023)

____________________

“Cabo Verdean Kriolu is the first creole language of the TAST, born from contacts between the Portuguese language and a variety of African languages. The archipelago thus represents a unique opportunity to investigate, jointly, genetic and linguistic admixture histories and their interactions since the mid-15th century.” (Laurent et al., p.4).

“We find that admixture from continental Europe and Africa occurred first early during the TAST history, concomitantly with the successive settlement of each Cabo Verdean island between the 15th and the early 17th centuries”. (Laurent et al., p.26).

“Finally, we find that recent European and African admixture in Cabo Verde occurred mainly […] in the 1800s“. (Laurent et al., p.27).

“our results highlight both the unity and diversity of the genetic peopling and admixture histories of Cabo Verde islands […].” (Laurent et al., p.27)

____________________

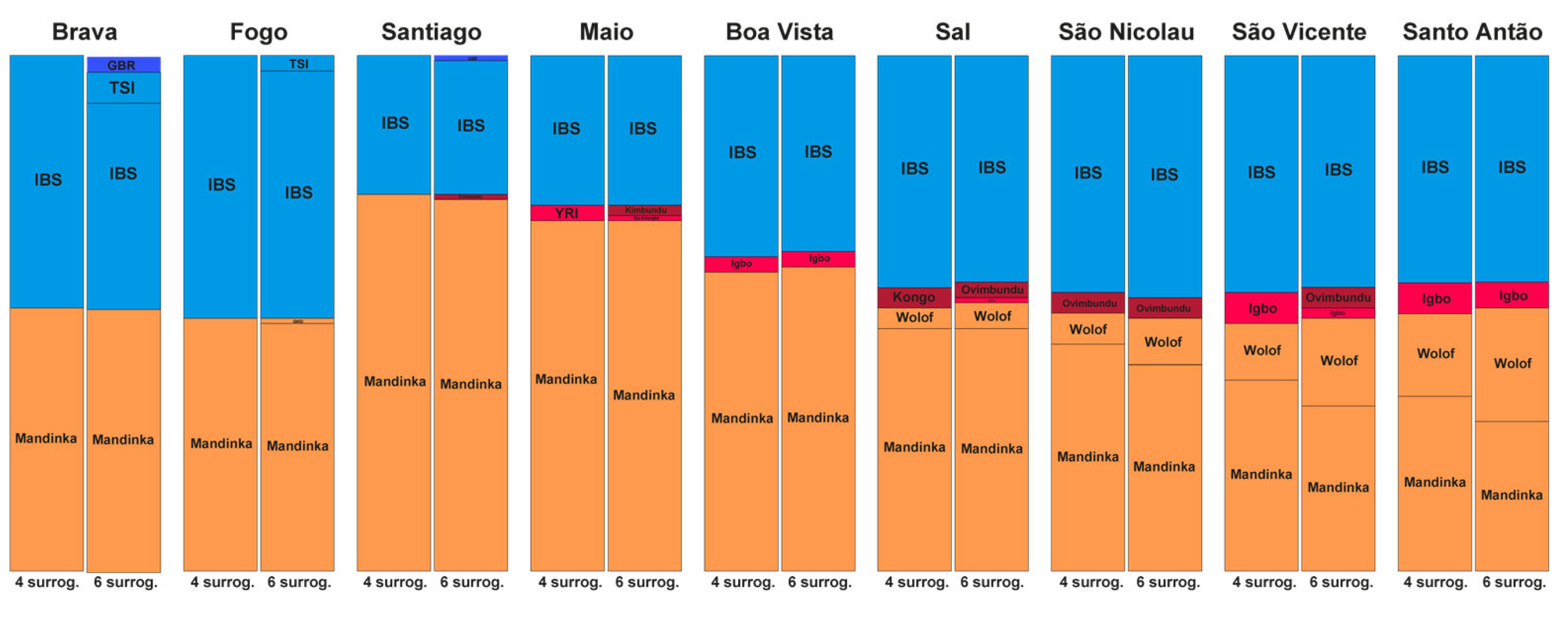

Figure 1 (click to enlarge) Source: Korunes et al. (2022). This plot shows how there’s shared ancestry between all islands. Even when the degrees of kinship will naturally be greater on each separate island and also among certain subsets of islands. In particular the socalled NW cluster (a.k.a. Barlavento islands) and Boavista. Fogo is being mentioned as having the highest incidence of endogamy. While this study also confirms that Santiago is clearly the oldest population of the entire island group. Based purely on their DNA analysis but in fact in line with known history!

Source: Korunes et al. (2022). This plot shows how there’s shared ancestry between all islands. Even when the degrees of kinship will naturally be greater on each separate island and also among certain subsets of islands. In particular the socalled NW cluster (a.k.a. Barlavento islands) and Boavista. Fogo is being mentioned as having the highest incidence of endogamy. While this study also confirms that Santiago is clearly the oldest population of the entire island group. Based purely on their DNA analysis but in fact in line with known history!

***

Recent studies on Cape Verdean Genetics

- A genetic and linguistic analysis of the admixture histories of the islands of Cabo Verde (Laurent et al., 2023).

- Sex-biased admixture and assortative mating shape genetic variation and influence demographic inference in admixed Cabo Verdeans (Korunes et al., 2022).

- Rapid adaptation to malaria facilitated by admixture in the human population of Cabo Verde (Hamid et al., 2021).

My own research

- 100 Cape Verdean AncestryDNA results (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

- DNA matches reported for 50 Cape Verdeans on AncestryDNA (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

- 100 Cape Verdean 23andme results (Fonte Felipe, 2021)

- Ethnic group matches on 23andme for 50 Cape Verdeans (Fonte Felipe, 2022)

***

I have been eagerly anticipating these most recent DNA studies on Cape Verdean genetics. And I am also very excited about the prospects for follow-up research. These new papers are firstmost a continuation of previous peer reviewed DNA studies about Cape Verde (see this link for an overview). In fact some outcomes repeat and reinforce my own earlier key findings (2011-2022).2 Still there are a few intriguing novelties as well. Providing meaningful insight.

I truly appreciate all the efforts of the research teams behind these studies. But I do have to point out that I have mixed feelings about the accuracy of the historical framework. Especially as provided by Laurent et al. (2023). This study seems to have overlooked an essential aspect of Cape Verde’s historical demography. Because most likely already in the late 1600’s a majority of the Cape Verdean population (both black and mixed-race) was no longer enslaved (see this table). Cape Verde is indeed part of the Atlantic Afro-Diaspora. And especially in its early history (1460-1660) Cape Verde was greatly impacted by the TAST (Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade). But several singular aspects about the Cape Verdean experience do require very careful and context-dependent analysis!

- Main outcomes

- Genetic clustering of Cape Verdeans according to island origins.

- Differentiation of African ancestry according to island origins.

- Greater genetic affinity with Wolof samples among Barlavento islanders

- Minor “Nigerian” and Central African lineage among Cape Verdeans

- Various admixture pulses but all islands have substantial shared ancestry from the 1500’s.

- Getting the historical context right

- Most Cape Verdeans (80+% of population) have been free of slavery since at least 1731

- Other points of critique.

- Suggestions for future research

- Sampling: apply criterium of 4 grandparents born on the same Cape Verdean island.

- More granular analysis of non-Senegambian/Iberian origins: Sierra Leone, Sephardi Jewish, Goa etc..

- New research agenda involving Cape Verdean Diaspora.

***

1) Main outcomes

Genetic clustering of Cape Verdeans according to island origins

Figure 1.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: Korunes et al. (2022). Notice how the NW cluster (Santo Antão, São Vicente, and São Nicolau) are grouped quite closely also with the Boavista samples. The Fogo and Santiago samples are further apart but do seem to form a separate Sotavento grouping or pairing. Which is in line with these islands having the oldest settled populations. The Barlavento populations appear to be mostly an offshoot. The European samples (IBS) are from Spain and the African samples (GWD) are from Gambia. Chosen for modeling purposes.

***

The three studies I listed above show a great deal of overlap in their general findings. Providing mutual corroboration and also consistent with my own research across the years. However only Laurent et al. (2023) provides new sampling. For the first time including samples from all 9 populated Cape Verdean islands! Including Brava, Maio and Sal (see Table 3.1). Most of the Santiago samples in this study are however from an earlier study from this research team (Verdu et al., 2017). The Cape Verdean dataset being used by Hamid et al. (2021) and Korunes et al. (2022) is taken from Beleza et al. (2012/2013). These older peer-reviewed studies have already been discussed in this blogpost (section 2).

Due to space constraints I am only highlighting two main outcomes further below. But in fact several fascinating topics are described in these new DNA studies. For example Hamid et al. (2021) provides an interesting (but speculative and incomplete!) take on why Santiago shows higher African admixture levels than other islands.3 Also in the two other studies so-called ROH (runs of homozygosity) is being investigated. Basically this type of analysis is based on shared IBD (Identical by Descent) segments and intended to clarify population structure. Which is certainly very useful! However these preliminary outcomes are unfortunately quite ambigious and open to multiple interpretation.

Furthermore Laurent et al. (2023) also provides an elaboration of their earlier research into how linguistics and genetics may correlate among Kriolu speakers in Cape Verde (see Verdu et al. 2017). I find this to be an extremely captivating research field. I personally think it is very striking to see both genetic and linguistic continuities between Barlavento and Sotavento islands, despite also some divergence. As they say in Cape Verde: Nos Tud Nos É Criol! Hopefully their intended follow-up efforts will be more in tune with the distinct island specific varities of Kriolu. See also discussion in section 3.

Eventhough these studies are focusing on Cape Verde I do think they have plenty of added value for other Afro-descendants as well. Because the methods being used to analyze admixture patterns, timing of admixture, ethnogenesis, identification of specific African lineage, impact of TAST etc. are also highly relevant for other parts of the Afro-Diaspora. In fact, despite its small size Cape Verde is often used by researchers as an illustrative case study with wider implications. In particular because of Cape Verde’s early involvement with TAST but also because of its relatively homogenous origins within Africa (Upper Guinea).

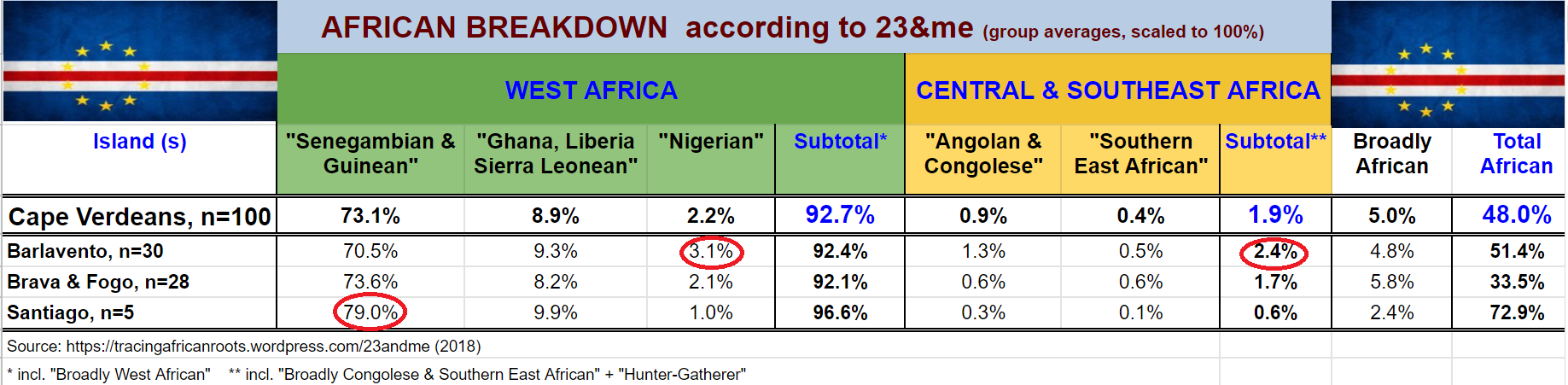

Differentiation of African ancestry according to island origins

Figure 1.2 (click to enlarge)

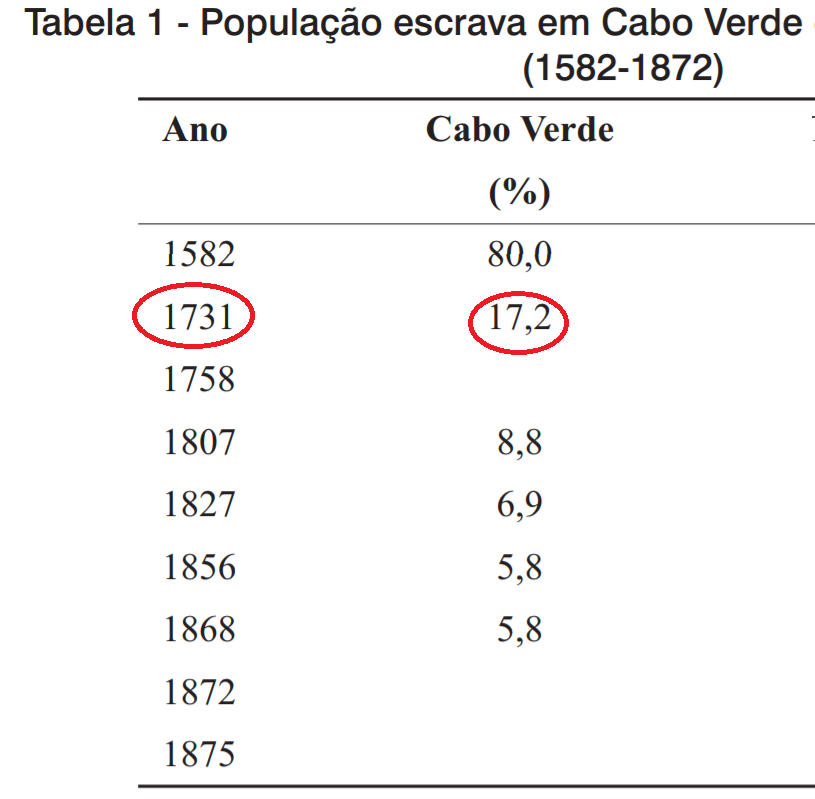

Source: Laurent et al. (2023). This chart is depicting 2 modeling outcomes for each island whereby their total ancestry is assumed to consist out of resp. 4 or 6 possible source surrogate populations. Overall speaking the best fitting African population are the Mandinka samples from Gambia. But intriguingly the African breakdown of the Barlavento islands (on the right) is more diverse. Not only additional Wolof is shown but also (in red/pink) minor shares of Nigerian (Igbo, YRI= Yoruba) and Central African admixture (Kimbundu, Kongo, Ovimbundu). IBS is a proxy for Iberian (Portuguese) DNA, GBR is a proxy for British DNA and TSI is a proxy for Italian DNA. See this link for a complete overview of the possible source populations being used to generate this chart.

Source: Laurent et al. (2023). This chart is depicting 2 modeling outcomes for each island whereby their total ancestry is assumed to consist out of resp. 4 or 6 possible source surrogate populations. Overall speaking the best fitting African population are the Mandinka samples from Gambia. But intriguingly the African breakdown of the Barlavento islands (on the right) is more diverse. Not only additional Wolof is shown but also (in red/pink) minor shares of Nigerian (Igbo, YRI= Yoruba) and Central African admixture (Kimbundu, Kongo, Ovimbundu). IBS is a proxy for Iberian (Portuguese) DNA, GBR is a proxy for British DNA and TSI is a proxy for Italian DNA. See this link for a complete overview of the possible source populations being used to generate this chart.

***

Greater genetic affinity with Wolof samples among Barlavento islanders

____________________

” Furthermore, we find that all Cabo Verdeans almost exclusively share African haplotypic ancestries with two Senegambian populations (Mandinka and Wolof) and very reduced to no shared ancestries with other regions of Africa.

More specifically, we find that the Mandinka from Senegal are virtually the sole African population to share haplotypic ancestry with Cabo Verdeans born on Brava, Fogo,Santiago, Maio, and Boa Vista, and the majority of the African shared ancestry for Sal, São Nicolau, São Vicente, and Santo Antão. In individuals from these four latter islands, we find shared haplotypic ancestry with the Wolof population ranging from 4%–5% for individuals born on Sal (considering four or six possible sources, respectively), up to 16–22% for Santo Antão.“ (Laurent et al., 2023, p.9)

____________________

The results shown above are potentially very insightful! However you should also be aware of the various limitations which are tied to this sort of analysis.4 I will first discuss the findings of greater genetic affinity with Wolof samples among Barlavento islanders, especially Santo Antão. Which presumably might be connected with founding effects! I will then proceed with the minor Nigerian and Central African findings. Again very intriguing and showing differentation across the islands. But this is not a novelty. Because I myself have described this phenomenon in various blogposts since 2015 (see foot note 2).

I have been waiting for a long time to see Wolof samples being compared with Cape Verdean samples for genetic affinity. So I am very pleased that Laurent et al. (2023) performed this type of admixture analysis. But as always careful interpretation is a must! Given that it is practically impossible that Wolof ancestry does not exist for Santiago and Fogo as well. Plentiful historical records as well as linguistic evidence provide solid indications of an early Wolof presence in these foundational islands. Most likely the Wolof were forming a majority even in the first century of settlement (1460-1560). And hence they were decisive for Cape Verdean ethnogenesis in all islands ultimately!

On first sight the outcomes seem to be suggesting a shift in the composition of Upper Guinean roots when comparing people from the Barlavento islands with Sotavento islands. It is indeed remarkable that people from Santiago, Fogo but also neighbouring Brava and Maio are exclusively showing Mandinka as best fitting Senegambian population. While Wolof affinity seems to increase on a gradient among Barlavento islanders. Peaking for the western-most island of Santo Antão (see this map).

I actually have a strong hunch this outcome is firstmost reflecting a modeling issue/artefact. Still I am curious to know how this might relate to these old statements of mine from 2014:

____________________

“[Wolof:] Pending on future DNA research founding effects might be substantial. Therefore most widely spread among all segments of Cape Verdean population?“(Fonte Felipe, 2014)

“So we can assume that for a majority of Cape Verdeans the African part of their ethnogenesis dates mostly from the period before 1731 at the very least and most likely especially the 1500’s playing a crucial part. […]

For a subset of Cape Verde’s population there was still continued African geneflow also in the 1700’s and 1800’s leading perhaps to some differentiation in African ethnic origins between islands as well as socially defined subgroups on the same island.”

“could mean that the mulattos or mestiços from the census might have “timecapsuled” the African part of their mixed ancestry dating from the 1400’s-1600’s more so than freed blacks/forros. Many of these mixed people would later on be prominent among those sent out to to settle the islands of the north in the late 1600’s/1700’s” (Fonte Felipe, 2014)

____________________

More follow-up research is needed to see how robust this finding from Laurent et al. (2023) might turn out to be. Again by default this type of analysis leads to simplified results. Because after all their modelling is set up in such a way that only 4 or 6 source populations are taken into consideration. I suppose more granularity could be obtained by further expansion of the Senegambian reference panel.

But I was surprised that apparently there was no genetic affinity found with the Fula and Jola samples which were already being used. Perhaps that’s a telling sign of so-called over-smoothing. Whereby similar types of DNA get grouped in 1 lump category because it has a greater pull (mostly Mandinka in this case). Because again there is practically no way that Cape Verdeans would not have any meaningful ancestral connections with the Fula or Jola people (from Casamance)! [It appears the Fula samples were removed from further analysis. Which is the reason they are not considered as a source candidate in figure 1.2, see also this very helpful reply in the comment section]

Even more importantly I think another approach is required. In particular the more commonly used analysis of shared IBD segments. Strongly indicative of recent ancestry, when reaching a certain threshold. This kind of IBD analysis is actually also the basis for the genetic groups being reported on 23andme.

***

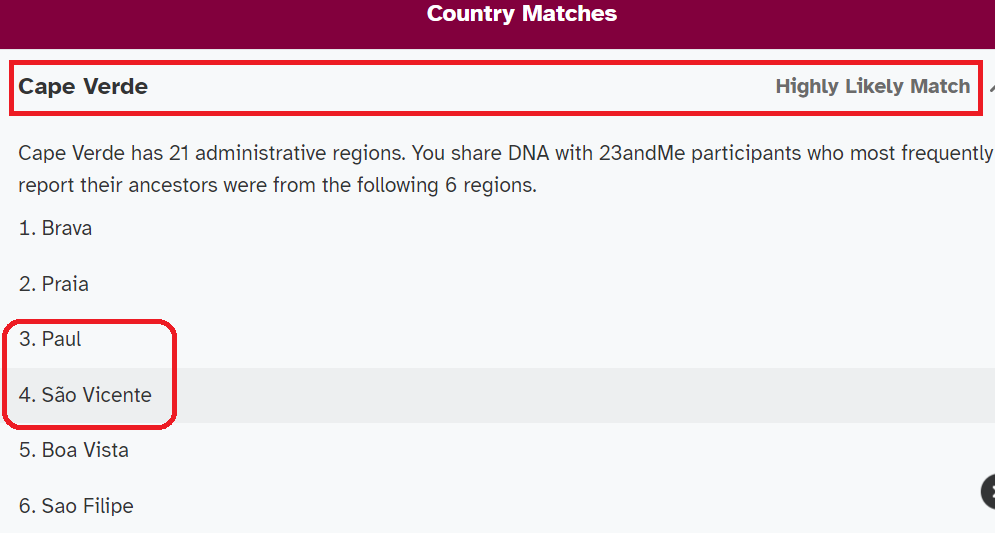

Genetic groups on 23andme for a Cape Verdean

Figure 1.3 (click to enlarge)

Source: 23andme. This screenshot features the so-called genetic group results of a Cape Verdean. Realistically speaking practically all Cape Verdeans should have both Mandinga and Fula/Wolof lineage, due to endogamy and shared African roots. In fact the “Senegambian & Guinean” ancestors of this person and other Cape Verdeans should also include other additional ethnic origins as well. Such as Sereer, Balanta, Jola etc.. Just because these groups are undetected or not covered yet by 23andme’s database doesn’t mean it couldn’t be there!

***

This strong genetic affinity for Cape Verdeans with both Mandinka and Wolof samples was actually already noticeable on 23andme since 2022. I did a survey then among 50 Cape Verdeans who tested with 23andme and received this update. And a almost equal number of them was assigned to either the genetic group of “Mandinka” (14/50) or “Fula and Wolof” (13/50), see this chart. There were no other genetic groups being reported from mainland Africa. See also this blogpost:

- Ethnic group matches on 23andme for 50 Cape Verdeans (Fonte Felipe, 2022)

Also in 2018 I performed a survey among 50 Cape Verdeans who tested with Ancestry to investigate their DNA matches from mainland Africa. And in this case it turned out that actually Fula DNA matches were most frequent for Cape Verdean Ancestry customers. See this blogpost:

- DNA matches reported for 50 Cape Verdeans on AncestryDNA (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

All combined these are very valuable indications to learn more about the specific Upper Guinean origins of Cape Verdeans! Arguably I would say that the results based on IBD matching are on more solid ground than the findings of Laurent et al. (2023). But nothing conclusive yet! The following disclaimers still need to be kept in mind.

____________________

“To be kept in mind is that this does not say anything per se about the overall proportion of this “Fula & Wolof” or “Mandinka” lineage. Further research is needed to establish how much African lineage for Cape Verdeans is tracing back to earlier centuries and also from other ethnic groups (such as Papel, Biafada, Jola etc.). Because right now such lineage is undetected by 23andme’s matching algorithm and not covered by 23andme’s database.” (Fonte Felipe, 2022)

“frequency of DNA matches from a certain place/ethnic group may not always correlate with autosomal contribution, proportionally speaking. In other words just because my Cape Verdean survey participants seem to be extra “matchy” with Fula people does not right away imply that the Fula represent the biggest ancestral component for Cape Verdeans.

Although arguably already a case can be made that Fula ancestry from especially the late 1700’s and 1800’s among Cape Verdeans has been very considerable. As in fact this may also be corroborated by historical evidence. However earlier lineage from different ethnic groups may very well not be showing up in adequate proportions yet. When relying only on DNA matching patterns.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

____________________

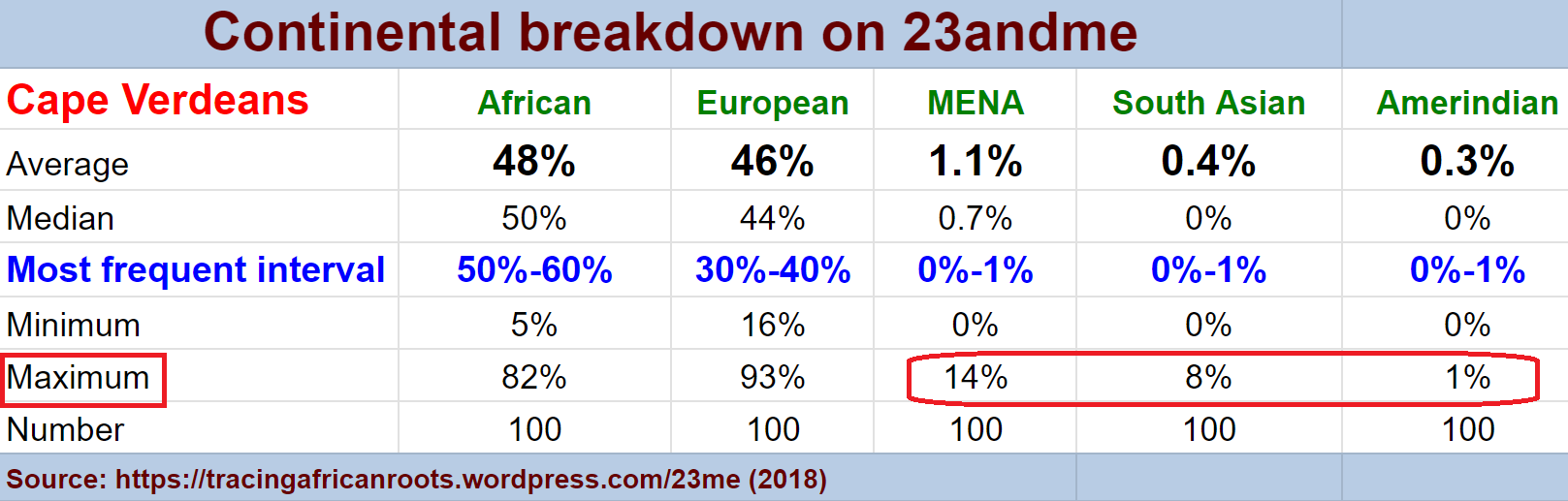

Minor “Nigerian” and Central African lineage among Cape Verdeans

Figure 1.4 (click to enlarge)

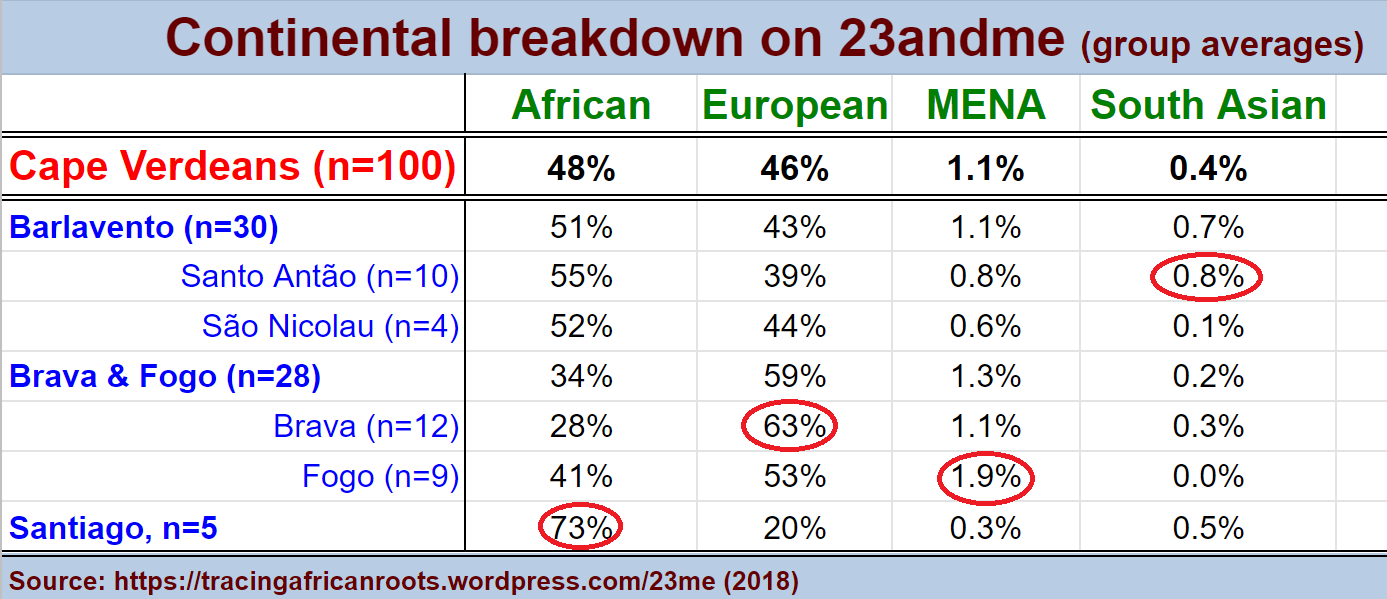

Source: my survey findings for 100 Cape Verdean 23andme results (2021). Notice the subgroup averages of 3.1% “Nigerian” and 2.4% “Central & Southeast African” for Barlavento. Somewhat higher than for other subgroups. However such minor scores are sometimes also found for Brava, Fogo and Santiago.

***

____________________

“Finally, we find limited (1–6%) shared haplotypic ancestry with East Western […] or South-West Central […] African populations in all Cabo Verdean islands, except Fogo and Brava, and the specific populations identified and their relative proportions of shared haplotypic ancestries vary across analyses.” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.9)

This potentially indicates differences in shared ancestries with different continental African populations across islands in Cabo Verde, which remains to be formally tested.” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.8)

____________________

The quotation above is referring to another very interesting finding from Laurent et al (2023). All the more so because it corroborates my own research findings from 2015, 2018 and 2021. As can be seen in figure 1.2 this new study shows a minor yet clearly detactable genetic affinity between their Cape Verdean dataset and their samples from the eastern part of West Africa (“East Western Africa” = Lower Guinea). Especially Igbo ones from Nigeria. While also their (southwest) Central African samples (Kongo, Ovimbundu and Kimbundu) seemed to show shared ancestry in some cases. Especially for Barlavento islands but to a lesser degree also Maio and Santiago.

When I first discovered this occurence of unexpected non-Upper Guinean lineage in 2015 I was naturally very cautious. Because afterall admixture analysis has several limitations. Furthermore this is unexpected when going by Cape Verde’s geography and known history. Documented sources clearly describe the area in between Senegal and Sierra Leone (Upper Guinea) as practically the only provenance zone for African captives brought to Cape Verde safe for some individuals who came on atypical slave voyages from further away.5 See also this link.

However these minor Lower Guinean and Central African scores keep coming up for Cape Verdeans when they do personal DNA testing. Even after several updates on both Ancestry and 23andme. I myself currently show 2% “Nigeria” on Ancestry and 2.7% “Nigerian” on 23andme. So to be sure this still represents a small proportion of the African genepool for Cape Verdeans. But certainly worthy of follow-up investigation!

This is something I have actually already done in 2018. Which is why I am inclined to say that in many cases even trace-amounts of Central African or “Nigerian” DNA might be the “real deal” for Cape Verdeans. Having these additional findings from Laurent et al (2023) makes for an even stronger case that this could be true. I have explored the various possibilities already to a great extent in previous blog posts. So for further discussion see:

- “Southeast Bantu”, artefact or genuine? (scroll down to section 5)

- Beyond Upper Guinea: valid outcomes or misreading by AncestryDNA? (scroll down to section 4)

- Regional admixture as corroboration for African matches outside of Upper Guinea? (scroll down to section 4)

- Substructure within Cape Verde (scroll down to section 2)

____________________

“Follow-up research focusing on associated DNA matches as well as dedicated family tree research may clarify things in individual cases. While possibly also a locally specific historical context may apply for the Barlavento islands. In particular in regards to (slightly) deviating slave trade patterns when compared with Santiago, the main hub of slave trade with Upper Guinea. Perhaps occasionally involving contraband Northwest European traders?” (Fonte Felipe, 2021).

“such scores (when truly genuine) might either be due to African captives outside of the expected Upper Guinea area being present (sporadically) in Cape Verde during the Slave Trade period. Or otherwise also caused by family histories involving back & forth migrations to and from Angola, Brazil, São Tomé & Principe and Mozambique. All fellow ex-Portuguese colonies. This latter scenario will usually be easier to investigate of course.” (Fonte Felipe, 2021).

____________________

Most admixture dates back from 1500’s?

____________________

“The dating of the socalled Creolization process/transition is fundamental for tracing back African ethnic roots“. (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

“Tracing back from Creole to African is going to take you back several centuries and many generations therefore. Everyone has individual family trees (I will continue stressing this) however generally speaking for many Cape Verdeans it might mean that most of their African mainland born ancestors arrived in Cape Verde more than 400 years ago […]”. (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

____________________

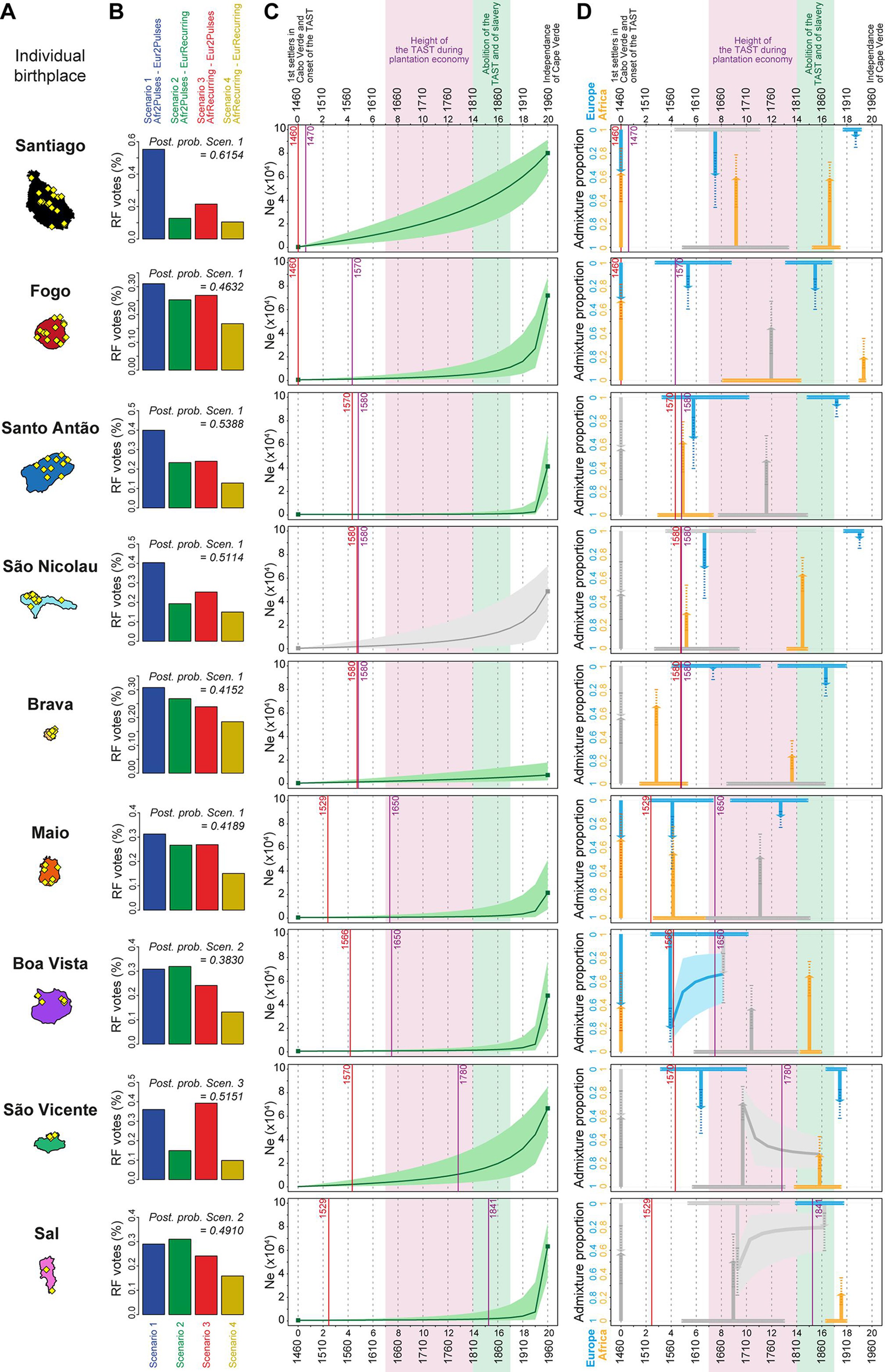

Figure 1.5 (click to enlarge)

Source: Korunes et al. (2020). This overview is taken from a very useful one-page summary of a presentation given during a genetics conference: Assortative mating and rapid adaptation shape genetic variation in admixed Cape Verdeans.

____________________

“This observation, together with IBD and kinship patterns, support the serial founding of the groups of islands as the main model of settlement of Cabo Verde, as opposed to their independent settling as some historical data suggest (Correia e Silva 2002). This type of serial founding scenario is common throughout recent human migration, underscoring that settlement patterns, in addition to settlement timing, are critical components of accurately inferring human demographic history.” (Korunes et al., p.12).

____________________

***

Figure 1.6 (click to enlarge)

Source: Laurent et al. (2023). This overview is quite extensive. See this explanatory note from the study for more understanding. Looking into panel D (on the right side) is probably most useful. It highlights for each island the predicted timeperiods of both African (yellow) and European (blue) geneflow. Panel C should not be misconstrued. Because it is depicting a model-based reproductive population size and is not based on actual historically known population numbers!

____________________

“[…] scenario-choices indicate that multiple pulses of admixture from the European and African source populations (after the founding admixture pulse, two independent admixture pulses from both Africa and Europe […]: Scenario1), best explain the genetic history of individuals born on six of nine Cabo Verdean islands. Furthermore, we find that even more complex scenarios involving a period of recurring admixture from either source best explain the history of the remaining three islands.” (Laurent et al., p.19)

____________________

The main take-away from above quotations and charts would be that across the Cape Verdean islands a substantial component of shared ancestry can be detected. Most likely dating back to foundational admixture events taking place during the 1500’s on both Santiago and Fogo, the earliest populated islands. Greatly indicative of a “stepping stone” settlement of the islands. This outcome was actually already established in an earlier paper (Beleza et al., 2012). However back then the analysis was based solely on Y-DNA (male haplogroups). While this time genomewide autosomal DNA markers are being used.

At the same time Laurent et al. (2023) does also identify additional geneflow for each island, especially during the 1800’s. Which would be indicative of differentiation among (subsets) of the islands, at least to some degree. This has a profound impact for Cape Verdeans who have done personal DNA testing. Because it will determine their DNA matching patterns to a great extent. First of all when looking at close DNA relatives and their Cape Verdean island origins. These will usually closely mirror the cluster patterns shown in figure 1.1. As long as your family origins only involve 1 island or neighbouring islands.

But also the odds of finding mainland African as well as Portuguese DNA matches will naturally be highest when relating to the most recent timeperiods (1800’s). Often indicated by fitting genetic groups/country matches on 23andme and to a much lesser extent also by Ancestry’s tool of DNA communities.6 However this could possibly still be obscuring any earlier links with African and European heritage dating from the 1500’s/1600’s. As well as any unrecorded earliest island origins from either Fogo and/or Santiago for Barlavento islanders. Because due to dilution these connections will often remain undetected. See also this blogpost series (part 2 is still to be written).

Finding the approximate time period(s) when your mainland African ancestors arrived in Cape Verde is crucial for Tracing African Roots. This is something I have always said from the start on this blog and also on my CVRAIZ website. So these new estimates for the timing of African and also European geneflow are potentially very significant! On the other hand much more research is needed. This type of analysis is not intended to be 100% accurate but rather indicative. The outcomes as displayed in figures 1.5 and 1.6 are heavily dependent on underlying assumptions and other inherent limitations of statistical modelling. This much is also explained within the studies.7

***

Ancestry Timeline on 23andme for a Cape Verdean

Figure 1.7 (click to enlarge)

Source: 23andme. This screenshot features the Ancestry Timeline results for a Cape Verdean who has done extensive family tree research (into the 1700’s). He is indeed aware of (several) Portuguese ancestors within the estimated time frame of 1760 and 1850. But he does not know of any mainland African ancestors (yet). It is theoretically possible he might also have one or a few mainland African ancestors from the 1800’s. But generally speaking most of his Senegambian/Guinean ancestry should date back from much earlier. Just like for almost all other Cape Verdeans.

***

On 23andme there is a similar tool to learn more about when approximately a particular ancestry entered your family tree. This is called Ancestry Timeline. Sometimes the estimates given are quite useful but other times they are completely off. Again mostly due to inherent modeling issues and assumptions not always being relevant. This is why I always recommend to judge plausibility by contrasting with the actual known historical context, personal genealogy as well as any other relevant clues.

In fact within Laurent et al. (2023) there is an extensive discussion of the admixture scenario’s per island, see appendix 5. They also provide a useful Excelfile which contains demographic information/dates which were used for their modeling efforts. However again a word of caution: the authors of these studies are not trained historians! The historical data they are using is incomplete. By default I would say, but actually I am also missing some important sources. Furthermore their interpretation of key aspects of Cape Verdean demography is sometimes questionable or even inaccurate. Further discussion in the next section of this blog post.

- Historical Demography of Cape Verde (Fonte Felipe, 2014)

- Appendix 5: Genetic admixture histories of each Cabo Verdean island of birth (Laurent et al., 2023).

- Historical landmark chronology for the peopling history of Cabo Verde. (Laurent et al., 2023).

2) Getting the historical context right

Bottomline of this section is that incomplete knowledge of Cape Verde’s history can result in exaggerated expectations of the genetic and social impact of Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (TAST). However not everything about Cape Verde is TAST related! A lack of much needed nuance leads to an overly deterministic interpretation within especially Laurent et al. (2023).

____________________

“Be careful to respect the localized context and different historical trajectories across the Afro-Diaspora. Instead of just letting one single perspective on inter-racial relationships overcloud things. This goes especially for Cape Verdeans who despite being part of the Afro-Diaspora in many aspects have a unique history of their own. And as a consequence their family trees & genealogy will usually not fit in well with simplistic generalizations. And even less so with ideologically charged assumptions arising from a specific USA context or an overly Americanized mindset.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

“For Cape Verdeans it is vital to be aware that despite being the earliest hub of Trans-Atlantic Slavery in the 1500’s Cape Verde was actually also one of the first creolized societies in the Atlantic world! In fact the economic importance of slave trade quickly declined after the 1600’s because other slave ports on the mainland became more significant. Due to both racial mixing and a greatly diminished need of slave imports Cape Verde had a locally born population with a clear majority consisting of free-status Afro-descendants already in the early 1700’s (as confirmed by the 1731 census)!

Slavery did continue up till 1878 for a minor part of the population. However the resulting gene flow from mainland Africa must have been much more subdued in later time periods, on average. Given that the enslaved portion of Cape Verde’s population was […] below 20% throughout the 1700’s. This implies that generally speaking when tracing back to mainland Africa Cape Verdeans will often have to go back to the 1500’s and/or 1600’s instead of the 1700’s/1800’s as is more usual among Trans-Atlantic Afro-Diasporans.” (Fonte Felipe, 2021)

____________________

References for Cape Verdean Demographics & History. Not meant to be exhaustive but check this overview:

-

- Bibliography of Cape Verdean History (Lire CapVert, in French but VERY thorough!)

- CVRAIZ: Specifying The African Ethnic Origins for Cape Verdeans (Fonte Felipe, 2014)

For those who understand Portuguese this RTP documentary series is highly recommended viewing! It is focused on explaining the early settlement history of Cape Verde. In particular the island of Santiago and Ribeira Grande/Cidade Velha. But it also deals with how the Barlavento islands were increasingly settled in the 1600’s/1700’s by people with freed status from both Fogo and Santiago. Fleeing recurring droughts, in search of new farming land but also a less oppressive social regime. The first episode is with a Portuguese archaeologist. The second and third episode feature well known Cape Verdean historian Antonio Correia e Silva.

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade voyages departing from Cape Verde

Table 2.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (2020) Cape Verde was the first main Trans-Atlantic slaving entrepot. Almost 75% of Cape Verde’s slave trade was carried out during the 1500’s. After a steep decline of slave trading activities in the 1600’s/1700’s Cape Verde was dragged back into the “odious commerce” again in the early 1800’s. However proportionally speaking this was quite minor when compared to the 1500’s. See this link for underlying numbers.

***

The new DNA studies reviewed in this blogpost are all making explicit reference to Cape Verde’s demographic history.8 Which is indeed essential in order to understand most of their findings. However especially Laurent et al. (2023) do not seem to have fully grasped a few singular aspects about the Cape Verdean experience when compared with other parts of the Atlantic Afro-Diaspora. Undoubtedly the TAST had a major impact on Cape Verde’s genepool.9 However it seems to be overlooked that Cape Verde’s function as a main slave trading platform ended during the 1600’s. This can easily be confirmed from the authoritative Slave Voyages database (see Table 2.1).10

Naturally this section is just meant as constructive criticism. Because to repeat myself Laurent et al. (2023) does provide valuable insight and is also in many ways in agreement with my own ongoing research. Offering plausible outcomes when looking at the relevant context and the relevant statistics. However in the interest of countering any possible “post-truth” tendencies I feel obliged to point out that statements below are misinformed or just downright inaccurate.11 Again especially for the time framing. Because slave trading activities in Cape Verde did indeed continue after the 1600’s up into the 1800’s. But clearly with a much lesser intensity and most likely also with lesser genetic effects than during the peak period of the 1500’s.

____________________

“Cabo Verde, the earliest European colony of the era in Africa, a major Slave-Trade platform between the 16th and 19th centuries” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.1).

“After 1492, and in particular after the 17th century expansion of the plantation economy in the Americas, Cabo Verde served as a major slave-trade platform between continents.” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.4).

“Thus, our results highlight that the strong and recurrent demographic migrations of enslaved Africans brought to Santiago during the second half of the TAST do not seem to have left a similar genetic admixture signature.” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.69).

____________________

Whenever I read genetic studies I always pay close attention to how the authors attempt to contextualize or explain their main research findings. As I find that historical aspects often tend to be oversimplified or even misrepresented. Given that the authors of genetic studies are usually mathematically trained naturally they tend to be focused rather on the technical aspects of whatever it is they are researching.12 However genetics is embedded in the social sciences as well. Especially the history of population migrations.

This misunderstanding on part of the authors of Laurent et al. (2023) surely was not intentional. However it does seem to have affected their expectations in advance. Especially about mainland African geneflow being “regular” during “most of Cabo Verde history” (Laurent et al., p.26). This was clearly not the case which fortunately their admixture analysis did also demonstrate. Because as discussed in the previous section they found that the main admixture pulses took place in the 1500’s and 1800’s (“after the abolition of the TAST and of Slavery“). Unlike many other parts of the Afro-Diaspora. Which again should not have been a surprise if this Cape Verde-specific context had been clarified in a proper way.

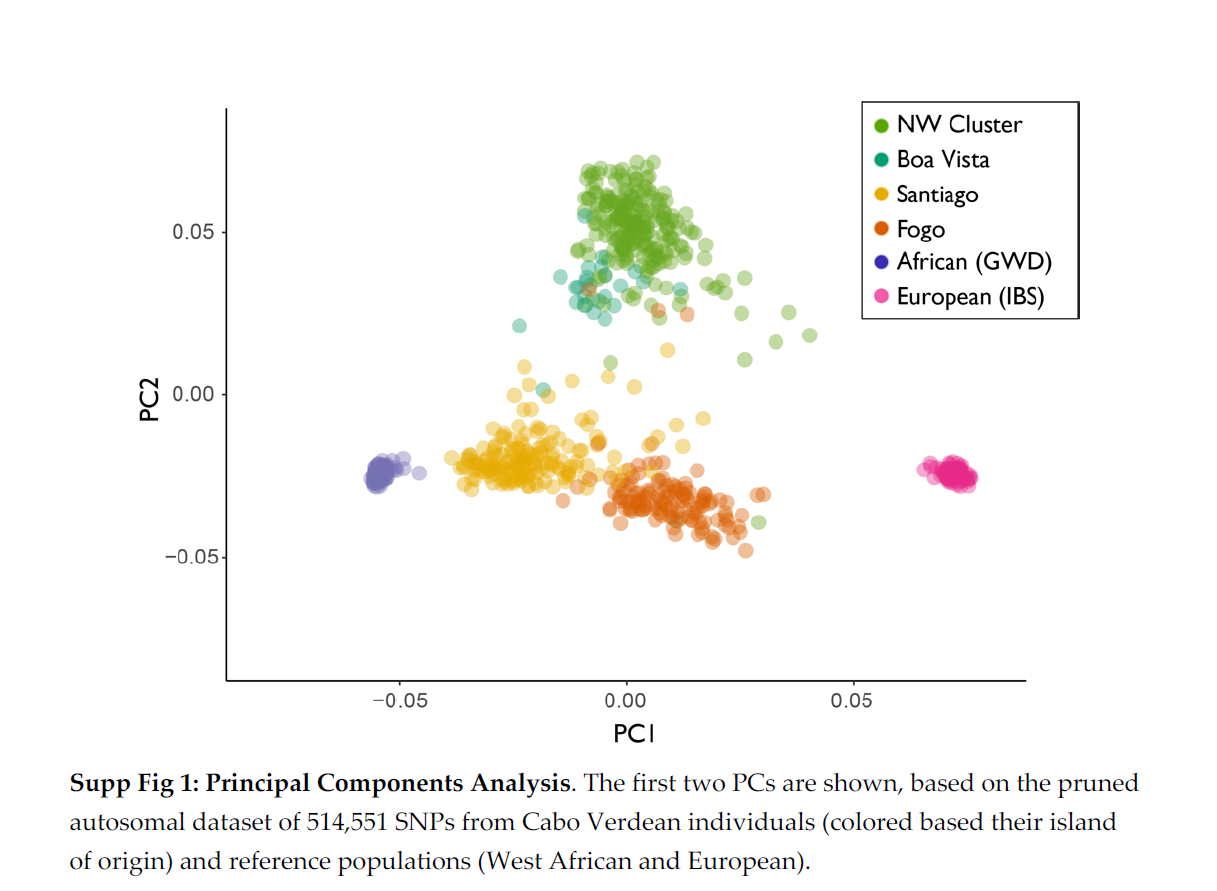

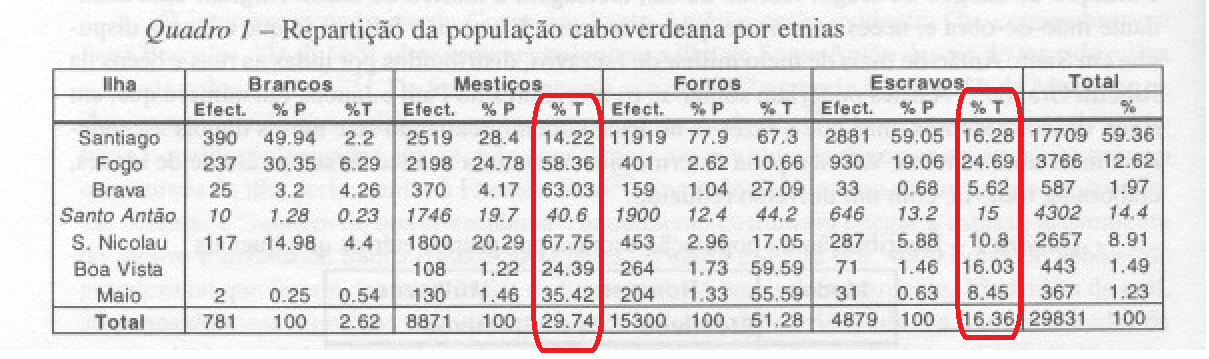

Most Cape Verdeans (>80%) have been free of slavery since at least 1731

Table 2.2 (click to enlarge)

Source: G. Seibert (2014). This chart shows the proportion of enslaved people living in Cape Verde. Take notice that in 1731 more than 80% of Cape Verdeans had freed status. In fact probably already in the late 1600’s, although we do not have any census records for that period. Slavery did remain a reality for many people still but overall speaking they were a small minority of Cape Verde’s total population, less than 10% during the 1800’s. This provides a stark contrast with most other parts of the Afro-Diaspora.

***

1731 census details for each island

Table 2.3 (click to enlarge)

Source: Santo Antão de Cabo Verde (1724-1732) da ocupação inglesa a criação do regime municipal, A.T. de Matos (1997). Brancos = whites; Mestiços = mixed-race; Forros = people with freed status; Escravos = enslaved people. Column “Efect” = absolute numbers. Column “% P” = relative share of each island within overall total for each sub-category. Column “% T” displays the relative share within each island. It adds up to 100% from left to right. Notice that the island averages for enslaved people range from 5% in Brava to almost 25% in Fogo. Island averages for mixed race people range from 14% in Santiago to 67% in São Nicolau.

***

The information displayed in the tables above also seems to not have been available or fully grasped by Laurent et al. (2023). The data really speaks for itself. And it can be deduced already that TAST related African geneflow after the late 1600’s must have been subdued. Given that only a relatively small share of the entire population remained enslaved. And TAST voyages departing from Cape Verde drastically decreased during the 1600’s (see Table 2.1). So we can assume that for a majority of Cape Verdeans the African part of their ethnogenesis dates mostly from the period before 1731 at the very least and most likely especially the 1500’s playing a crucial part. Based also on additional clues. Such as most enslaved persons being born in Cape Verde itself (see this blog post).

Looking more closely into Table 2.3 it can be confirmed that this goes for each island. Including Santiago which even shows a lower share of enslavement (16.28%) than Fogo (24,69%)! This corresponds with what various historians have been saying: Cape Verde did not have a classical plantation economy during the 1700’s and 1800’s. It can also clearly not be typified as a classical slave society. Even when during the 1500’s it was very instrumental in providing the blueprint of such societies. However during the 1600’s and onwards this model became much more prevalent throughout the Carribean and the Americas.

Instead Cape Verde became a so-called “society with slaves”. The greater majority of its population being self-sustaining peasants.13 To be sure pockets of the formerly dominant plantation economy (mostly cotton but also panos/textiles) did survive. Especially in Fogo and to a lesser degree in Santiago. Also salt mining in Boavista, Sal and Maio depended on enslaved labour. But these latter islands were insignificant populationwise. Also according to the 1856 census a big part of slave labour was actually being used for domestic help. This transformation which took place during the 1600’s occurred for various reasons. Cape Verde’s Sahelian climate being an important factor. For more details see the references for Cape Verdean Demographics & History given above.

***

Table 2.4 (click to enlarge)

Source: see directly above. This table is showing the racial composition of Cape Verde’s population (Branco=White; Mestiço=Mulatto; Negro=Black). Plus it also makes a distinction between enslaved black people (escravos) and black people with freed status (livres a.k.a. forro). Take note that the share of mixed people only reached a majority of the population in 1900!

***

Another seemingly misunderstood aspect is the gradually increasing share of mixed-race people in the Cape Verdean population. From Table 2.3 it can already be confirmed that on most islands in 1731 mixed-race people formed atleast 40% of the population. Aside from Santiago, Maio and Boavista. The plausible admixture events took place during the 1500’s/1600’s. As also indicated by the new DNA studies featured in this post.

This mixed-race segment within the overall Cape Verdean population would grow even more during the 1800’s and early 1900’s (see Table 2.4). Implying additional European geneflow during the 1800’s and late 1700’s. Which again appears to be confirmed by the findings of Laurent et al. (2023). However the consistent and exaggarated linking with TAST within Laurent et al. (2023) is distorting a proper understanding of how the Cape Verdean population came to be.14

____________________

“ongoing European geneflow taking place in the 1700’s & 1800’s would most likely not have involved unions with enslaved (mainland) African women at least not for the most part. But rather unions between in particular Portuguese men (probably especially exiled convicts or otherwise officials and seamen) and Cape Verdean women (either black or mixed) who usually might have hailed from families with freed status dating from several generations ago.

No doubt given the colonial context some structural element of power imbalance (beyond gender) would still have been at play. Although individual agency (incl. by females) is also not to be ruled out. Either way such a scenario does differ from the circumstances in many other parts of the Afro-Diaspora at the same time.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018).

“Either way more research needs to be done to establish in which time period European geneflow might have had the most impact on Cape Verdean genetics. As always I believe that a multi-disciplinary approach may deliver the best results instead of relying on one-sided and preconceived notions. Including a good grasp on local history, personal genealogy as well as DNA testing, not only in regards to admixture analysis and haplogroups but also in particular IBD matches.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018).

____________________

For further discussion see:

- Admixture mostly occurring in the 1500’s/1600’s or rather in the 1700’s/1800’s? (scroll down to section 2)(Fonte Felipe, 2018)

- Cape Verde Slave Census of 1856 (part 1) (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

- Cape Verde Slave Census of 1856 (part 2) (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

Other points of critique

____________________

“Overall, the paper is of interest to the field of human evolutionary genetics – that not only does it tell the story of a historically important population, but also the methodology behind this paper sets a great example for future research to study genetic and sociocultural transformations under the same framework“

____________________

- Evaluation of Laurent et al. (2023) by peer reviewers

- Evaluation of Laurent et al. (2023) by public reviewers

The quote above is a statement from one of the public reviewers of Laurent et al. (2023). I was actually also intending to send them my review notes when the paper was still in pre-print. But regrettably I was not able to do so in time. As already described above my main concern with this paper are the inaccuracies in how they describe the expected genetic and social impact of TAST for Cape Verde. The peer reviewers of Laurent et al. (2023) did also provide constructive critique. But I did not see this aspect being mentioned. Frankly I find that their flawed historical framework should not be copied by any other research teams who might take this paper as a basis for similar investigations regarding Cape Verde or other parts of the Afro-Diaspora.11

***

The Dragoeiro tree is one of the most distinctive tree species in Cape Verde. Only found on the Atlantic islands but not in the Americas. A nice reminder that researchers should always be aware of singular aspects and local contexts.

***

Again I have to emphasize I do think these new DNA studies offer great insights. Which is also exactly the reason I am sharing their main findings in this blogpost. Because I know for the casual reader it’s not always easy to see the forest through the trees of seemingly endless mathematical modelling and fancy graphics 😉 .15 Actually there are also a few other additional things which in my opinion could help to improve future DNA studies in this field. And also widen their readership among potentially many other interested people seeking to Trace African Roots!

- “All models are wrong, but some are useful”. This is a common warning against the unavoidable abstractions made by mathematical modelling. I certainly believe that especially the new approaches to infer the timing of admixture hold great promise. And in fact they are already providing good insights! However generally speaking I do think that DNA studies should be a means to an end and not the other way around.

- Outdated methodologies should preferably be disregarded. And “best practice” should prevail. However generally speaking what I notice is that the tools and techniques applied by some personal DNA testing companies often lead to more robust/detailed results than what is offered in DNA studies. Especially 23andme and Ancestry provide more adequate analysis for regional admixture and IBD matching patterns. At least in my opinion and based on my numerous survey results (see footnote 2). Obviously not without any shortcomings 😉 But I do suspect that due to source snobbery personal DNA testing results are not always fully appreciated for their informational value.

- In line with the peer reviewers I find that there is a lack of meaningful discussion on how the new DNA studies fit in with previous research. Integration or synthesis of knowledge is naturally very useful for everyone interested in these topics! I was hoping for more elaborate discussion especially regarding any overlap or progress being made regarding the pioneering study of Beleza et al. (2012). I was also missing a recognition of the work done by Stefflova et al. (2011): Dissecting the Within-Africa Ancestry of Populations of African Descent in the Americas. Although based on maternal haplogroups it does also feature a relevant comparison with samples from Cape Verde.

- Given my interest for especially the admixture scores it would have been useful if more detailed statistics had been provided, beyond the usual barcharts. Including also minimum and maximum scores for each island and for each type of admixture/source population. See also foot note 3. Already since Verdu et al. (2017) I have been especially eager to obtain greater insight into the exact admixture proportions of their Santiago study group. This has now been expanded from n=44 to n=59. But apparently still with only a minority of samples from the interior (Picos, see this screenshot).

3) Suggestions for future research

There have been quite a few DNA studies about Cape Verdean genetics already (see this overview). However plenty of interesting topics still exist which need further investigation. Also potential for breakthrough insights is still not fully realized. Profound novelties may yet be found! The DNA studies which have been reviewed in this blogpost appear to be focused mostly on follow-up research regarding how the various Cape Verdean islands were populated (the serial-founder hypothesis). In particular the admixture models explored in both Korunes et al. (2022) and Laurent et al. (2023).

More robust findings in that regard are certainly welcome! Of course also properly contextualized 😉 However I would argue that Caboverdeanidade is about so much more than just TAST related aspects! Below some suggestions which might improve our outlook on Cape Verdean genetics. Which again can also have added value for other Afro-descendants as well.

Sampling: apply criterium of 4 grandparents born on the same CV island

Table 3.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: Laurent et al. (2023). First study which provides samples for each populated Cape Verdean island! However many of these samples may have grandparents with different island origins. (Total and % column have been added by myself).

***

As already mentioned Laurent et al. (2023) is the only new DNA study which provides new sampling (n=225). The average African admixture for their entire Cape Verdean sample group was given as 59%. See footnote 3 for more details. The other two new studies are based on an older and still most numerous dataset (n=646) from Beleza et al. (2012/2013).

I was pleased to see the useful addition of samples from Brava, Maio and Sal. Because these islands have not been featured before in any DNA studies I am aware of. Although in my own research (n=100) I did have many Cape Verdean-American survey participants who could trace all of their family lines to Brava. This certainly allows a more representative outlook for Cape Verdean genetics as a whole. Even if still not fully corresponding with the current population distribution across the islands (compare last column of table 3.1 with this chart).

Then again, the Cape Verdean Diaspora is often said to be more numerous than the actual island population. And to truly do justice to the full spectrum of Cape Verdean diversity one should take them into consideration as well. Especially because due to historical reasons and so-called chain-migration many Cape Verdean descendants abroad might have stronger links with specific islands (such as Fogo and Brava in the USA, Santiago in Portugal and Barlavento in Northwest Europe). And therefore their combined average DNA profiles might also deviate somewhat from the national average in Cape Verde itself. See also:

In Laurent et al. (2023) it is mentioned that many of their samples had either parents or grandparents who were born on different islands. In some cases even from abroad (Angola, São Tomé etc.). This might be somewhat problematic. Given the intention to properly investigate inter-island differentation and clustering. For example most of their Santiago samples appear to be from the capital Praia. However it is known that this city has had a great influx of migrants from other islands (aside from the interior as well). Praia’s population grew from only 20,000 inhabitants in 1960 to a staggering 170,000 in 2020 (see this graph)! It is also known that people from São Vicente, the second largest island by population, often have recent ties to neighbouring Santo Antão. This also goes for me personally actually.16

This circumstance makes it all the more crucial that a “4-grandparents born on the same island” criterium is being applied. In particular when aiming to make statements about the historical population structure of each separate island. Of course populations are constantly changing and inter-island migration has been in existence for a longer time. Still the scale of modernday migration and hypermobility is clearly a new development which should be taken into account when striving for quality sampling.

Due to space constraints I haven’t been able to discuss the very intriguing research outcomes of Laurent et al. (2023) regarding how linguistics and genetics may correlate among Kriolu speakers in Cape Verde (see this chart). I hope to go more indepth with this at another time.17 In the interest of even more refined analysis for this research field I will suggest the following though. Perform dedicated sampling among older people living in the remotest part of the islands. I believe on Santiago the population from the interior is often referred to as Badiu di Fora. I know for Santo Antão people with the “thickest” accents are said to be talking “fund“. Usually stereotyped to be from the more remote ribeira’s (valleys). Given relative isolation I would assume that sampling these people will offer very precious testimony of both genetics and linguistics! A legacy which might now be under threat given the rapid modernization taking place in most islands.

More granular analysis of non-Senegambian/Iberian origins: Sierra Leone, Sephardi Jewish, Goa etc.

Table 3.2 (click to enlarge)

Source: 23andme. This is a screenhot of 23andme’s reference panel which they use for their admixture estimates. Actually quite similar to the Upper Guinean dataset being used in Laurent al. (2023). However notice the historically relevant Temne samples. This ethnic group from northern Sierra Leone has many documented links with Cape Verde. Historically referred to as “Sape” (see this page).

***

____________________

“The historical connections between Sierra Leone and Cape Verde have been quite significant during the 1500’s-1700’s, even when often unknown to the general public. Temne, a a language spoken by one of the biggest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone, has been identified as the source for several culturally meaningful words used in Cape Verdean Crioulo, such as “Tabanka” and “Funco” (see also Crioulo language). Its ancestral contribution to the Cape Verdean genepool might therefore have been underestimated.” (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

____________________

On 23andme the regional admixture category of “Ghanaian, Liberian and Sierra Leonean” used to be reported as a minor but still substantial African region for my Cape Verdean survey participants. Almost 10% of the African breakdown (see this chart). The “Senegambian & Guinean” region serving as a primary signature region for pinpointing Upper Guinean lineage (notice from table 3.2 that the very “matchy” Mandenka samples are being used for this category!). This was already a great indication of how Cape Verde’s Upper Guinean lineage is more diverse than often imagined. In fact on Ancestry the so-called “Mali” region probably serves a similar purpose. Often not realized by Cape Verdeans themselves because they tend to focus on Guiné Bissau. But for both historical and cultural/linguistic reasons especially Temne lineage might be rather common among Cape Verdeans.

However these ancestral ties to (northern) Sierra Leone and especially the Temne are most likely quite diluted. Because they must have joined the Cape Verdean genepool mostly during the 1500’s. For what it’s worth I have sofar not seen the genetic group of “Temne and Limba” being reported for any Cape Verdean sofar. Either way I remain very curious to see any further investigation into how much Sierra Leonean ancestry Cape Verdeans might have, on average.18

In fact within Laurent et al. (2023) they did use Mende samples from Sierra Leone (MSL in this chart). But no genetic affinity was found with their Cape Verdean dataset. I greatly suspect however that their analysis might be enhanced by adding Temne samples into their reference dataset. And furthermore also applying IBD matching strenght to measure any possible ancestral ties. Naturally using an appropriate threshhold level. The general consensus being that shared IBD segments should be atleast 7 or 8 cM, in order to avoid population matches (Identical By Population) or false matches (IBS= Identical by State). See also this link.

Table 3.3 (click to enlarge)

Source: my survey findings for 100 Cape Verdean 23andme results (2021). African and European admixture are of course primary for Cape Verdeans. Other types of admixture are usually minimal. However notice the maximum scores for Middle Eastern & North African (MENA) and South Asian admixture are well above trace level. In fact even the seemingly trivial, “noisy” Native American scores might yet turn out to be genuine for a subselection of Cape Verdeans. When combining with additional corroborating clues.

***

The 3 new DNA studies focus exclusively on African (SSA) and European admixture analysis. For their modelling purposes this is indeed justified and also convenient.19 However many Cape Verdeans do have other types of lineage as well. Usually to a minor degree. But still worthy of further investigation! I find that personal DNA testing results on Ancestry and especially 23andme are far more informative in this regard. Providing regional admixture categories from all over the world. Additionally also zooming into more specific and recent lineage by way of their genetic groups / DNA communities. Both these tools based on IBD (Identical by Descent) segment matching.

For example in my 23andme survey the maximum score for 14% “Middle Eastern & North African” was obtained for someone of partial Moroccan Jewish descent. Such lineage is often also correctly pinpointed by the additional country match/genetic group (see this screenshot). Sephardi Jewish lineage among Cape Verdeans can date back from both relatively recent (1800’s) as well as quite distant time periods (1500’s). Obviously it will be more detectable in the former case. However plausible regional admixture scores (not only “MENA” but also “Italian” and “Ashkenazi”) can sometimes also be indicative of the older type of Jewish ancestry. Which has actually been documented quite extensively for the crucial settling period of Cape Verde.

From my survey efforts sofar it appears that this type of lineage might be most pronounced among people from Fogo. See also Table 3.4 below. Laurent et al. (2023) do not have any North African or Jewish samples in their reference dataset (which is still quite adequate and extensive otherwise!). However intriguingly they still report “a significant (albeit very reduced) signal for a shared ancestry with Tuscan TSI” for their samples from both Fogo and Brava. See Table 1.2.

This is pretty much in alignment with my own findings given that Jewish DNA can be modelled as having a significant “Italian” component. Regrettably Sephardi Jewish DNA is difficult to capture in just one single category. Unlike Ashkenazi Jewish. Hence the overlap with several interrelated admixture categories. I have discussed this topic several times already. So see also these previous blogposts:

- Overview of Jewish, North African matches being reported for 50 Cape Verdeans.

- “North African” percentages via Portugal, the Fula or directly from North Africa? (scroll down to secton 4)

- “Africa North”, “Middle East”, “European Jewish” and other minor regional scores (scroll down to section 6)

- North African matches reported for 50 Cape Verdeans (scroll down to section 3)

Table 3.4 (click to enlarge)

Source: my survey findings for 100 Cape Verdean 23andme results (2021).The island origins of my survey participants are not based on a 4 grand parents criterium per se. But often this was indeed confirmed by their profile details on 23andme or else by PM. Obviously the samplesize for each subgroup is quite minimal. However I suspect the relatively pronounced MENA for Fogo and somewhat elevated South Asian for Santo Antão, might also be replicated with greater samplesize. Compare also with my previous survey findings on Ancestry.

***

I have actually also been investigating South Asian admixture among Cape Verdeans. As can be seen in tables 3.3 and 3.4 this type of lineage is quite minimal going by group averages. Usually within noise range (<1%) and therefore to be critically assessed. On the other hand such scores were also surprisingly consistent for especially my survey participants from Santo Antão or with partial origins from that island. At times (7/100) also exceeding more than 1%. The highest score of 7.8% beyond a doubt being genuine and also specified by a Goa recent ancestor location (see this screenshot)!

This maximum score of “South Asian” admixture belonging to a known cousin of mine! Such lineage already being known from family lore. Intriguingly implying that also the more diluted scores might actually be genuine. Possibly inter-related to some extent but probably more than one Goan ancestor being involved. As far as I know this is the first time a Goa-Cape Verde connection is showing up in a genetic study. I aim to blog about these findings in greater detail eventually.

I suppose even the very minor Amerindian scores I have detected in my surveys (both on Ancestry and 23andme) could still be valid, in selected cases! Naturally to be corroborated very carefully with additional clues. However I suspect that Amerindian trace amounts could sometimes be an indication of distant Brazilian lineage. Even more so when there is also a clearly above average proportion of African admixture from either Lower Guinea or Central Africa. Naturally other ancestral scenario’s also remain possible. See foot note 7 of this page for an extensive discussion.

New research agenda involving Cape Verdean Diaspora

Map 3.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: Jørgen Carling. Based on estimates. The USA and Portugal are often said to host the biggest communities of Cape Verde-descendants. But really Cape Verdeans can be found all over Europe. And also in quite a few African and South American countries. However several destinations in the Caribbean and Pacific are lacking from this map!

Source: Jørgen Carling. Based on estimates. The USA and Portugal are often said to host the biggest communities of Cape Verde-descendants. But really Cape Verdeans can be found all over Europe. And also in quite a few African and South American countries. However several destinations in the Caribbean and Pacific are lacking from this map!

***

The Cape Verdeans are a well-studied population among international researchers for several reasons. Not only because of Cape Verde’s pioneering Creolization. But also because of its widespread Diaspora which is the result of many migration waves. Principally during the 1800’s and 1900’s. So after TAST! Basically people were forced to leave their home islands due to a lack of economic opportunities but also because of recurring droughts. According to most estimates nowadays more Cape Verdean descendants are living abroad than on the islands themselves!

The USA is sometimes even said to host almost as many Cape Verdean descendants as Cape Verde itself. Although arguably this depends on how strictly you want to apply your criteria. Also keeping in mind the longstanding presence of Cape Verdeans in America: the first Africans to migrate to the USA out of their free will and even at times on self-owned ships! A truly awe-inspiring saga! The Cape Verdean migrant communities in Europe tend to be of a more recent date. The Cape Verdean presence in Upper Guinea is the oldest one and arguably goes back to the Luso-Africans from the 1500’s. Although later on reinforced with modernday migrations as well, especially to Senegal.

Being employed on whaling ships brought Cape Verdeans not only to the USA but also to many other parts of the world. And the amazing thing is that personal DNA testing is now clearly revealing Cape Verde-descendants also exist throughout the Pacific, Caribbean and even the Arctic! I have seen dozens of DNA results which unmistakingly indicate Cape Verdean lineage for people from Bermuda, Hawaii, New Zealand, Tonga etc. and even Alaska! Not only by way of tell-tale admixture scores for either “Senegal” or “Senegambian & Guinean”. But even more convincingly by way of countless DNA matches with confirmed Cape Verdeans. At times also resulting in a Cape Verde-related country match or DNA community.

Aside from whaling connections Cape Verdeans also migrated to especially Guyana as contract labourers during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Similar to the more numerous migrations from Madeira. Again quite surprising because many people will not be aware of these connections. I aim to blog about all of this eventually in greater detail. Because I find this super interesting! It is also yet another reminder that not everything about Cape Verdean DNA is TAST related 😉 For more background information in the meanwhile:

- Cape Verdean Diaspora or Afro-Diapora? (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

- Cape Verde will map its diaspora by 2026 to produce official statistics (Brava News, 2023)

- Transnational Archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean Migration and Diaspora (alternative link)

- Guyanese 23andme results showing Cape Verde as country match (scroll down for it)

___________________________________________________________________________

Notes

1) I discovered the indispensable Slave Voyages website around the same time I received my own 23andme results in 2010. Almost 15 years ago now already! And ever since I have often relied heavily on the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database as some sort of baseline. To establish historical plausibility within my ongoing research efforts on how personal DNA test results (regional admixture & African DNA matches) of Cape Verdeans and other Afro-Diasporans may already be in alignment with historical expectations. See these pages for an overview:

- 23andme surveys (2011-ongoing)

- Ancestry surveys (regional admixture: 2013-2018)

- Ancestry surveys (DNA matches: 2017-ongoing)

In 2015 I established that (as expected) Cape Verdeans are greatly uniform in their African origins, overwhelmingly hailing from Upper Guinea (but not for 100%!). In particular when contrasted/compared with other survey groups from across the Afro-Diaspora, which I blogged about for the first time in 2016. This outcome has been replicated in all my subsequent surveys. Which also indicate a so-called Upper Guinean Founding Effect for many Hispanic Americans. Similar to Cape Verdeans also mostly to be traced back to the 1500’s.

Actually my very first survey efforts date back even earlier to 2011. Based on the pioneering African Ancestry Project by Razib Khan. I shared these findings also on 23andme’s online community at that time. They can still be seen in this online spreadsheet. Already then I was able to make good use of Cape Verdean DNA results as some sort of control group within a broader dataset of Afro-descendants. Albeit that of course the sample size was very minimal, given that personal DNA testing had not yet become popular.

This early research opened my eyes to the fact that Cape Verdeans form a special part of the Afro-Diaspora, given that their African roots are overwhelmingly from Upper Guinea. And this should also be reflected in their DNA results (if they are any good ). In this case a tellingly pronounced genetic affiliation with “Mandenka” showed up already in 2011 (see this overview)!

Unlike commonly assumed you do not need to sample entire populations to obtain informational value with wider implications. Naturally greater sample size does (usually) help matters. However I find it reassuring that in many aspects peer reviewed studies based on larger sample size have vindicated my own earlier findings. While due to free format on my blog I am often able to provide greater detail and more appropriate context.

In my latest survey efforts (based on both 23andme and Ancestry results) my Cape Verdean survey group has taken a more robust sample size of n=100. And I aim to expand especially the coverage of DNA results from Santiago, Maio, Boavista and Sal. Continued corroboration of my own research is not only to be seen in the DNA studies reviewed in this blogpost. But also a few years ago my survey findings were replicated by the huge study performed by 23andme’s research team:

- Genetic Consequences of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Americas (Micheletti et al., 2020) (go to section 2 for Cape Verde related discussion)

2) The earliest summary of my Cape Verdean survey findings was put online in 2015. Which was (as far as I know) the first ever demonstration that Cape Verdeans are overwhelmingly Upper Guinean in origins. When looking only at their African DNA and based on autosomal genotyping. Previous haplogroup studies (see this link) did also come to the same conclusion. However they were restricted in the sense that they didn’t measure the complete, genomewide ancestry of Cape Verdeans but only focused on maternal lineages.

To specify the overlap with my own research more clearly. See below for an overview of aspects about Cape Verdean genetics which I already established several years ago.

1) Cape Verdeans being mainly an Upper Guinean/Iberian mix: 2018, 2021

2) Interisland differentiation/substructure: 2015, 2018, 2021

3) Minor non-Upper Guinean lineage: 2015, 2018a, 2018b, 2021

4) Comparison with other parts of Afro-Diaspora: 2016, 2018a, 2018b, 2021

5) Recent ancestry (1800’s) from Portugal & Upper Guinea: 2018a, 2018b, 2022

Furthermore my own research has also gone beyond what has been published sofar by peer reviewed studies. In particular for these aspects:

1) IBD matching patterns (Ancestry, 23andme): 2018, 2022

2) Analysis of North African/Sephardi Jewish lineage: 2015, 2018a, 2018b

3) Analysis of South Asian and Amerindian lineage: 2018a, 2018b, 2021

4) Indications of Northwest European lineage: 2013, 2018, 2021

3) Regrettably the new DNA studies do not really provide detailed African admixture statistics per island. Instead the usual bar charts are featured. For Hamid et al. (2021) and Korunes et al. (2022) this doesn’t matter. Because both studies are relying on older datasets from Beleza et al. (2012/2013). See chart 4 in this blogpost for more details. However in Laurent et al. (2023, pp.5-8) the following statement is given regarding African admixture per island:

____________________

“Membership proportions for this [African] cluster are highly variable across Cabo Verdean islands, with highest average memberships for Santiago-born individuals (71.45%, SD = 10.39%) and Maio (70.39%, SD = 5.26%), and lowest for Fogo (48.10%, SD = 6.89%) and Brava (50.61%, SD = 5.80%).”

____________________

The average African admixture for their entire Cape Verdean sample group (n=225) was given as 59%.

4) Within Laurent et al. (2023) two methods are being used to arrive at their “ethnicity estimates”. The first one involves the classical ADMIXTURE software. I have actually had my own DNA analyzed in this manner all the way back in 2011 already 🙂 This method requires very careful interpretation because the outcomes are greatly dependent on the selection of the reference populations. As well as the number of so-called K-runs. Potentially misleading when taken too literally! Quite comparable to the various admixturetools on GEDmatch which are known to be greatly variable and confusing! As stated by the authors themselves:

____________________

“The resulting ADMIXTURE patterns could be due either to admixture from populations represented in our dataset, to admixture from populations un-represented in our dataset, or to common origins and drift.” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.9).

____________________

Furthermore they also apply SOURCEFIND for their so-called local ancestry inference, as shown in figure 1.2. It is important to grasp that this type of analysis is based on quite a low level of granularity. When compared with what is provided by personal DNA testing companies such as 23andme and Ancestry. Given the limitations of only 4 or 6 source populations. But also apparently going by 100 possible admixture “slots” only. The way the results are presented appears to me to be quite similar to the Oracle predictions, also on GEDmatch. Certainly useful at times, but again very dependent on careful interpretation.

____________________

“We […] conducted two SOURCEFIND (Chacón-Duque et al., 2018) analyses using all other

populations in the dataset as a possible source, separately for four or six possible source populations (‘surrogates’), to allow a priori for symmetric or asymmetric numbers of African and European source populations for each target admixed population. […]Each individual genome was divided in 100 slots with possibly different ancestry, with an

expected number of surrogates equal to 0.5 times the number of surrogates, for each SOURCEFIND analysis.” (Laurent et al., 2023, p.31).

____________________

5) Laurent et al. (2023) seem to not have been fully aware of how Cape Verde’s slave trade was overwhelmingly carried out with Upper Guinea during the 1500’s. Even when this is extensively discussed in the sources they list themselves in their references (see foot note 8). This leads them to inaccurate and highly speculative interpretations of their minor Lower Guinean & Central African findings (see last paragraph p.69).

____________________

“Numerous enslaved-African populations from […] Central Africa were forcibly deported during the TAST to both Cabo Verde and the Americas, as shown by historical demographic records (1,25). There is still extensive debate about whether enslaved-Africans remained or more briefly transited in Cabo Verde during the most intense period of the TAST, in the 18th and 19th centuries, when the archipelago served as a slave-trade platform between continents.” (Laurent et al., p.23).

“However, historical records unquestionably demonstrated that numerous other populations from West Central and South Western Africa were enslaved and forcibly deported to Cabo Verde during this era [1700’s].” (Laurent et al., p.69).

____________________

The statements above are wrong for several reasons:

- TAST numbers for Cape Verde peaked during the 1500’s and not the 1700’s/1800’s (see figure 2.1).

- During the 1400’s/1500’s it was explicitly forbidden for Cape Verde to have any slave trading activities beyond Sierra Leone (see these sources). Curiously Laurent et al. (2023) do mention this with extensive references even on page 27, but they do not process this information elsewhere.

- During the late 1600’s and 1700’s a low-volume and sporadic slave trade was carried out clandestinely by Northern Europeans. Aside from also various Portuguese state monopolies. Most notoriously the Grão Pará and Maranhão Company. Purely to cover a (weak) domestic demand of enslaved labour and not for transit purposes (see these sources).

- Only during the 1800’s there was a short-lived revival of Cape Verde acting as a transit hub for TAST again. But at that time enslaved people were less than 5% of the total population in Cape Verde. (see Table 2.2)

- Most of these late arrivals from the 1700’s/1800’s would still be almost exclusively from Upper Guinea. During a very detailed slave census held in 1856 enslaved people from Lower Guinea (Costa da Mina) or Central Africa (Angola and Cabinda) were very rare and clearly exceptional. Also adding persons from Brazil and Cuba they merely represented 6 individuals out of a total of 5182 persons, a miniscule 0,1%! (see census 1856).

- Also due to nautical reasons (trading winds, currents) it was not convenient to make a stop in Cape Verde for outgoing TAST voyages departing from Central Africa or even Lower Guinea (Windward Coast up to Bight of Biafra). At times this might still have happened but it seems only very sporadically so. After all these adverse nautical circumstances (such as the Guinea current) would have been widely known in this Age of Sail.

Naturally this forcible linking with generic TAST patterns is not beneficial for understanding the minor Lower Guinean and Central African admixture among Cape Verdeans! I was surprised that an arguably much more plausible scenario (among others) was not mentioned in Laurent al. (2023). That is to say African geneflow from Lower Guinea and Central Africa might have ended up in Cape Verde by way of detour via other parts of the Portuguese colonial empire.

Not only restricted to intermingling with enslaved persons but also in fact free and/or mixed-race persons from either Brazil, Angola, Mozambique or São Tomé & Principe. Back & forth migrations as well as more fleeting stop-overs by sailors are all realistic scenario’s I suppose. A strong increase of either Lower Guinean or Central African admixture could very well be indicative of a more recent intermingling. Aside from solid family tree research also to be corroborated by IBD matching patterns.

6) Based on all DNA studies published sofar it can already be safely concluded that Cape Verdeans can be distinguished in several subclusters based on island origins. The basic divide being between the northern Barlavento and southern Sotavento (see this map). This theme of substructure between the islands is something I myself have actually also been investigating since atleast 2015.