Contents

- Introduction

- Summary of Findings

- Observations

- “Ivory Coast/Ghana” also predictive of Liberian DNA

- “Benin/Togo” also predictive of Ghanaian & Nigerian DNA

- AncestryDNA regions correlating with language?

- Ancient migrations & spread of agriculture

- Screenshots & Youtube videos of West African AncestryDNA results (2013-2018)

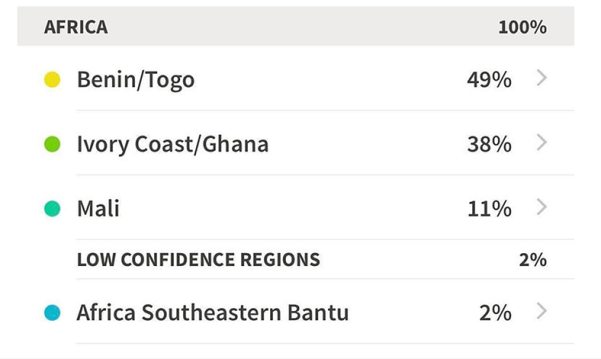

- Implications for Afro-Diasporans

- How to make more sense of “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores

- How to make more sense of “Benin/Togo” scores

________________________________________________________________________________________

UPDATE 03-09-2019: this page was first published on 21 February 2018 when I had only 41 AncestryDNA results available from this part of West Africa for my analysis (see this overview). As my survey has been ongoing I have managed to collect a sample group which has now doubled in size. Consisting of no less than 82 AncestryDNA results from Liberia, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Ghana & Benin! Additional screenshots and new group averages have been added therefore. Also a few textual changes have been made (see this link for original version).

For a short recap of my final survey findings follow this link:

Please also keep in mind that AncestryDNA’s ethnicity estimates have been updated several times now! On this page I am dealing exclusively with AncestryDNA version 2 which was current between September 2013 and September 2018. All matters being discussed on this page are therefore not pertaining to updated results (Sept. 2018 up till now). In my opinion this version 3 regrettably has been a downgrade rather than providing meaningful improvement, overall speaking. Which is why I have discontinued my AncestryDNA survey. For more details read this blogseries:

- Did Ancestry kill their African breakdown? (part 1)

- Did Ancestry kill their African breakdown? (part 2)

- Did Ancestry kill their African breakdown? (part 3)

________________________________________________________________________________________

1) Introduction

On this page I will be posting AncestryDNA results of West Africans with confirmed ethnic background(s). Unlike for Afro-Diasporans in the Americas these results can therefore be verified with known genealogy. This should be helpful to improve correct interpretation and also to determine how reliable/predictive the various African AncestryDNA regions might be.

This discussion of West African AncestryDNA results will be divided in two parts, each having its own page. Roughly corresponding with the categorization of Lower Guinea & Upper Guinea. And also in approximate alignment with a preponderance of either “Ivory Coast/Ghana” or “Benin/Togo” scores (see map 2) instead of “Senegal” and/or “Mali” scores among my West African survey participants. See also:

- Research methodology for my AncestryDNA survey

- Spreadsheet featuring individual West African AncestryDNA results

- Spreadsheet featuring group averages for West African AncestryDNA results

Liberia, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo & Benin

Map 1.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: https://mapchart.net/africa.html

***

Map 1.2 (click to enlarge)

***

Specifically on this page I will focus on results from Liberia, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo and Benin (shown in red in map 1.1). Nigerian results have already been discussed on a separate page (any future results from Niger & Chad will be posted there as well). Results from the remaining West African countries (shown in green in map 1.1): Senegal, Gambia, Mali, Mauritania, Guinea Bissau, Guinea Conakry and Sierra Leone will be discussed in the second part of this exploration of West African DNA results. I will first present a summary of my main findings in section 2. I will provide more detailed analysis & relevant context in section 3. In the very last part of this page (section 5) I will discuss the implications these West African results might have for Afro-Diasporans. If you want to skip the discussion just scroll to section 4 to see screenshots of individual West African AncestryDNA results.

The screenshots of these various West African AncestryDNA results form the basis of my survey findings. I have grouped them by country and when possible also by ethnicity1. The backgrounds behind these West African results were verified by me in the best way I was able to. Mostly based on statements made by the persons who did the AncestryDNA test but in a few cases I also distilled a likely ethnic/national identity by way of other clues (usually family names and family locations). In these latter cases I have added a question mark in the header. Therefore a 100% accurate depiction of self-identification is not intended. The ethnic headers are merely meant to provide additional perspective. Even if at times only approximate info was available to me. Naturally I respect everyone’s right to self-identify as they please. My accompanying comments should be taken as informed speculation on my part they are not meant to exclude other possibilities or simplify complex family histories.

As these results below show many West Africans are in fact of “mixed” background if you go along with the regional framework provided by AncestryDNA. As I will continue to say it is counter-productive to get distracted by the country name labeling. Rather consider the AncestryDNA regions to be proxies of ancestral components which have become more frequent in certain loosely defined areas but still show a wide dispersal in neighbouring areas as well due to ancient migrations and inter-ethnic unions occurring probably since the dawn of mankind! If you invest some time in learning how to truly “read” the results they can still be very informational in my opinion.

I like to thank all my West African survey participants for having tested on AncestryDNA and sharing their results so that it may benefit other people as well!2 See also:

- African AncestryDNA results

- Central & Southern African results

- North & East African AncestryDNA Results

- Nigerian AncestryDNA results

- West African results part 2

_____________________________________________________________________________

2) Summary of Findings

Selection of West African AncestryDNA results

***(click to enlarge)

***(click to enlarge)

***(click to enlarge)

***

In my personal estimation AncestryDNA can report valuable information about your ancestral origins as long as you interpret the data correctly and as long as you are also aware of the relevant context and inherent limitations. Still these results might appear to be “off” at first look for those not accustomed to how AncestryDNA or DNA testing in general works. Therefore please keep in mind the following disclaimers:

- Don’t take the country name labeling of the regions too literally. The regional percentages firstmost signal close genetic similarity to the samples taken from the countries after which the regions have been named. Actual origins from neighbouring countries should not be ruled out.

- Almost all African countries have been colonial creations with borders cutting right through the homelands of ethnic groups. Closely related ethnic groups can often be found on both sides of the border.

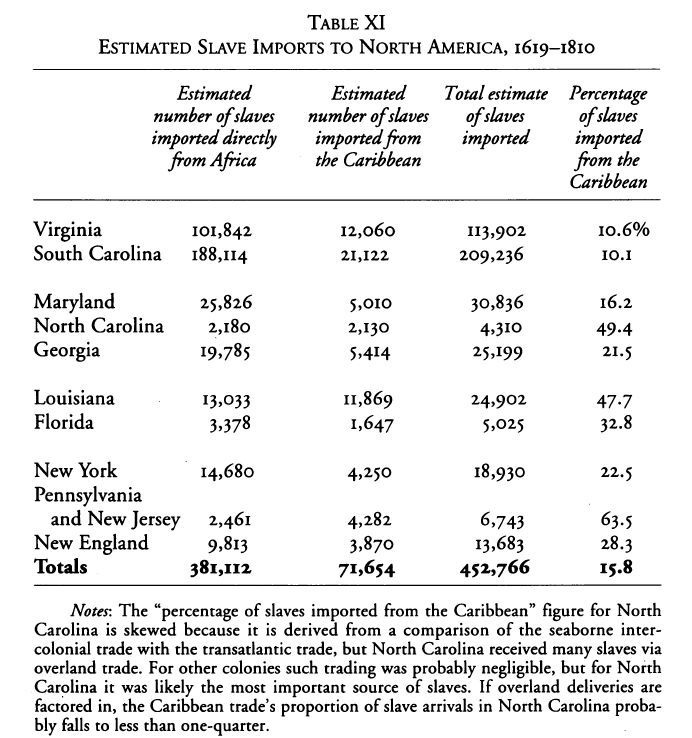

- Most DNA is common in many populations, just at different frequencies. Due to either migrations or shared origins dating back from hundreds or even thousands of years. For this part of West Africa in particular the migrations associated with speakers of various language groups such as Kwa, Gbe, Gur and Kru are a factor of paramount significance.

- Sometimes (very) ancient admixture rather than any recent lineage is suggested by these AncestryDNA estimates. And in this way some of these regional scores might perhaps best be seen as genetic echoes from a (very) distant past. Beyond family tales, historical knowledge or even ethnic origin traditions.

- Ethnicity is a construct which evolves across time due to ethnogenesis. Generally speaking therefore ethnic groups do not possess unique DNA markers. Especially in comparison with neighbouring ethnic groups or from within the same wider region. The most common scenario being a genetic gradient which causes ancestral components to gradually fan out. As can be verified from my survey.

- However by closely studying the regional combinations being reported for West Africans we can still learn a great deal. Inspite of individual variation group averages do tend to provide more solid ground to make meaningful inferences when specifying someone’s ancestral origins. Also finding out where a specific region is most prominent or rather most subdued holds valuable lessons.

West African group averages

***

The statistical data displayed in chart 2.1 is based on a limited sample size. Although almost all countries are being covered now (incl. also Burkina Faso!). While the sample size for Liberia and especially Ghana is quite decent actually. Which should contribute to a more robust dataset when compared with my initial findings in 2018 (n=41, see this overview). All of the included countries themselves do harbour a multitude of ethnic groups. Right now however I can only make statistic calculations for a few well represented ethnic groups within Ancestry’s customer database. It should be obvious therefore that a greater degree of genetic diversity and individual variation might be expected across West Africa and also within the listed countries.

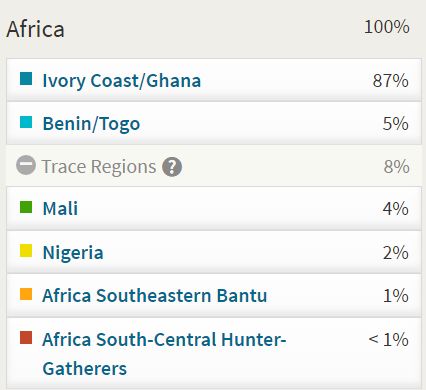

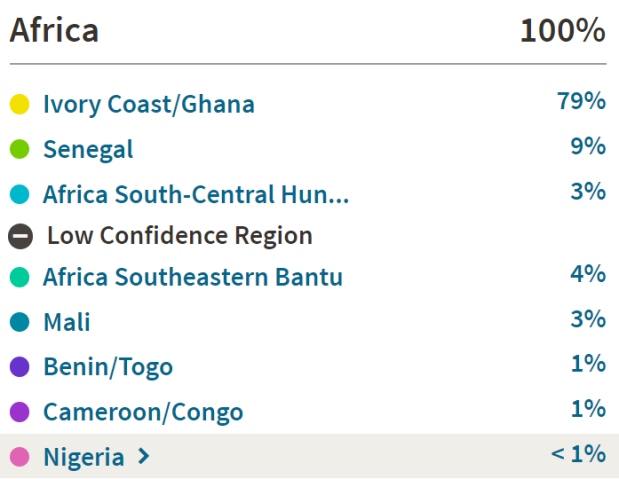

Some of this diversity is already being shown by the Ghanaian results representing half of my sample group (for this part of West Africa). We can verify that the so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region is indeed quite predictive for the 18 Akan samples (88%) and to a lesser degree also for the 4 Ga-Adangbe samples (69%). However for the 6 Ewe samples it is instead so-called “Benin/Togo” which is most prominent (67%)! This is something I had anticipated right from the start when I began my AncestryDNA survey five years ago already in 2013.

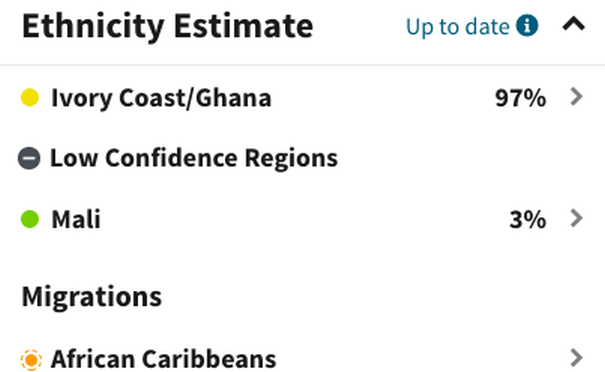

Eventhough only preliminary statements should be allowed at this stage I highly suspect that these group averages are already a reasonably good approximation of the main regional components to be found within the genepool of this part of West Africa. Atleast according to AncestryDNA’s current reference panel. The group averages I have calculated being more less in line with how the “typical native” scores according to Ancestry’s information: respectively 86% for “Ivory Coast/Ghana) (n=115) and 82% for “Benin/Togo” (n=60).

However also other regions are frequently reported. Either as minor genetic components with lower confidence but often also with substantial amounts above trace level. Nearly always neighbouring and genetically overlapping West African regions are involved. This goes especially for so-called “Nigeria” in regards to results from Benin; so-called “Benin/Togo” in regards to results from Ghana; so-called “Mali” in regards to results from Ivory Coast and so-called “Senegal” in regards to results from Liberia. In a way these main secondary regions help make each nationality more recognizable rather than just focusing on their primary regions which are in no way unique to any given country! It is also noteworthy how so-called “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” (labeled “Pygmy/San” in my survey) is consistently showing up for results from Liberia and also to a lesser degree for results from Ivory Coast. For more discussion:

These extra regions may be unexpected at first sight for people who according to their own knowledge are “100%” Liberian, Ivorian, Ghanaian, Beninese etc.. Taking these results at face value can therefore be misleading without correct interpretation. The disclaimers I already mentioned above as well as the next section below should provide sufficient clarification. As actually this outcome does overall still make sense. In short the advise would be to: don’t overfixate on the labeling of ancestral categories! In fact this does not only go for AncestryDNA but any kind of admixture analysis. In order to avoid jumping to premature conclusions I highly recommend that you atleast browse through some of the topics mentioned in the following links:

- AncestryDNA Ethnicity Estimate Help and Tips (Ancestry)

- AncestryDNA regions (Tracing African Roots)

_____________________________________________________________________________

3) Observations

“Ivory Coast/Ghana” also predictive of Liberian DNA

Map 3.1 (click to enlarge)

***

One of the main outcomes of my West African survey is that based on group averages so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is most prevalent in Liberia. And not as you might assume in either Ivory Coast or Ghana. Although the group averages are actually not that far apart (see chart 2.1). Liberia is currently not featured with its own region on AncestryDNA. That’s why it is only logical that Liberian DNA will be described in terms of the existing 9 African regions. Given Liberia’s geographical location an intermediate outcome between “Ivory Coast/Ghana”, “Mali” and “Senegal” was to be expected therefore. To be sure all of these three regions do indeed show up in Liberian results. But by far “Ivory Coast/Ghana” has turned out to be predominant. Even when for one result it was instead “Senegal” which was the biggest region. Undoubtedly this is linked to ethno-linguistical background as will be explained further below.

Actually so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is also being reported with substantial amounts in Sierra Leone. Much for the same reasons as for Liberia, its neighbouring country. Afterall Sierra Leone is also not appearing with its own region on AncestryDNA. The Sierra Leone context is however more complex because it seems to have a greater Upper Guinean influence (“Senegal” and “Mali”) compared with Liberia. Furthermore also the usually quite mixed (within Africa) background of the Krio people complicates any straightforward interpretation. This will be discussed in greater detail in “West African Results, part 2”.

Based on what I have seen I can already say that it might be expected that especially Mende people and other ethnic groups from southern Sierra Leone will score high “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores. On average perhaps in the range of 40-50%. The “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region is also frequently showing up (above trace level) in the results of other West African countries. As far north as Senegal and as far east as Nigeria (also mentioned in map 3.1). However much more subdued and never as primary region, unlike what I have observed several times already for Sierra Leone (see my spreadsheet).

Then again “Ivory Coast/Ghana” can of course also be very predictive of either Ghanaian or Ivorian DNA. But as my survey is demonstrating only as as long as you fit a certain ethnic profile. Keeping in mind that my sample size is still limited the highest “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores (>90%) have been obtained for persons with either an Akan or Kru background. To be sure this does not mean that “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is an indicator of actual Akan or Kru descent! Other ethnic backgrounds might still be perfectly compatible with high “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores. However this finding does seem to suggest that AncestryDNA might use samples taken from both Akan & Kru populations to calculate their so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” estimates.

As far as I know Ancestry has not confirmed the ethnic backgrounds of their African Reference Panel. However just speculating I would say it’s very likely that Brong (Akan speaking) samples from Ghana were used. Possibly combined with Ahizi (Kru speaking) samples as well as Yacouba (south Mandé speaking) samples. Both from western Ivory Coast. The Brong appeared in a pre-release version of AncestryDNA (see this screenshot). While the Ivorian samples have been used for atleast two genetic studies already (Brucato et al., 2010 & Fortes-Lima et al. 2017) and might have been included in the now defunct Sorenson Database which was bought by Ancestry.com a few years ago. Although again I have no certainty about this.

Such a selection of samples might explain why Liberian Kru results and Ghanaian Akan results show the highest “Ivory Coast/Ghana” amounts I have observed during my survey. It would simply mean that genetically speaking they are a near perfect match to the samples within AncestryDNA’s database. Naturally so if these samples happen to be Akan and Kru like themselves! The possible inclusion of Mandé speaking Ivorian samples (Yacouba) might then explain why “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores are still so frequently reported also across Upper Guinea as well as south Mandé speakers in Liberia. I need more results from those countries to confirm though. I only managed to include one result from Burkina Faso. And it might be expected that, given wider variation, “Ivory Coast/Ghana” will be reported in substantial amounts over there as well.

“Benin/Togo” also predictive of Ghanaian & Nigerian DNA

Map 3.2 (click to enlarge)

***

Map 3.3 (click to enlarge)

***

In my West African survey I have included nine results from Benin (almost all with a Gbe speaking background). And their “Benin/Togo” scores (70% on average and with a 79% median, see chart 4.2) are in line with what Ancestry mentions about the score of the “typical native” being 82%! Of course this represents only a limited sample size but it does testify to the predictive accuracy of this region. I have however also come across substantial and even impressingly high so-called “Benin/Togo” scores for people from other countries than either Benin or Togo. Most notably (eastern) Ghana and (southern) Nigeria. But surprisingly also among people of the Afro-Diaspora coming from places with relatively few documented direct ancestral connections with either Benin or Togo. I have already blogged about these findings because they were seemingly so counter-intuitive at first sight:

- Is “Benin/Togo” really pinpointing origins from within Benin’s borders?

- Nigerian AncestryDNA results (scroll to section 4)

My ongoing survey now allows me to more solidly confirm what I had previously already outlined in the blog pages referenced above. The “Benin/Togo” region can indeed be predictive of genuine Beninese ancestry but not exclusively so! Keeping in mind that my sample size is still limited, the highest “Benin/Togo” scores (>80%) have been obtained for persons with a Gbe speaking background. For one Ewe person from Ghana it was even as high as 97%! To be sure this does not mean that “Benin/Togo” is an indicator of actual Gbe or Ewe descent! Other ethnic backgrounds might still be perfectly compatible with high “Benin/Togo” scores. However this finding does seem to suggest that AncestryDNA is using samples taken from Gbe-speaking populations to calculate their so-called “Benin/Togo” estimates.

Knowing the history (ca. 1000-1500 AD) of the Gbe migrations (see map 3.3), originating in southern Nigeria and spreading westwards across Benin & Togo into eastern Ghana, is crucial to gain deeper understanding. And also just being aware that West African ethnic groups are often spread across borders and share a great degree of ancient origins with neighbouring groups is essential. Either way I imagine this finding could really be an eye-opener for many people looking to interpret their so-called “Benin/Togo” results. It puts the reporting of so-called “Benin/Togo” scores into much better perspective. Both for Ghanaians and (southern) Nigerians, but also for Afro-Diasporans (see section 5 for implications).

I like to underline that so-called “Benin/Togo” is not an exclusive marker for any given ethnic group or nationality. Both according to Ancestry’s own info (see map 3.2) as well as my survey findings it could be suggestive of many different ethnic origins from eastern Ghana into southern Nigeria, while possibly also some ethnic groups further west such as the Gur speaking people in Burkina Faso and northern Ivory Coast might score substantial amounts for this region as well. This geographical range ultimately to be explained mostly by shared ancient origins from Nigeria rather than from Benin or Togo.

AncestryDNA regions correlating with language?

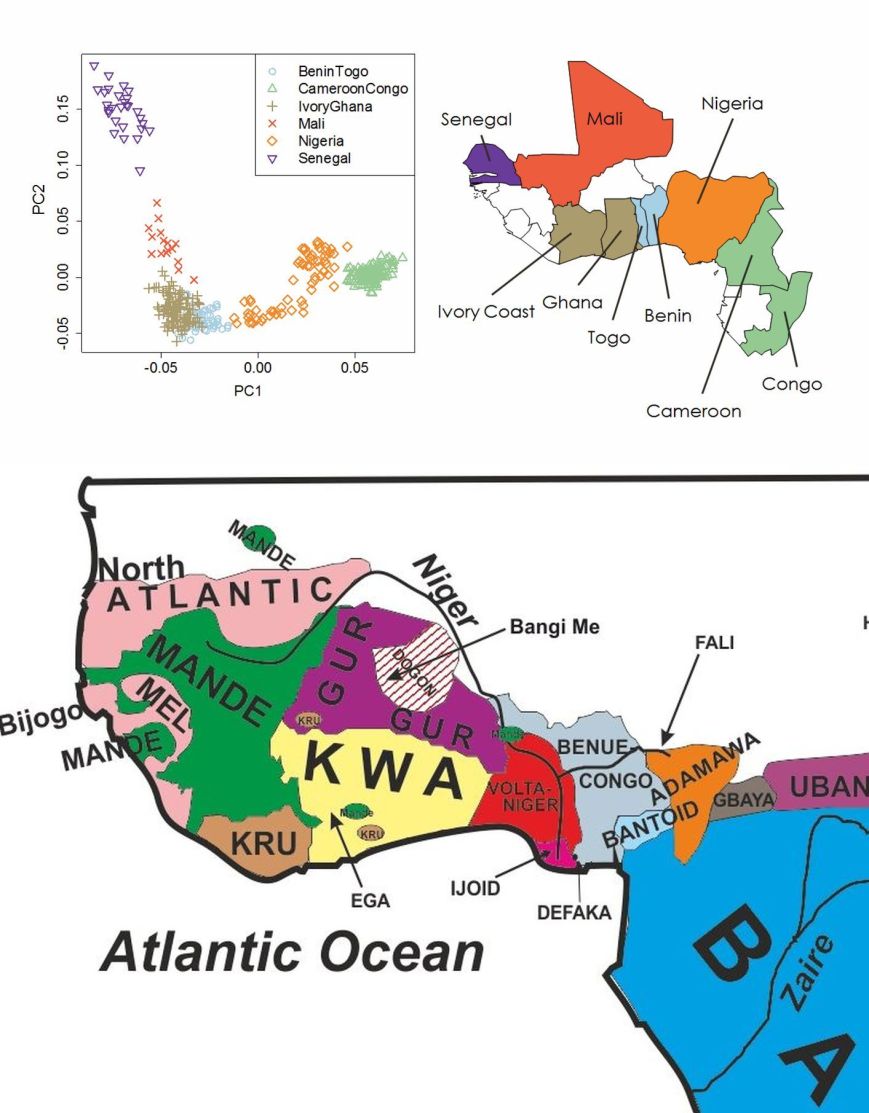

Map 3.4 (click to enlarge)

Source: Ancestry (2013) & Roger Blench (2012)

***

From my experience learning about ancient migrations and the distribution of African language groups can be very helpful to make more sense of your AncestryDNA results. I like to point out from the start that what’s about to follow is still mainly my own personal take on it and not intended to be conclusive in any way. Map 3.4 features a PCA (principal component analysis) plot of the West African regions on AncestryDNA as well as a map of West Africa’s main language groups. Taking a cue from this juxtaposition it seems to me that roughly speaking:

- The so-called “Senegal” and “Mali” regions correspond mainly with the distribution of Atlantic and Mandé languages. All concentrated within the area which is also known as Upper Guinea.

- The so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region seems to coincide mostly with the area where both Kwa and Kru languages are spoken.

- So-called “Benin/Togo” seems to be associated first of all with the Volta-Niger languages (which includes both Gbe languages and Yoruba as well as Igbo).

- So-called “Nigeria” would in fact also be including Volta-Niger languages. Creating major overlap, even when shifted more eastwards. But in addition it’s probably also covering all other major language groups native to presentday Nigeria (incl. also Chadic speaking Hausa’s, not shown in the map but based on my Nigerian survey findings).

- These last three AncestryDNA regions (“Ivory Coast/Ghana”, “Benin/Togo” and “Nigeria”) together more or less envelop the so-called Lower Guinea area.

- Presently AncestryDNA does not have any separate region for Burkina Faso (which is mostly Gur speaking, see this map). The Gur languages are therefore probably being covered by a mixture of “Ivory Coast/Ghana” with “Mali” and in selected cases also some “Nigeria” or “Benin/Togo”.

- So-called “Cameroon/Congo” is a bit out of scope because it is principally linked to the Bantu languages (shown in blue) from Central & Southern Africa. But it also connects with the closely related Bantoid languages within the border area of Cameroon & Nigeria which gave rise to the Bantu expansion.

To truly digest this information you will first need to resist the (unrealistic) urge to see everything in “exact” and “precisely” delineated terms. Instead attempt to focus on approximate tendencies and rough correlations to be observed within a bigger context. This can help you gain greater insight from your results. In particular for Africans taking the AncestryDNA test there is no need to panic when your results show less than 50% for whichever region you happen to be “native” of or whichever region you expected to be most relevant given your background. As long as your main breakdown consists of a plausible combination of neighbouring regions there should be no cause for immediate concern 😉

DNA testing is revealing that usually ethnicity cannot be distilled into one single genetic category, unless you happen to be a perfect match to the samples your DNA is being compared to. Instead typically most ethnic groups will be described as a composite of neighbouring and interrelated ancestral categories. This might be counterintuitive at first but does actually make sense if you take into consideration the genetic impact of shared origins, ancient migrations and inter-ethnic mixing throughout the ages. The distribution of language groups is a good indicator of the broader patterns to be taken into consideration. As generally speaking the initial expansion of distinctive populations was accompanied by the spread of their language and often also their particular mode of livelihood. Various scientific papers have already demonstrated that broad-scale population structure within Africa reflects both geography, (pre-)history and language. For example see:

- The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans (Tishkoff et al., 2009)

- Genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture in West Africans and African Americans (Bryc et al., 2010)

- Admixture into and within sub-Saharan Africa (Busby et al., 2016)

Although again not perfectly so! There will always be factors adding to complexity and things being less clearcut or consistent as you might wish for. Some reservations to keep in mind: language shift; cultural assimilation; deep ancestry predating ethnogenesis; whole scale absorption of ethnic minorities; ethnic blending because of trading diaspora’s, polygamy, local slave trade, increasing urbanization in multi-ethnic cities etc., etc.. For all these reasons people speaking the same or related languages might still have divergent DNA profiles because we all have unique genealogies which transcend ethnicity if you go back in (pre-)history far enough. Another aspect to be aware of is that the linguistic categorization of Africa’s languages is very much a project in progress! Even when the main outlines are pretty much agreed upon among most scholars already. See also:

- African Maps (Ethno-Linguistic, Lower Guinea, Upper Guinea, Sahel/Interior) (Tracing African Roots)

- African language materials (Roger Blench)

- Niger-Congo materials (Roger Blench)

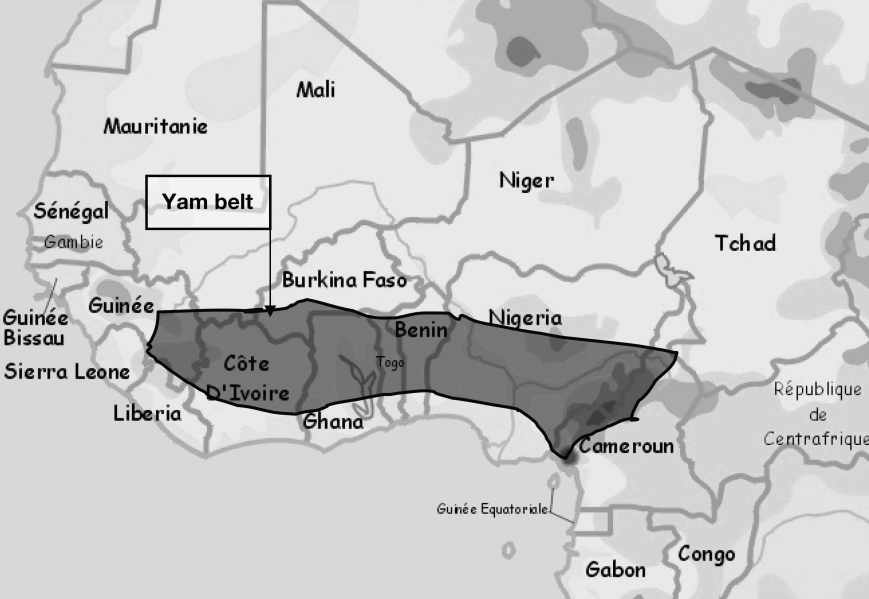

Map 3.5 (click to enlarge)

Source. Notice how the old grouping of Kwa languages used to extend from southern Nigeria into southeastern Ivory Coast. Also notice the presence of Kru languages in both Liberia & Ivory Coast.

***

Map 3.6 (click to enlarge)

Source. Notice how all 3 language groups are practically adjacent and crossing modernday country borders.

***

From Ancestry’s information (see this plot) it can be gleaned that the “Benin/Togo” and “Ivory Coast/Ghana” regions cluster the closest from all other African regions on AncestryDNA. And furthermore the samples from Benin/Togo and Ivory Coast/Ghana are the only ones that seem to overlap to some degree. From my Nigerian survey findings it has come to light that the “Benin/Togo” region is very commonly reported for southern Nigerians as well. Although usually as a secondary region. Less frequently and with lesser amounts “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is still also present among several Nigerian results. Suggesting that people in this broader area (Lower Guinea) are genetically speaking quite closely interrelated. Nonetheless it has turned out that if you resist from taking the country name labeling too literally these regions do seem to describe rather distinctive and separate genetic clusters, albeit loosely defined. “Ivory Coast/Ghana” to be associated mostly with Akan & Kru affiliations but possibly also indicative of south Mandé connections. While “Benin/Togo” is more so centred on Gbe affiliations, as well as southern Nigeria where the Gbe originated and still share a great deal of DNA. Together this would encompass the Volta-Niger language group.

Looking into maps 3.5 & 3.6 above it’s instructive to grasp how the Gbe languages of Ewe (Ghana/Togo) and Fon (Benin) are grouped together with southern Nigerian languages into one Kwa cluster. Nowadays also termed “Volta-Niger“, but formerly also known as eastern Kwa! It is even more illuminating to be aware that also the Kru languages from Ivory Coast and Liberia once used to be classified as Kwa (see this map)! Nowadays a finer distinction is being made and an independent or intermediate position with the Gur languages is often assumed (see this article for an overview). Still this doesn’t take away from the overall close relationships and a hypothetical ultimate origin from Nigeria. Aside from the well known and relatively recent Gbe migrations, this might otherwise be traceable to thousands of years ago rather than hundreds of years ago. Principally driven by the initial spread of agriculture throughout West Africa. And not to be confused with the more recent & convoluted split-migrations taking place in historical time periods. In particular the expansion of the Akan people as well as the southward drift of Mandé people in the past millennium. Apparently causing the Kru populations to migrate further into Liberia, coming in from presentday Ivory Coast.

Ancient migrations & spread of agriculture

Map 3.7 (click to enlarge)

Source: The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation (Newman, 1995)

***

Map 3.8 (click to enlarge)

***

____________________

“Also from Nigeria, some of the Kwa peoples spread in similar fashion through the West African tropical rain forest to the Ivory Coast and forced other Kwa peoples, the Kru and Lagoon speakers, westward into the Ivory Coast and Liberia. […]

“Agriculture has since been introduced to most of the Kru and Lagoon peoples, but it usually has rice as the basic crop, which comes from a different center of dispersal, or manioc, which was introduced into West Africa from the New World. Even today in the Ivory Coast, as several botanists (Miege 1953; Chevalier 1952) have remarked, there is a sharp boundary of yam cultivation on the Bandama River, which is also the border between the Baoule [Akan] and Kru peoples.” (Anthropological Implications of Sickle Cell Gene, Livingston, 1958, p.552)

____________________

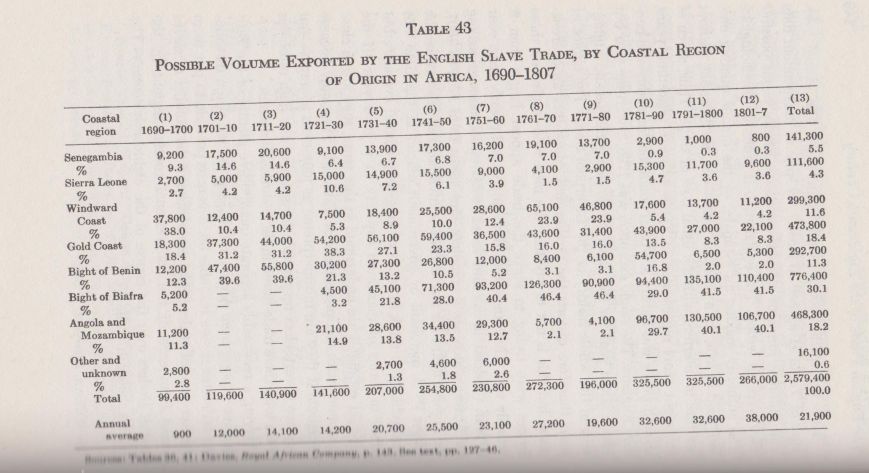

As mentioned by AncestryDNA its so-called “ethnicity estimates” might also reflect ancient migrations taking place “thousands of years ago”. This is often overlooked by people when contemplating their results. However it then of course becomes very useful to consider the current state of knowledge in regards to the earliest peopling of West Africa. Obviously this is a very complex subject and much is yet to be uncovered. Naturally I am also not claiming to be any “expert” as my own reading in this field is still limited. Therefore I will only touch on some key aspects. The quote above is taken from a rather old source and uses an outdated definition of the Kwa language group. The article itself as well as its author however remain influential and widely read. Therefore I suspect that these statements might still be essentially valid. The spread of agriculture across West Africa and its possible linkage with population migrations is not fully known in all its details yet. However it seems not farfetched to assume that especially the so-called Nok culture (within modernday Nigeria) played a pivotal role in this process.

The main driving forces behind ancient West African migrations are displayed in map 3.7. Basically two major centres of dispersal are identified, one located in modernday Nigeria and to be associated with yam cultivation and Kwa/Benue-Congo languages (the Volta-Niger grouping had yet not been proposed at that time). The other centre possibly located in modernday Mali and associated with African rice and (proto-)Mandé speakers (see this article). Migrations may have first went along the savannah corridor and only in more recent times also a southwards movement into the rainforest zone. Interestingly the Ivory Coast & Liberia seem to be exactly at the point where these two major forces meet up! Right at the intersection of so-called Lower and Upper Guinea. It might also be very insightful to know if the so-called Dahomey gap (a southern savannah enclave breaking up the West African rainforest zone) possibly played a facilitating role in these migrations taking place in the last 4 or 5 millennia.

Map 3.8 is showing the so-called Yam Belt in West Africa (see this page for a similar map). I am inclined to think that the modern-day distribution of yam cultivation could still be roughly correlated with ancient migrations within West Africa. The three world’s biggest producers are Nigeria, Ghana and Ivory Coast. Followed closely by Benin & Togo (see this article). I find it striking that this so-called Yam Belt conforms to a great part with the so-called Lower Guinea area. Which in my survey seems to be genetically defined by the interrelated regions of “Ivory Coast/Ghana”, “Benin/Togo” and “Nigeria”. It is also very fascinating to learn about the cultural significance of Yam festivals in both Nigeria, Ghana and the Ivory Coast.

Even so, obviously also ecological circumstances play a significant role in the current production of yam. And more recent historical developments as well as cultural borrowing might have altered things. For example nowadays West African populations tend to have several staple foods, incl. crops originally imported from the Americas (cassave & maize). And actually yams are also grown all the way west in Cape Verde where it still retains its original Senegambian pronounciation: inhame. Possibly derived from the Wolof verb to eat: nyami. This original form of the word yam is in fact widespread in creole or patois languages across the Afro-Diaspora in the Americas (see this article). Adding an enticing twist to this culinary saga!

Summarizing it can be said that my reasoning in this section may have been speculative in some aspects but it is still grounded in phenomena which are more or less verifiable. It might offer more clarification for my West African survey findings featured on this page. Furthermore it could explain the at first sight surprisingly frequent reporting of “Benin/Togo” and to a lesser degree also “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores among Nigerians. These could then be regarded as merely mislabeled ancestral elements native to the Nigerian genepool. In population genetics it is often the source populations which are assumed to display the greatest degree of diversity, the offshoots being a subset of this variety due to founder-effect.

Many people are still getting blindsided by AncestryDNA’s modern country name labeling. In order to get more added value from your results I find it essential to fully realize the interrelatedness of West African genetics due to ancient migrations! Currentday language families in West Africa are suggestive of these migrations but not perfectly so due to language replacement and the other reservations pointed out already above. The same goes for the distribution of Africa’s traditional native crops (yam, African rice but also Sahelian pearl millet) which again appears to be indicative for ancient West African migration patterns but understandably not correlating for the full 100%.

Unfortunately this highly fascinating topic of early West African (pre-)history is often absent or poorly represented in the curricula of primary and secondary education. Furthermore both scholars and laymen tend to pay more attention to other areas of Africa. In particular North/East Africa because of early human evolution or Ancient Egypt as well as Central/Southern Africa in regards to the Bantu expansion. Regrettably this relative neglect of West African orientated research has lead to a severe lack of basic knowledge among the general public. Leaving them vulnerable to serious misinterpretation and even at risk of being mislead by agenda-driven fringe movements.

It is a true shame that West African (pre-)history too often is forcibly linked to other faraway places simply for prestige reasons or misguided ideology. This is not to deny that West Africa has indeed been in long standing mutual contact with neighbouring parts of Africa. And these connections are certainly also research worthy. Then again so much insight is to be gained when you consider West Africa to be a regional unit within its own right and on its own terms. With its own independent historical driving forces centered principally in modern-day Mali and modern-day Nigeria along the Niger river valley, the true bearer of civilization for West Africa in so many ways.

Some suggestions for further reading:

- General History of Africa (Unesco) (all volumes online available)

- The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation (Newman, 1995)

- Themes in West Africa’s History (E.K. Akyeampong, ed., 2006)

- Celebrating Nigeria’s yummy yams (BBC, 2010)

- Lele’s Festival de ñame, 2007: 5,000 years of culinary history (Latinogenaologyandbeyond, 2017)

_______________________________________________________________________

4) West African AncestryDNA results

As far as I was able to verify all of the following screenshots below are from persons with four grandparents from said nationality, unless specified otherwise. But naturally I did not have absolute certainty in all cases. Practically all results have been collected by me from public websites or social media.2 I like to thank all my survey participants for having tested on AncestryDNA and sharing their results online so that it may benefit other people as well!

Results from Ghana

Chart 4.1 (click to enlarge)

***

Map 4.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: Abina and the Important Men

***

While reviewing the more detailed statistics I calculated for my Ghanaian sample group in chart 4.1, keep in mind that averages tend to hide underlying variation. It’s always advisable to also take into account other measures such as the median and especially the minimum & maximum values to get a sense of the range of the scores. Naturally also the sample size (mentioned in the row labeled “Number”) is essential to place this data in better perspective. And even more so actual ethnic background as demonstrated by my separate data for the few Akan and Ewe results in my survey!

We can verify that both “Ivory Coast/Ghana” (32/42) and “Benin/Togo” (9/42) appear as primary region for Ghanaians. In other words showing up with the biggest amount in a person’s breakdown. It seems that actual ethnic background within Ghana determines which one of both (closely interrelated) regions will predominate. Especially the Ewe people score high amounts for so-called “Benin/Togo”. While the so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region is much better equipped to detect Akan origins. The 4 Ga-Adangbe samples being somewhat intermediate. Obviously more samples are needed, incl. also from other Ghanaian ethnic groups. Especially samples from northern Ghana are lacking right now. While the Ashanti results are relatively well represented I do not yet have much Fante results either. But this outcome already serves as a wake-up call for people who take the country name labeling of ancestral categories as gospel 😉

Aside from “Ivory Coast/Ghana” and “Benin/Togo” also other main regions are sometimes showing up above trace level (=low confidence) in Ghanaian results. Especially “Nigeria” and “Mali”. It should be kept in mind that neither of these regions are confined to their AncestryDNA labeling. In particular so-called “Mali” might often be connected rather with northern Ghana (Gur speaking) (referred to as “Mole-Dagbani” in map 4.1). In the absence of corroborating evidence these regions are perhaps likely to suggest ancient genetic similarity. Even when in fact also relatively recent family ties to especially Nigeria might exist and be hinted at. Given the oft-mentioned traditions linking Ghana and especially the Akan to Sahelian origins, it might be surprising that the “Mali” region is not showing up more strongly among their results. However several modern researchers nowadays tend to assume these traditions are merely deriving from Akan elite connections with Mandé gold traders. Not to be generalized for the entire population which may have been native and living as (yam) farmers within current-day Ghana for a very long timespan already based on archaeological findings:

- Ethnic Politics and the Relocation of Ghana, Benin, and Mauritania (GeoCurrents, 2011)

- Les Akan: peuples et civilisations (K.R. Allou, 2015)

- ROOTS.NL (S1E2) – Searching for Gold (Tracing African Roots, 2017)

- The Akan Diaspora in the Americas (Ch. 2) ((K. Konadu, 2010)

- Toward a New Understanding of Akan Origins (A. Klein, 1996)

I will be posting these Ghanaian results grouped according to known ethnic background and ranked according to main regional score. Despite the obviously limited number of samples an insightful pattern seems to arise already. As expected “Ivory Coast/Ghana” peaks among my Akan samples. But this is not an actual confirmation of Akan lineage! The highest “Ivory Coast/Ghana” amount I have seen reported for an Akan person is 100%! However a Liberian of possibly Kru descent came very close with an amount of 97%. Also a Ga-Adangbe person reached an amount of 92% “Ivory Coast/Ghana”. So it pays to be cautious and resist jumping to conclusions.

As discussed in section 3 it seems likely that one part of the samples being used by Ancestry to determine their “Ivory Coast/Ghana” estimates are Brong, an Akan subgroup. Hence the strong genetic similarity detected with Akan persons in my survey, in particular those of Ashanti descent. For other ethnic groups in Ghana a greater variation can be expected. This does not only involve the Ewe & Ga-Adangbe from the southeast but also other ethnic groups from further north. Map 4.1 shows the main ethnolinguistic groups living in Ghana. For even greater detail you may also want to consult this one.

***

GHANA (Akan)

***

***

The so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region is capable of providing very accurate predictions of Akan ancestry. This is convincingly demonstrated in the screenshot above and also the following ones. This person of Akan background is being described as practically 100% “Ivory Coast/Ghana” if you ignore the miniscule trace regions. Which is just what you would expect, even when such genetic statements are usually more complicated. In this case it was probably a near perfect match to AncestryDNA’s samples from Ghana which led to this outcome.

***

GHANA (Akan:Ashanti)

***

***

GHANA (Akan: Ashanti)

***

***

GHANA (Akan)

***

***

GHANA (Akan: Ashanti & Sefwe)

***

***

GHANA (Akan: Ashanti?)

***

***

GHANA (Akan: Ashanti)

***

***

GHANA (Akan: Ashanti & Brong-Ahafo)

***

Interestingly a considerable “Mali” score appearing above trace level for this person of partial Brong descent. However during my survey such scores have been uncommon for my Akan survey participants.

***

***

GHANA (Akan?)

***

I have no complete certainty about this person’s background so I suppose that actual distant Nigerian lineage (going back 3 or 4 generations) could indeed be a possibility. As suggested by the 9% “Nigeria” amount. Especially Hausa and Yoruba migrations into Ghana are known to have taken place already long before its independence in 1957. However I suppose it might also simply indicate genetic similarity caused by ancient migrations and shared origins across Lower Guinea.

- Nigerians in Accra: Their stories and successes (Daily Trust, 2017)

***

***

GHANA (Akan?)

***

***

GHANA (Akan: Fante, only 1/2?)

***

This is one of possibly 4 results with a Fante background in my survey. It was only confirmed for one side though so maybe this person’s other parent is of another background. Explaining perhaps the increase in “Benin/Togo”. But who knows perhaps also persons of fully Fante background might get described this way. Afterall their southern location might imply some genetical differentiation when compared with Akan speakers from further north, such as the Ashanti and Brong.

***

***

GHANA (1/2 Akuapem & 1/2 Fante)

***

The Akuapem are an interesting group. Despite being Akan speakers they are said to be a fairly recent “amalgamation of indigenous patriarchal, Volta-Camoe-speaking Guans and matriarchal, Kwa-speaking Akan people“. The Guan people being assumed to have been among the earliest settlers of Ghana! Interestingly the breakdown turned out to be quite balanced also.

- AKUAPEM PEOPLE: GHANA`S ANCIENT GUANS AND AKANS OF THE MOUNTAINS (Trip Down Memory Lane 2013)

***

***

GHANA (1/2 Akuapem & 1/2 Gbe: Ewe)

***

A similar breakdown as the previous one. As will be seen further below the increased “Benin/Togo” amount might also be correlated with this person’s partial Ewe lineage.

***

***

GHANA (3/4 Akan & 1/4 Gur: Frafra)

***

This breakdown could easily be mistaken for one of the results I have seen for people of fully Akan descent. But still this person is aware of atleast one Gur speaking (Frafra) grandparent from Bolgatanga, all the way north. Otherwise one parent selfidentifes as Ashanti and another grandparent would be Fante. Interestingly the so-called “Mali” amount is hardly detectable beyond a slight trace amount.

- Frafra people (Trip Down Memory Lane, 2013)

***

***

GHANA (Akan & Ga-Adangbe)

***

Eventhough belonging to an ethnically mixed person this breakdown is still showing a very convincing “Ivory Coast/Ghana” score. Based on their geographical location as well as their language not being categorized as Gbe it might already be assumed that generally speaking the Ga-Adangbe will be genetically close to the Akan. However given their internal sub-groups and possible inter-ethnic unions from several generations ago with the neighbouring Ewe people undoubtedly there will be greater variation.

***

***

GHANA (Ga-Adangbe)

***

This insightful breakdown provides proof that high “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores are not exclusive to Akan results. Also interesting to see the 6% “Nigeria” showing up. Even when several scenarios might apply, it’s still intriguing to know that the Ga people (similar to the Ewe) have oral traditions about migrating from southern Nigeria in the last millennium when the famous Benin empire was expanding.

- Origin of the Ga-speaking people of Accra (Watson-Quartey, 2011 / Trip Down Memory Lane, 2013)

The DNA results for this person and the two following Ga-Adangbe persons have been enabled by the very laudable “African Royal DNA Project”.

Its mission is to:

“assist Africans in the Diaspora whose ancestors were forcefully removed from the Continent an opportunity to find their actual biological families. The project also allows the African Royals on the Continent to find out what happened to their families that were taken. “

For more details see their websites:

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

GHANA (Ga-Adangbe)

***

Again very insightful breakdown as it features one of the highest so-called “Mali” amounts reported for a Ghanaian in my survey. Several possible explanations might apply. It would have been interesting to see how typical such a score might be with the addition of more Ga-Adangbe results in my survey.

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

GHANA (Ga-Adangbe: Krobo)

***

Very educational to see these results which look quite different from the two directly above. Highlighting the variation among Ga-Adangbe people. The Krobo being a sub-group which is well known for its cultural traditions. In accordance with the elevated level of “Benin/Togo” shown below one of their probable source of origin is stated to be Sameh in either Benin or Nigeria.

- Krobo people (Trip Down Memory Lane, 2012)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

GHANA (no further details)

***

***

GHANA (Gur: Champa, possibly distant Hausa)

***

The screenshot below features one of the most evenly divided breakdowns in my Ghanaian survey. With no less than 4 main regions being mentioned, very atypical up to now. Usually the top 2 regions combined are clearly predominant for Ghanaians (>90%). This higher regional concentration being a key aspect to distinguish native African results from those of the Afro-Diaspora, generally speaking (see this overview). Evenso all 4 main regions are still plausible for the Ghanaian context.

Intriguingly these results belong to a person with confirmed origins from northern Ghana. One parent self-identifying as Chamba which is a subgroup of the Konkomba people who are Gur speakers. They have a highly interesting history as it is said they are among the oldest known inhabitants of northern Ghana. Unfortunately their past also includes recurrent conflict with neighbouring ethnic groups. For Afro-descendants in the Americas it is extremely useful to be aware that “Chamba” was also a frequently used ethnonym for enslaved captives in the West Indies!

Also noteworthy is that this person’s family is Hausa-speaking. Actually Hausa is a commonly used lingua franca in northern Ghana, due to its trading diaspora. So actual Hausa descent is not required to be a Hausa speaker in Ghana. But still given the rather elevated “”Nigeria” amount (the second-highest score in my survey) it could be indicative of genuine Hausa lineage I suppose. I was kindly granted access to this person’s DNA matches. And by using my filtering tutorial I was able to find at least 2 matches who seem to be from northern Nigeria (both family names & ethnic regions being plausible). Nothing conclusive as actually the geneflow might also be the other way around, but still a very neat finding!

See also:

- Konkomba, History, Culture, Religion, Economy (M. Herbstein, 2006)

- The Konkomba people (Trip Down Memory Lane, 2013)

- An Historical and Ethnographic Commentary on The Northern Conflict (Katanga, 1994)

- Chart featuring the ethnic origins of runaway slaves in Jamaica, incl. 169 Chamba! (D. Chambers, 2007)

- History of Hausa in Ghana (Zango FM)

***

***

GHANA (Gur & Akan: Mamprusi, Mossi & Fante)

***

Again quite exceptional breakdown. Not only because it features so many different regions. With “Ivory Coast/Ghana” almost ending in last place! But in particular because of the primary score of “Mali”. Very insightful outcome! As I have always suspected from the start that “Mali” might be indicative not only of Mande speaking origins from Upper Guinea but also of Gur speaking origins from Burkina Faso (such as Mossi) and surrounding areas, incl. northern Ghana (such as Mamprusi)! Given this persons mixed ethnic background the other remaining scores could have several explanations.

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

GHANA (Gbe: Ewe)

***

This person of confirmed Ewe background on all lines is being described as practically 100% “Benin/Togo” if you ignore the minuscule Trace regions. It is therefore a very insightful even if perhaps counter-intuitive breakdown for a Ghanaian person. It is by far the highest “Benin/Togo” score I have seen in my survey up till now. The circumstance that “Benin/Togo” seems to be especially peaking for persons of Ewe background is very much suggestive of Ancestry using Gbe samples to calculate their so-called “Benin/Togo” estimates. Not only from Benin but possibly also including actual Ewe samples from Togo! After all that would explain this nearly perfect match to the samples in Ancestry’s database. Interpreted in such a manner this breakdown is actually very coherent!

This outcome also makes for a perfect example to illustrate how the country name labeling by AncestryDNA should not be taken as gospel. Almost all African countries have been colonial creations with borders cutting right through the homelands of ethnic groups. Also very closely related ethnic groups can often be found on both sides of the border. This is indeed the case for the Ewe people and the greater language group of the Gbe they belong to. And especially Togo has very artificially drawn borders. The split-up of Eweland being caused by the takeover of formerly German held colony of Togoland.

- Is “Benin/Togo” really pinpointing origins from within Benin’s borders?

- British Togoland (wikipedia)

- Map of Eweland

***

***

GHANA (Gbe: Ewe)

***

***

GHANA (Gbe: Ewe )

***

***

GHANA (Gbe: Ewe )

***

***

The results above belong to a person who self-identifies as being Ewe. It appears therefore that the “Benin/Togo” amount will show some significant variance for Ewe results (97%-72%-46%), perhaps correlating with deeper ancestry or also with more recent inter-ethnic unions from only a few generations ago. I will need more Ewe survey participants to confirm. But it can already be said that 9% “Cameroon/Congo” does seem very atypical. It is not showing up as a low confidence region. Which increases the odds that this is a genuine finding of probably Central African DNA! I have yet to see such a relatively high amount being reported for Ghanaians or other West Africans, with the exception of Nigerians but in their case it’s plausible given that Cameroon is their neighbouring country.

I am merely speculating here, but generally speaking I would assume that such a surprising instance of seemingly Central African DNA is possibly to be linked to the return movement of formerly enslaved persons from the Americas. Not only from the US or the West Indies but also in fact from Brazil! Accra is still home to the so-called Tabom people for example. These people are often assumed to have been especially of Yoruba descent but perhaps some of them already had multigenerational roots in Brazil and would therefore also be multi-ethnic, incl. some Angolan or Congolese mixed in. Otherwise it might also be due to Congolese Recaptives, although I have only read about them being brought to Sierra Leone and Liberia. However the Krio people from Sierra Leone in turn did migrate to other West African cities, incl. Accra. I suppose actual DNA matches from either these last two countries or more spectacularly from Central Africa itself might offer more clarification. For more details:

- Afro-Brazilians in Ghana (Tabom) (Wikipedia)

- A Slice of Brazil In Accra (Modern Ghana, 2011)

- Historia dos Tabom, Afro-Brasileiros em Acra, Gana (A. Meira Amos & E. Ayesu, 2005)

- Presence of Krio in Accra (Dakubu, 1997)

***

GHANA (Gbe: Ewe & Akan: Fante)

***

Almost 50/50 breakdown with “Benin/Togo” surpassing “Ivory Coast/Ghana” but not by that much. Seems like a fitting outcome for this person with both Ewe and Akan lineage.

***

_______________________________________________________________________

Results from Benin

Chart 4.2 (click to enlarge)

Map 4.2 (click to enlarge)

***

For a long time I could not include any results from Benin in my survey. This is most likely because migrants from Benin are quite uncommon in the US or the UK. And therefore they will appear less frequently within AncestryDNA’s customer database than for example Nigerians or Ghanaians. However in 2018 I was very lucky to add a substantial number to my Beninese survey group (n=9). This addition was enabled by the commendable “African Royal DNA Project”. When it comes to my West African survey results I am very much indebted to this pioneering and powerful project!

Its mission:

“assist Africans in the Diaspora whose ancestors were forcefully removed from the Continent an opportunity to find their actual biological families. The project also allows the African Royals on the Continent to find out what happened to their families that were taken. “

For more details see their websites:

- https://www.dnatestedafricans.org

- http://www.rootstoglory.com

- An Amazing Success Story of DNA Testing and a Benin Reconnection !

Except for one person all my 9 Beninese survey participants are Gbe-speakers. And it turns out that the so-called “Benin/Togo” is indeed quite predictive of genuine Beninese DNA. Their “Benin/Togo” scores (70% on average and with a 79% median, see chart 4.2) are in line with what Ancestry mentions about the score of the “typical native” being 82%! Still also minor but considerable scores of “Nigeria” as well as “Ivory Coast/Ghana” are on display for some individuals.

As discussed in section 3 it seems likely that the samples being used by Ancestry to determine any “Benin/Togo” score are from either southern Benin or southern Togo and belong to a Gbe (Kwa) speaking subgroup. For other ethnic groups (non-Gbe) in Benin a greater variation can be expected. For some groups “Benin/Togo” might then actually only be secondary or even very minor when compared with more prominent scores for either “Nigeria” (Yoruba), “Mali” (Bariba and other Gur-speaking) or even “Senegal” (Fula/Fulfulde). Map 4.2 shows the main ethnic groups living in Benin. Or see also this one which is even more detailed. For further reading:

***

BENIN (Gbe: Ayizo)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

BENIN (Gbe: Ayizo)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

Both of these results belong to persons who are from the Ayizo People of Dahomey Kingdom in Allada, Benin. They were made available by the praiseworthy efforts of the African Royal DNA project. A true blessing because as already described above it doesn’t seem likely many other DNA testers from Benin will be forthcoming. Even when Benin holds a tremendous significance for the Afro-Diaspora.

- Royal DNA Results Are In for Benin (Dahomey Kingdom) (African Royal DNA Project, 2017)

Overall speaking these two results seem perfectly in line with their known backgrounds. The Ayizo language belonging to the Gbe language group, just like Ewe and Fon. The minor regional scores for so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” and “Nigeria” being consistent with inevitable genetic overlap. However it might be educational to indulge in some speculation concerning the seemingly Central African trace regions (4% “Cameroon/Congo” and 3% “Southeastern Bantu”) shown in the second screenshot. They could very well just be a mere misreading of DNA patches which Ancestry finds hard to classify (hence “low confidence”!). So it might not be relevant for the person in question. But generally speaking I suppose such amounts could also *possibly* be explained by distant Aguda ancestry: formerly enslaved Afro-Brazilians who returned to West Africa in the 1800’s. Adding an intriguing but complicating twist when wanting to interpret DNA results from southern Benin. But also in fact Togo, Ghana and Nigeria.

- Afro-Brazilians in Benin (Aguda) (Orisha Image, 2017)

- Afro-Brazilians in Togo (A.M. Amos, 2001)

- Family of Souza of Benin & Togo (S. de Souza, 2005)

- “Letters from Africa”: The Diaspora of the Diaspora (C. Fonseca, 2001)

***

BENIN (Gbe: Gun/Goun)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

The results above as well as the following ones all belong to people of the Gun or Goun kingdom around the Beninese capital of Porto Novo. The Gun language they speak belongs to the Gbe language family. Some of the results show an impressive “Benin/Togo” level while others are more varied. Given the location and its historical connections with the Yoruba and people to the west (perhaps also the Mina people?) not that surprising. For more info:

- Chronologie du royaume gun de Hogbonu (Porto-Novo) (1975)

- Youtube video of Gungbe speaker

- Youtube video of African American being reunited with his Benin DNA cousin

BENIN (Gbe: Gun/Goun)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

BENIN (Gbe: Gun/Goun)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

BENIN (Gbe: Gun/Goun)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

BENIN (Gbe: Gun/Goun)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

BENIN (Dendi)

***

Source: African Royal DNA Project

***

Very special results as the Dendi people are quite unique! As can be seen in map 4.2 they are located all the way in the north of the country, along the border with Niger. Where the closely related Songhay people live. Linked to the famous Songhay empire therefore! Their Dendi language is also quite singular in not only Benin but the whole of West Africa because it is often classified as belonging to the Nilo-Saharan language family. Which could be testament to ancient migrations along the Sahelian corridor.

The African breakdown on display is one of the most evenly mixed among my Benin survey group. Most likely because their DNA is not easily described by the given categories. But what really stands out is the elevated “Mali” score. Indicative of genetic affiliations with people from the West African interior. As also seen for Gur speaking results from Burkina Faso and people from the northern parts of Ivory Coast and Ghana.

- Songhay Empire (Wikipedia)

_______________________________________________________________________

Results from Liberia

Chart 4.3 (click to enlarge)

***

Map 4.3 (click to enlarge)

Source: Ethnologue

***

While reviewing the more detailed statistics I calculated for my Liberian sample group in chart 4.3, keep in mind that averages tend to hide underlying variation. It is always advisable to also take into account other measures such as the median and especially the minimum & maximum values to get a sense of the range of the scores. Naturally also the sample size (mentioned in the row labeled “Number”) is essential to place this data in better perspective. And even more so actual ethnic background!

During my survey it turned out that by far “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is the most characteristic AncestryDNA region appearing for Liberians. Generally speaking and usually also convincingly so (see median score). However this is almost always combined with other main regions showing up. In particular “Senegal”, “Mali”, and “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers”. “Senegal ” being the most important secondary region. It should be kept in mind that none of these regions are confined to their AncestryDNA labeling.

I have ranked these Liberian results based on the amount of highest to lowest score for “Ivory Coast/Ghana”. And despite the obviously limited number of samples an insightful pattern seems to arise already: “Ivory Coast/Ghana” peaks among Liberians with a Kru background. But it is not an actual confirmation of Kru lineage! A complicating factor in my Liberian survey is that most of my survey participants have a mixed ethnic background (within Liberia). More results of Liberians with just one single ethnic background (at least for all 4 grandparents) would be needed to get a clearer picture. The highest “Ivory Coast/Ghana” amount I have seen reported for a confirmed Kru (Grebo) person is 94%. But I strongly suspect that an even higher score of 97% also belongs to a person of Kru descent. A shocking outcome perhaps for people who still take the country name labeling on AncestryDNA too literally 😉 But it actually does make sense if you are aware of the full context.

As discussed in section 3 it seems reasonable to assume that Ancestry not only uses Brong samples from Ghana to determine their “Ivory Coast/Ghana” estimates. But in addition it might also be using both Kru samples and southern Mandé samples from Ivory Coast. Both of these language groups are also represented by closely related ethnic groups in Liberia! So this could very well explain the strong genetic similarity detected with especially Liberian Kru persons. Furthermore it might also be the reason for the still relatively high “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores being reported for people of southwest Mandé background in Liberia, such as the Kpelle and the Dan/Gio. Again I will need more (unmixed) samples to confirm though.

The only Liberians with decreased “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores (<50%) in my survey seem to be Liberians with a background which includes ethnic groups living right next to the border with either Sierra Leone or Guinea, such as the Vai and Gbandi. Regrettably I have no full details for the only Liberian to score “Senegal” as a primary region rather than “Ivory Coast /Ghana”. Either way it seems that a greater variation is possibly to be expected for selected ethnic groups in the north. This is however only intended as a tentative statement! It might be particularly insightful to know the results of a person of fully Gola descent. As the Gola language is considered an isolate and the only language within Liberia (along with Kissi) to be grouped within the Atlantic language family (see map 4.3). The consistency of the minor but still distinctive “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” region among my Liberian sample group has been another very fascinating finding. As it seems to confirm the mythical tales about the very first inhabitants of Liberia! For more details see:

Further reading:

- Liberians: An Introduction to their History and Culture (ed. D. Renard, 2005)

- Overview of Liberian ethnic groups (incl. proportions) (CEFAN, 2015)

- The People Groups of Liberia (H. Vogel, 2012)

- The Grain Coast, Malaguetta Coast or Pepper Coast before 1822 (Liberia: Past & Present)

***

LIBERIA (Kru?)

***

***

Despite the perhaps confusing labeling the so-called “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region seems to be strongly corresponding with Liberian ancestry. At least for Liberians themselves. This is convincingly demonstrated in the screenshot above and also the following ones. Suggesting a near perfect match to the samples contained in Ancestry’s Reference Panel, which are being used to calculate their “Ivory Coast/Ghana” estimates. A fully 100% amount could have been achieved had it not been for the 3% “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” score. As will be seen in the following screenshots such minor but still clearly detectable amounts are very consistent and typical for Liberian results in my survey.

Because the person behind these results was adopted I regrettably do not have any further details about her background. However I suspect that she could very well be Kru and in particular Krahn, as they may have been the most relatively numerous among the refugees of the immensely tragic Liberian civil war. Either way it is very telling that both a Liberian and a Ghanaian person obtained a 97% “Ivory Coast/Ghana” score. As this is bound to have implications for how Afro-Diasporans should interpret their own so-called “Ivory/Coast/Ghana” scores. I will provide more details in the next section. However right now it might already be useful to point out that this person is part of the so-called “African Caribbean” genetic community (labeled as “migrations”) based on a shared genetic affiliation for “Ivory Coast/Ghana”. I was kindly given permission to view this person’s DNA matches and she has no less than 1,540 matches (30 pages)! Practically all of them either African Americans, Hispanics or West Indians.

***

LIBERIA (Kru: Grebo)

***

***

These results belong to a woman of confirmed Kru descent. Her testresults are also shown in a great Youtube video. It can be seen further below in the video section or by following this link. The remaining amount not shown in the screenshot is 2% “Senegal”. I need more results to confirm but such a breakdown might be quite typical for people who are solely of Kru descent.

***

LIBERIA (Kru & Mandé: Kpelle)

***

***

These results belong to a man of a mixed Kru and Kpelle background. His testresults are also shown in a great Youtube video. It can be seen further below in the video section or by following this link. It might be deemed surprising that his partial Mandé lineage (Kpelle) did not result in higher “Mali” and/or “Senegal” amounts. As it is right now they are both merely reported as trace regions of 2%. While “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is shown convincingly as the predominant region. Due to a lacking number of Liberian results to compare with I can only speculate at this moment. However I would venture to say that *possibly* this outcome is caused by an (assumed) inclusion of Ivorian Mandé samples by AncestryDNA. Again I would need to get more confirmation, however it might explain why both this person’s Kru and Mandé side are described as overwhelmingly “Ivory Coast/Ghana”.

A complicating factor would be that despite being Mandé speaking it could actually be that the Kpelle people during their migrations into Liberia might have absorbed people of other ethnic groups into their ranks, either by cultural assimilation, language shift and/or also inter-ethnic marriages. Another perhaps relevant aspect would be that the Kpelle language is classified as being a southwestern Mandé language, at times also termed “Mandé-Fu”. Despite commonalities this separates the Kpelle language from the so-called Mandé-Tan or also Manding languages which are more commonly associated with the former Mali empire. See also:

***

LIBERIA (Kru: Grebo & Lofa county)

***

***

LIBERIA (Kru: Grebo, Mandé: Kpelle, Atlantic: Gola, and distant “Congo”)

***

***

This breakdown belongs to a person with a rather mixed background. Yet still his primary “Ivory Coast/Ghana” score seems very prominent. Interestingly there is awareness of one distant ancestor (great-grandparent) with repatriated slave heritage, sometimes also known as “Congo” in Liberia. Similar to Sierra Leone also in Liberia many so-called recaptives were brought in for settlement. Apparently because many of these liberated Africans happened to be from slaveships intercepted near the Congo river they were all called “Congo” irrespective of actual provenance. At first a distinction was made between them and the Americo-Liberians, who were rather formerly enslaved persons from the USA. However, over the years the two groups joined and now it seems that the terms “Americo-Liberian” and “Congo” are used interchangeably. Very similar to the formation of the Sierra Leone Krio people. Except that the Liberian term “Congo” seems quite misleading for the much more intricate and varied origins of the Americo-Liberians.

During my survey I have been very careful to seek out any clues of Americo-Liberian lineage as understandably this might complicate a proper interpretation given their rather mixed origins. Despite being very influential they have afterall always been a small minority. According to some estimates about 2.5% of the total population. I am merely speculating here but in this case perhaps the 4% “Nigeria” as well as the 2% “Southeastern Bantu” score might be associated with this person’s Americo-Liberian familyline. However only DNA matches might confirm I suppose.

***

LIBERIA (Kru)

***

***

This person might yet be of an ethnically mixed background, involving also neighbouring Guinea. But there is no certainty about it. Either way the breakdown seems pretty much in line with those of other Kru persons I have seen up till now. The 6% so-called “South-Central Hunter-Gatherer’s” amount is the highest I have seen in my survey. Another Liberian received the same score. As mentioned already a possible connection with Liberia’s earliest inhabitants seems very tempting. I should point out that I did not come across any apparent hint of “Congo” lineage for this person, which might theoretically provide another explanation for the elevated 6% “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” score.

***

LIBERIA (?)

***

***

LIBERIA (Mandé: Dan/Gio)

***

***

This person’s family is from a Mandé speaking ethnicity called either Dan or Gio. They are located in the border area with Ivory Coast and Guinea Conakry (see map 4.3). Interestingly only 17% of his ancestry is designated as “Mali” while “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is clearly prevailing. As mentioned for the half Kpelle result above *possibly* this outcome is caused by an (assumed) inclusion of Ivorian Mandé samples by AncestryDNA. Perhaps these samples might even belong to the same Dan ethnic group, as they are found across the border as well. And apparently an alternate name of theirs is Yacouba! More results from Mandé speaking Liberians and Ivorians are needed to confirm though.

Even though the 17% “Mali” score might seem minor, it is still showing up quite strongly when we take into account that 1) a “typical native” of Mali is only 39% “Malian” according to Ancestry (see also AncestryDNA Regions) 2) the Liberian group average for “Mali” is 7.6% (n=12). So eventhough it shows up relatively subdued, “Mali” might yet be a significant ethnic marker for this Liberian person.

Still it is also intriguing to speculate what this may imply for the deeper ancestral origins of Mandé speaking groups in Liberia. It is known historically they were last to arrive in Liberia (Atlantic/Mel speaking groups being assumed to have settled first followed by Kru speakers from the east, see also this link). And they might have absorbed many previous inhabitants among their ranks by intermarriage and/or language shift. The Dan/Gio language is being classified as a southeastern Mandé version. Sharing many commonalities with the central and more “classic” Mandé languages but still also separate. Implying different historical and possibly also different genetical trajectories. Again I will need more samples to confirm though. A perhaps hardly noticeable hint but still meaningful could be the trace amount of <1% for “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers”. This is the lowest amount I have observed for Liberians and might suggest a minimal intermingling with strictly coastal populations.

***

LIBERIA (1/2 Kru: Bassa & ?)

***

***

I have only full confirmation for one side of this person’s family. This person might yet be of an ethnically mixed background, incl. also distant Americo-Liberian. But there is no certainty about it. Either way the breakdown seems pretty much in line with those of other Kru persons I have seen up till now. Except perhaps for the 4% “Southeastern Bantu”. Which is the third-highest such score I have observed for Liberians.

***

LIBERIA (no further details)

***

***

Regrettably no further details available for this persons background. However all the main regions seem perfectly in line with what I have observed during this survey. Except that the 6% “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” is very distinctive. The highest such score for Liberians up till now.

***

LIBERIA (1/2 Kru: Grebo & 1/2 Mandé: Vai)

***

***

LIBERIA (?)

***

***

LIBERIA (Mandé: Vai, Gbandi & Kru: Bassa & distant West Indian)

***

***

Yet again a person of quite mixed origins (within Liberia). However for the first time we can see how “Ivory Coast/Ghana” can also be relatively low (<50%) for Liberians. Both “Senegal” and “Mali” amounts are above group average. With especially the “Mali” score standing out! It seems very likely that this outcome is correlating with her partial Mandé side (Vai & Gbandi). As her confirmed Kru lineage (Bassa) would only apply for one grandparent. Interestingly unlike the Gbandi language and most other Liberian Mandé languages the Vai language is classified as being similar to the central versions, incl. Manding. It would be very insightful to compare with the results for a person of fully Vai descent.

The great-aunts of this person’s grandfather are said to have been formerly enslaved West Indians. This might appear to be quite distant but still would account for a sizeable degree of Americo-Liberian lineage (1/16?). The strikingly elevated scores for “Cameroon/Congo and “Southeastern Bantu” already seem quite suggestive as combined they are the highest such scores I have observed for Liberians. Despite being “low confidence” regions at this increased level the possibility of minor Central African DNA seems quite realistic.

Intriguingly the trace amount of European admixture also seems very indicative of such a heritage. It is showing up as <1% so-called “Iberian Peninsula” which in itself is not to be taken too literally. It could be a misreading of other types of western or also southern European DNA. And actually even North African DNA is often described by this category. Which sometimes results in minor scores of this region being reported for Fula people! Given the various possibilities it will be very instructive to have a closer look into the DNA matches.

I was kindly granted access to this person’s DNA matches. I first scanned all of them and then I filtered them for both 100% African as well as 100% European profiles (see this tutorial). Amazingly out of a total of 3,372 DNA matches (68 pages!) it seems that she has over 500 European-American matches! Some of them with also quite large shared DNA segments (around 20cM). Now it might be that actually in some cases there might be some hick up in Ancestry’s algorithm and these matches in fact are not 100% European genetically speaking. Sometimes due to privacy settings Ancestry does not display all of the ethnic regions for your matches. Which could imply that it’s them who would have some distant African ancestor rather than the other way around. Still I think the odds are high that she indeed has some distant European ancestor by way of the West Indies. Looking at the African matches, (possibly about 17), most of them seem to be from Liberia as expected. This is going by plausible family names as well as ethnic regions. Also a few matches could be from Sierra Leone and Guinea. Interestingly two profiles might be be partially Senegalese and one match might be Nigerian! Again possibly an indication of distant West Indian lineage.

***

LIBERIA (Mandé: 1/2 Kpelle & ?)

***

***

Unfortunately I have no full details about this person’s background. Except that one side of her family would be Kpelle. However just like the previous breakdown again “Ivory Coast/Ghana” is quite subdued while “Mali” and especially “Senegal” are showing up very strongly. Another noteworthy aspect of this breakdown would be the 8% “Cameroon/Congo”, the highest such score I have seen in my Liberian survey. Possibly together with the 4% “Nigeria” it might be indicative of distant Americo-Liberian ancestry. I can only speculate in regards to the other half of this person’s background but I suspect that another Mandé line could very well be included as well.

***

LIBERIA (northern?)

***

***