Map showing all the regions available on Ancestry after its 2019 update. For Trans Atlantic Afro-descendants the most impactful changes seem to be that: “Nigeria” has been brought back to life again! But “Ghana” has been derailed. “Mali” is no longer overpowering “Senegal”, but it does include both Sierra Leone and Liberia now! See this link for a complete list of regions and genetic communities. Photo credits for top picture showing a train passing by a railway station in Ghana.

***

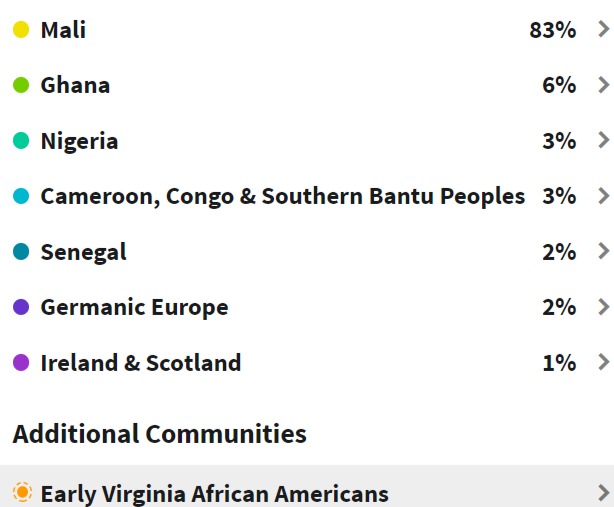

Starting in October 2019 Ancestry has been rolling out a new update of their Ethnicity Estimates. As I have said before your DNA results are only as good as the next update. So it is best not to get too attached to them 😉 Given scientific advancements and a greater number of relevant reference samples one always hopes that a greater degree of accuracy may be obtained. But naturally no guarantees are given that this will indeed be the case. After all Ancestry’s update in 2018 arguably was a downgrade rather than providing any meaningful improvement! At least when it comes to the African breakdown. In regards to the European, Asian and Amerindian breakdown Ancestry seems to have made steady progress on most fronts. Continued also with this 2019 update.

From my experience the best indication of predictive accuracy is obtained by looking at how Africans themselves are being described when tested by Ancestry. Which is why I have performed a comprehensive survey among 136 African Ancestry testers from all over the continent to establish a more solid basis for judgement. In addition I have also looked into a representative array of 55 updated results from across the Afro-Diaspora. These findings will be described in greater detail further below. The outcomes are mostly positive for Africans themselves but more ambivalent for Afro-descendants. Probably because Ancestry’s algorithm is less adequate when describing the mixed and therefore more complex African lineage of the Afro-Diaspora. My overall verdict about this 2019 update: a step in the right direction but no substantial improvements for the most part. At least not when compared with the original African breakdown from the 2013-2018 version.

***

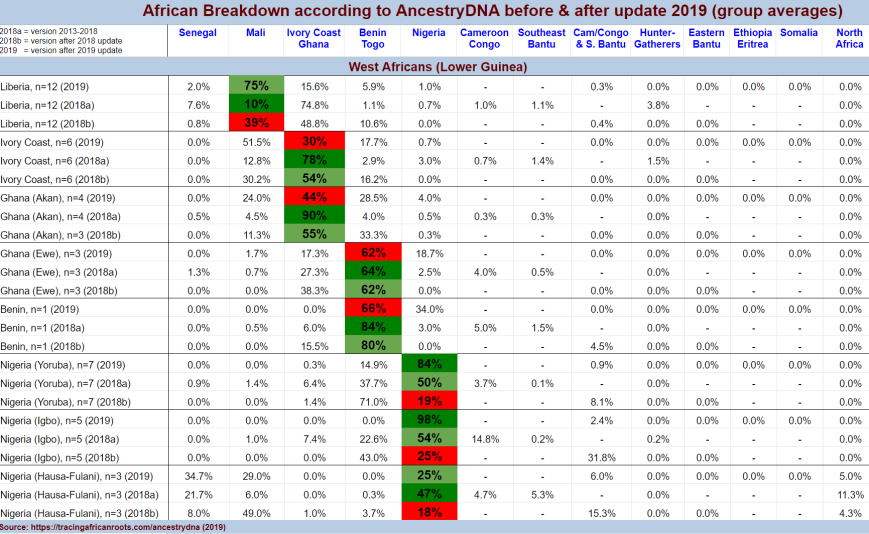

Table 1 (click to enlarge)

Based on the updated results for 121 African AncestryDNA testers from 30 countries, across the continent. Take notice that the predictive accuracy in most cases is quite solid. Although in a few cases it is still clearly in need of improvement. This goes especially for “Ghana” and “Eastern Bantu”. Follow this link for my spreadsheet containing all the individual results.

***

Due to wild fluctuations in just two years many people might experience update fatigue. Some people will even be tempted to bash their DNA test results and admixture analysis in particular. But an overtly dismissive stance will be self-defeating and deprive you of informational value yet to be gained! As I have always argued that regional admixture DOES matter and Ancestry’s Ethnicity Estimates are of course NOT randomly determined.1 Ancestry’s predictions may not be 100% accurate but still in most cases they are reasonably well-aligned with the known backgrounds of my African survey participants. As can be verified from the overview above.

For those perplexed by all the changes do at least make an attempt to inform your self properly. Given how wrong Ancestry got it in 2018 (see this blog series) it is only natural that some grave flaws had to be rectified. Regrettably it seems in some aspects an over-correction did take place. Still depending on your background this update certainly also can be beneficial. Furthermore when considering your African breakdown in a macro-regional framework the changes have actually not been that drastic. And many things more or less remained consistent as I will discuss in section 3 of this blog post.

It has always been my belief that regional estimates require correct interpretation. And each updated version as well as each separate DNA testing company should therefore be judged on its own terms. Then again these admixture results can only take you that far. My advise is to also look into your African DNA matches, as well as historical plausibility and just plain genetic genealogy for greater combined insight. See also these links:

- Ethnicity Update FAQ (Ancestry)

- How to deal with updated DNA test results

- How to find those elusive African DNA matches on Ancestry

- African DNA Matches Service

For those seeking deeper understanding of Ancestry’s 2019 update this blog post will attempt to take things further by having a closer look at:

- African breakdown for Africans before and after the 2019 update

- Ancestry’s Reference Panel & Algorithm

- African breakdown for Afro-descendants before and after the 2019 update

- Getting back on track again

- Screenshots of African updated results

- Poll on whether this update has been an improvement or not, please vote!

***

1) African breakdown for African AncestryDNA testers

As can be seen in table 1 above Ancestry’s regional framework seems to be reasonably coherent for Africans. This can be verified from the group averages for the expected primary regions usually being rather convincing (>65%). And one can also notice how each region only gets reported in substantial amounts (>5%) in the expected broader macro-regions of Africa. For example “Senegal” is usually at 0% outside of West Africa. Only showing up outside of Upper Guinea due to Fula migrations into Nigeria and beyond. And “Cameroon, Congo & Southern Bantu” is usually around 0% inside of West Africa. Even in southeast Nigeria there is hardly any intrusion any more (as was the case after the 2018 update).

Ancestry’s 2019 update has expanded the African breakdown with 2 new regions: “Ethiopia & Eritrea” and “Somalia”. The total number of African regions now being eleven. Otherwise only a few cosmetic name changes have taken place except for the rearrangement of the former “Ivory Coast & Ghana” region into just “Ghana”. This change most likely involved the removal of Ivorian samples and has had a rather great impact. Regrettably not for the better though… As will be described in more detail below and following sections. As a consequence “Mali” now also explicitly includes Sierra Leone, Liberia and to a lesser degree the Ivory Coast (see this map).

In this section I will perform a before & after analysis of 121 AncestryDNA results of African customers from across the continent.2 This seems like a reasonably robust number and a wide enough array to pick up on some preliminary patterns. Even when for most of the separate nationalities I was only able to obtain a minimal sample size. Obviously these findings are not intended to reflect any fictional national or ethnic averages! The main purpose of this overview is to give an approximate idea of what to expect when wondering about how AncestryDNA’s update has affected the results of African customers. It is admittedly much to take in and therefore I will only focus on the main changes for each part of the continent. For a similar discussion based on the 2018 update see this blog post:

In the tables below the group averages are shown according to Ancestry’s 3 versions:

- 2018a = Ancestry’s original African breakdown as reported from 2013-2018.

- 2018b = updated version after Ancestry’s update in September 2018.

- 2019 = latest version which emerged after the 2019 update.

In most cases the informational value to be derived from these results seems to show improvement. But not always. The most accurate/useful version has been marked in dark green. According to my own personal judgement/preference of course 😉 . But mostly based on the criterium of highest group average conforming with expected primary region (also taking into the account the wider regional description given by Ancestry). The second-best version will be marked in light green. While the least informational version will be marked in red. Usually this version would be a clear downgrade in my opinion but in a few cases some redeeming aspects might still be present.

Follow the link below for my online spreadsheet which contains all the individual results, before and after each update. It also includes group averages for other continental scores (West Asia, Asia & Pacific, Europe):

West Africans (Upper Guinea)

Figure 1.1 (click to enlarge)

Also in 2020 the motto remains: don’t take the country name labeling too literally! Remember they are only meant as indicative proxies. However if you take into account neighbouring countries as well as look into the regional maps provided by Ancestry you will gain greater understanding of your results

***

Table 1.1 (click to enlarge)

***

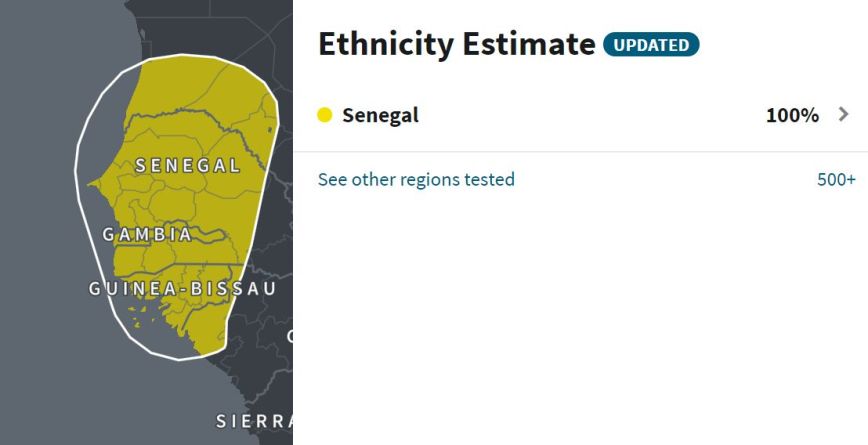

- The “Senegal” region has recovered and even improved on its predictive accuracy. The inappropriately high “Mali” scores for Senegambians, Fula and Cape Verdeans from the 2018 update have mostly vanished.3 Interestingly my single survey participant from Guiné Bissau (Fulakunda) received a more balanced outcome. Nevertheless his breakdown is indicative of Upper Guinean lineage all the way.

- Former “Northern Africa” scores for especially Fula and Cape Verdeans are also returning but still to a lesser degree than in the original 2013-2018 version.

- “Mali” is now peaking among two Sierra Leonean results. Both belonging to Mende persons who very convincingly scored around 100% “Mali”. While for actual Malians the outcomes were more variable. Obviously more samples would be needed to consolidate this finding. But it seems apparent already that Ancestry has been rearranging their set up so that “Mali” now also includes not only Sierra Leone but also Liberia and Ivory Coast in fact (see this map).

- This is not a completely satisfactory solution (see also below). However for Sierra Leoneans themselves I suppose this would count as an improvement as formerly they were not explicitly included in any region. And their DNA results therefore were split in between “Ivory Coast/Ghana”, “Senegal” and “Mali” in the 2013-2018 version. With proper interpretation I did still find this previous set-up to be informational too. Especially when wanting too detect a finer substructure for Atlantic speakers in Sierra Leone (see this page).

- The “Mali” region is still quite predictive for actual Malians. But no longer to the exaggerated degree as in the 2018 version. Which is probably more realistic and in in line with Mali’s greater ethnic diversity which cannot be covered by just one single region. As demonstrated by one Soninke result with a recovered primary “Senegal” score of 61%, the “Mali” region is NOT per se an exclusive indication of Mande lineage. Due to the inclusion of Sierra Leone and Liberia as well as overlap into (Gur speaking) Burkina Faso and even northern Nigeria other ethnic options still remain possible as well. Many people tend to underestimate the diversity and differentiation among Mandé speakers. Which is more so a loose grouping based on linguistic aspects rather than any unified ethnic identity let alone fully shared genetics. See also maps on this page.

West Africans (Lower Guinea)

Figure 1.2 (click to enlarge)

“Nigeria” has become very predictive of southern Nigerian DNA in general. But probably more so for Igbo’s. “Ghana”‘s predictive accuracy has crashed however especially for people of Akan and also Liberian descent. Formerly covered to an impressive extent by the “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region, which has now been canceled.

***

Table 1.2 (click to enlarge)

***

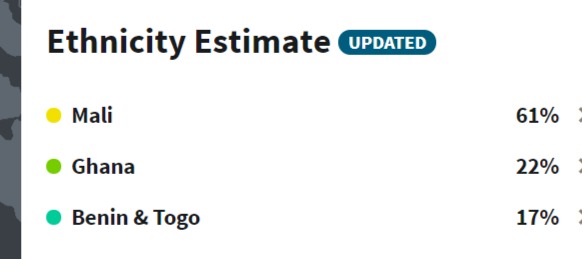

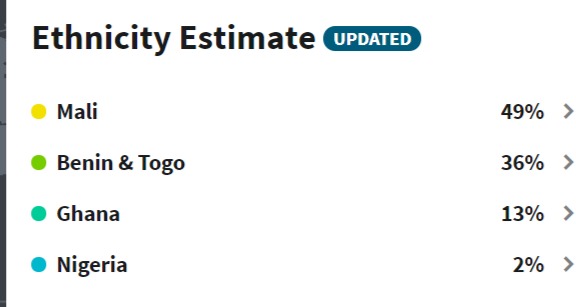

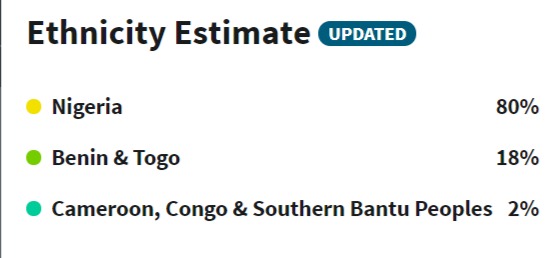

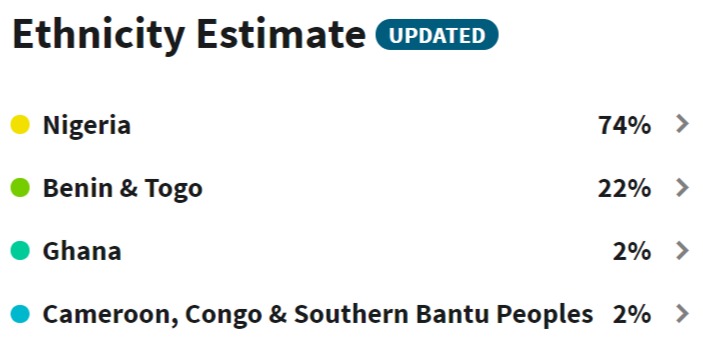

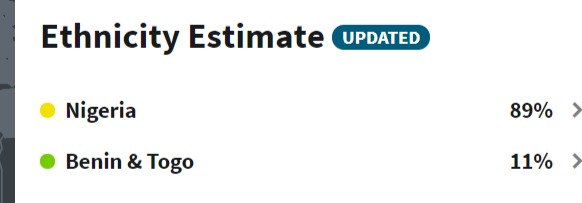

- To start with the good news the predictive accuracy for “Nigeria” has never been better on Ancestry! At least for southern Nigerians themselves. Due to Ancestry’s over-smoothing algorithm it might work out differently for Afro-Diasporans though (see section 3). Still the group averages for both my Igbo and Yoruba survey participants look very convincing. A much sharper delineation now exists with neighbouring “Benin/Togo” and even more so with “Cameroon, Congo & Southern Bantu”.

- For Hausa-Fulani Nigerians the 2019 update has been somewhat mixed. Although their “Senegal” scores (inherited from their Fula side) have been more than restored. Still their “Nigeria” scores (indicative of their Hausa side) are at a subdued level. At least when compared with the 2013-2018 version. Most of the inflated 2018 “Mali” scores have remained. Hard to say what this is exactly pinpointing (if at all). But I suspect it is more so a mislabeled genetic component which is also found among northern Nigerians without any Fula lineage.

- The bad news is that this part of West Africa still contains a major sore spot: “Ghana”. This renamed region is most likely no longer covered by Ancestry’s Ivorian samples. But this change has not resulted in a more cohesive genetic cluster. Continuing the trend after the 2018 update “Ghana’s” predictive accuracy has plummeted for both Ghanaians and Ivorians. This accuracy once used to be quite impressive for especially people of Akan descent but this is no longer the case. Notice how the group average for “Ghana” among 4 of my Akan survey participants doesn’t even reach 50%. While it used to be 90%!

- And in fact also for Liberians the former “Ivory Coast/Ghana” region was quite predictive. When ignoring the country name labeling. It was especially peaking among people of Kru descent according to my 2013-2018 survey (see this blogpost). But due to the inclusion of Liberia into “Mali” they are now mostly described by that latter region. Which might cause some confusion as after all Liberia is NOT completely consisting of Mande speakers (see this map). And either way “Mali” is not a perfect fit as besides a reduced “Ghana” component also (nonsensical) “Benin/Togo”‘ amounts are now needed to describe Liberian DNA.

- Still not much change in the average “Benin/Togo” amount for my Ewe samples from Ghana. However the remaining part of their regional composition is now more so tending towards “Nigeria”. Rather than towards “Ghana”, which would intuitively make more sense.

- Like wise for one single Beninese survey participant with Gbe background (Ayizo) whose “Nigeria” amount increased considerably (+34%). While his “Benin/Togo” is no longer as convincing as it used to be (66% vs. 84% in the 2013-2018 version). Although based on a very minimal sample size this is indicative of a somewhat reduced coverage by “Benin/Togo” which I also observed among other peoples results.

- After the 2018 update this part of West Africa stood out as having the weakest defined framework for describing the regional origins of local people. Fortunately this has been improved somewhat with the 2019 update. Especially for Nigerians. However for other nationalities the 2013-2018 version of Ancestry’s African breakdown arguably still provides the best fit for their DNA.

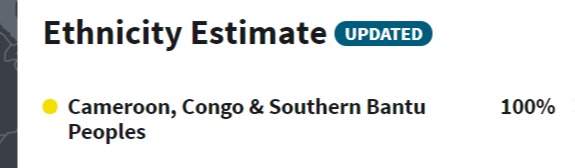

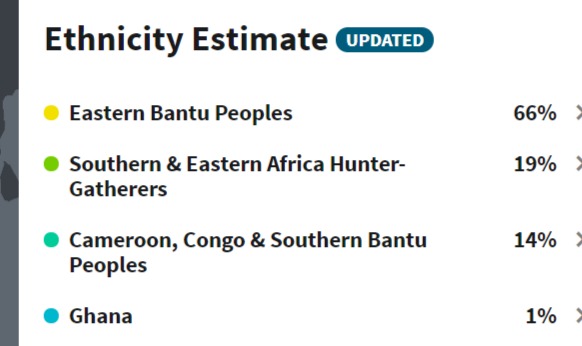

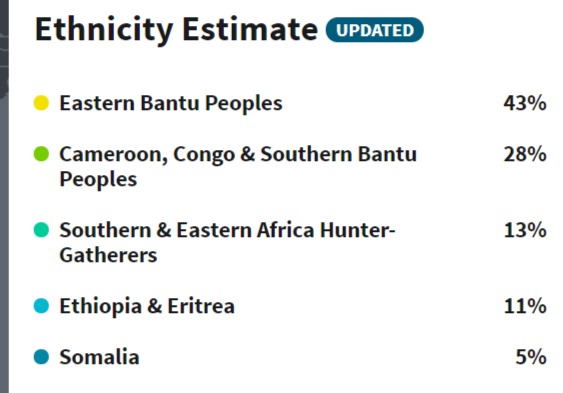

Central & Southern Africans

Figure 1.3 (click to enlarge)

Great deal of genetic homogeneity suggested by these results. Not that surprising given the context of widespread Bantu migrations in this part of Africa. But probably a bit overstated. Do notice also that so-called “Eastern Bantu” is to be found also in Southern Africa!

***

Table 1.3 (click to enlarge)

***

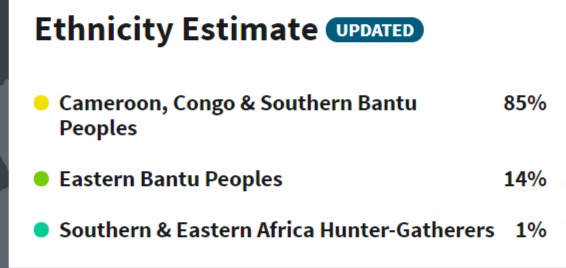

- Hardly any differences between the 2019 & 2019 version for Central and Southern Africans. Therefore I still stand with my comments from 2018 (see this blog post). I already mentioned then that I consider the combined “Cameroon, Congo, and Southern Bantu Peoples” region to be very accurate for Central Africans but not totally comprehensive for Southern Africans.

- Although I still think that the 2013-2018 version had plenty of merit as well I do now somewhat prefer the 2019 version as it enables a sharper delineation with West African DNA. Especially now that “Nigeria” has been boosted in predictive accuracy. Although “Cameroon, Congo, and Southern Bantu Peoples” is of course covering a very wide area. And it is perhaps somewhat bland for especially Central Africans themselves when receiving their results. Even when strictly speaking it is super accurate when Ancestry states that for example an Angolan would be 100% “Cameroon, Congo, and Southern Bantu Peoples”, also taking into account then the Ancestry’s wider regional description and map!

- My main qualm is with the persistence of mislabeled “Eastern Bantu” scores among Southern Africans. Hopefully in the next update Ancestry will be able to once again provide meaningful resolution for Southern Africans. Preferred delineation would be with both Central Africans and Swahili speaking countries from further north.

East & North Africans

Figure 1.4 (click to enlarge)

Some parts of North and East Africa are now well represented in Ancestry’s Reference Panel. Which has lead to straightforward (~100%) estimates for especially Moroccans and Ethiopians. However other countries still remain undersampled which leads to more diverse results. As Ancestry regional framework is still struggling to find a best fit for the complex genetics of this part of Africa.

***

Table 1.4 (click to enlarge)

***

- “Ethiopia & Eritrea” and “Somalia” are the only truly new African regions within this 2019 update. They make for a very useful addition for Northeast Africans themselves. But otherwise hardly relevant for Trans-Atlantic Diasporans. Except perhaps for dispelling misguided notions some people might entertain about having such (historically implausible) lineage. I have not yet seen that many results but the predictive accuracy seems to be on point especially for “Ethiopia & Eritrea”.

- For other Northeast Africans the prediction accuracy of “Eastern Bantu” is still disappointing. This region has been renamed from “Eastern Africa”. But is still barely covering 40% of the regional composition for my Tanzanian, Kenyan, Ugandan and Tutsi survey participants. In some ways more understandable now that also strictly Cushitic regions (“Ethiopia & Eritrea” and “Somalia”) have been introduced. But still not a satisfying outcome. In particular also because this region actually extends into southern Africa.

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” region also has had a minor name change into “Southern & Eastern” instead of “South-Central”. A belated acknowledgement of Ancestry’s usage of Tanzanian Sandawe and/or Hadza reference samples since the 2018 update… (see this blogpost). But I still don’t like this region and I don’t see the added value of it (except for South Africans). I would rather see a new region equipped to single out Nilotic-(like) DNA markers for Northeast Africans. Which is why I prefer the 2013-2018 version for Kenyans, Tanzanians, Ugandans and Tutsi. Also because it provided a more insightful look into their more ancient ethnogenesis (in my opinion). Then again the 2019 update might certainly be said to have been an improvement over the 2018 update.

- For actual Maghrebi the “North Africa” region has become even more predictive. Still peaking with my 2 Moroccan samples but also on the increase for my Algerian survey participants. Regrettably at the expense of the usually minor but still clearly detectable West African admixture being reported for Moroccans and Algerians. Before the 2018 update this ancestral portion was consistently being described in either “Senegal” or “Mali” regional terms. However after the 2018 & 2019 updates it seems to have been incorporated mostly within the “Northern Africa” region. Only leaving room for a very minimal scattering of various West African regions. Historically speaking a mostly Upper Guinean component reflecting West African admixture among Maghrebi’s is much more plausible and therefore more informative.

2) Ancestry’s Reference Panel & Algorithm

Table 2.1 (click to enlarge)

Take note of the huge increase of Nigerian samples (+411) while the number of Ghana samples has actually decreased (-/-15). Most likely due to the canceling of Ivorian samples. Keep in mind that several regions have had name changes when compared with Ancestry’s 2018 version: “Eastern Bantu” used to be “Eastern Africa”; “Southern & Eastern Africa Hunter-Gatherers” used to be “Africa South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” and most importantly “Ghana” used to be “Ivory Coast/Ghana”.

***

For a greater understanding of your Ethnicity Estimates it is always advised to learn more about the methodology used by Ancestry to produce their results. In particular Ancestry’s Reference Panel and their customized algorithm are key aspects. Last year I dealt with this topic in great detail. And much of what I discussed for the 2018 update is still relevant also for this 2019 update.

In particular in regards to Ancestry’s algorithm which apparently has not been changed with this update. Because of the way it has been designed this algorithm still tends to have a homogenizing or over-smoothing effect. The composition and number of African samples contained in Ancestry’s Reference Panel has however changed quite a bit. As can be seen in the overview above. Ancestry’s new white paper is still an insightful, albeit a rather technical account. Recommended reading:

- Ancestry’s 2019 Reference Panel

- Ethnicity Estimate 2019 White Paper (Ancestry)

- Discussion of Ancestry’s 2018 Reference Panel & Algorithm

____________________

“The current AncestryDNA reference panel has 40,017 DNA samples that divide the world into 60 overlapping regions and groups” (Ancestry, White Paper 2019)

” it is not only absolute numbers you should be concerned about but also relative standing.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

“over-sampled regions seem to suck in ethnicity estimate %’s at the expense of under-sampled regions. In a way functioning like a magnet” (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

“For correct interpretation of AncestryDNA’s African regions it is however still crucial to not only know the nationality but also the ethnic backgrounds of the African samples included in Ancestry’s Reference Panel.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018).

____________________

In regards to Ancestry’s updated Reference Panel (see table 2.1) I would just like to make the following points. Otherwise please refer to my 2018 discussion.

- The proportion of African samples in Ancestry’s previous Reference Panel was about 8% (1395/16638) after the 2018 update. However now this relative share of total African samples has decreased to around 5% (2310/40017). A steady decline when compared with the original 2013-2018 version which had a share of African samples of about 15% (464/3000). The overwhelming part of newly added samples (around 17,000) has been used by Ancestry to achieve increased resolution for the new “Indigenous Americas” regions.4

- More than 70% of the increase in African samples went to just two regions: “Nigeria” (+411) and “Mali” (+244). This seems to have been beneficial especially for recovering and even improving on the predictive accuracy of “Nigeria”. But a considerable increase in samples (+83) has also worked out positively for “Senegal”.

- The former sample imbalance within West/Central Africa has been resolved for the most part. However one obvious sore spot is remaining. “Ghana” is the only West African region which saw a decrease in number of samples. (-/-15). Most likely due to the removal of Ivorian samples. Also relatively speaking it looks undersampled when compared with “Mali”, “Benin & Togo” and “Nigeria”. This seems to have seriously undermined the predictive accuracy of “Ghana”.

- As far as I know Ancestry still does not give any information about the background of their African samples beyond nationality. It seems likely that a greater part of the added Nigerian samples may have been southern Nigerians. Possibly also many Yoruba and even more so Igbo customer samples have been used. As from my observation they tend to test with Ancestry in great numbers.

- The increase in samples for “Mali” has also been quite spectacular (+244). Especially when considering that the total number used to be only 16 in the 2013-2018 version! I find it very intriguing how Sierra Leone, Liberia and also Ivory Coast are now explicitly included into this region (according to Ancestry’s own regional description/map). Given the nearly 100% “Mali” scores for two of my Sierra Leonean survey participants (both confirmed Mende) I have a strong suspicion that perhaps also Sierra Leonean samples have been added. Because Mende samples are available from academic databases such as the 1000 Genomes Project which is also utilized by Ancestry.5

- One also wonders what happened with the Ivorian samples which are no longer being used for “Ghana”. Are they now instead being used for “Mali”? This is of course merely speculation on my part. But if true then clearly Ancestry needs to adjust the country name labeling for “Mali”. As well as be much more forthcoming about possible implications of “Mali” scores. It should go without saying that Ancestry’s customers have a right to be properly informed about such important changes!

Predictive accuracy according to Ancestry

Chart 2.1 (click to enlarge)

Source: Ancestry’s White Paper (2019, p.9). Red arrow added by myself. This chart depicts the prediction accuracy for each African region. The average or median being marked by the black line in the middle of each coloured boxplot. Based on how Ancestry’s African samples themselves score for each region. Notice the wide range of estimates. Still most regions have improved in accuracy, especially “Nigeria” and “Senegal”. However “Ghana” clearly has the worst accuracy. Compare with this chart for the 2018 version and this this chart for the 2013-2018 version.

***

The chart above speaks for itself so not much further comment needed. Except that I find that my independently conducted survey makes for a good addition (see table 1). As it covers more countries and also allows for ethnic specificity. Still Ancestry’s info is pretty much in alignment as I also found that the predictive accuracy for “Nigeria” and “Senegal” has been greatly improved. Most other regions have been quite steady. While “Ghana” is currently the weakest link in Ancestry’s African breakdown. Within their White Paper (p.25) Ancestry also points this out by mentioning the weak so-called recall rate for “Ghana”. This was already low after the 2018 update (0.61, see this chart) and is now only 0.54. This measure is defined by Ancestry as follows: “Recall can be thought of as how much of the true ethnicity is called by the process.”. It is calculated based on the results of mixed (within Africa) individuals with known background. Very relevant also for Afro-Diasporans who are almost by default of mixed African origins!

Oversmoothing algorithm?

____________________

“ One important consequence of Ancestry’s new algorithm seems to be the tendency to stick everything in as few as possible big regions rather than having things divided up into a dozen or so small percentages” (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

“good for people with low genetic diversity and good representation of their nationality within Ancestry’s Reference Panel. However for people with more complex background, incl. recently mixed individuals, Ancestry’s new algorithm does not always perform as expected. “ (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

“The implications for Afro-Diasporans could be even more far-reaching as after all almost by default Trans-Atlantic Afro-descendants will have intricately mixed origins from across West, Central and Southeast Africa in mostly unknown regional proportions. […] Therefore the previous algorithm might have been more suitable to deal with this complexity. While the current one might serve to underestimate or simplify the various regional origins of Afro-Diasporans.” (Fonte Felipe, 2018)

____________________

Just as a reminder some quotes from my previous discussion of Ancestry’s algorithm in 2018. In my African survey this circumstance of a homogenizing algorithm is manifested especially when African customers receive results of nearly 100% for any given region. Which can be off-putting because although usually accurate it also can be perceived as lumping people together without taking into account finer distinctions. But to be fair this is also a matter of preference or better yet a trade-off. Would you like to have your ancestral origins described within a relatively recent time frame and directly relating to your family tree within the last few generations? Or rather results which are based on a much wider time frame which focuses on so-called deep-ancestry? From which also ancient migrations and general population histories may be revealed. A solution for the near future might be to offer two versions of ethnicity estimates. Or also combining with Ancestry’s finer-detailed genetic community/migration feature. Which then should naturally be expanded to cover Africa as well!

Either way, as it stands right now Ancestry’s algorithm is quite well-suited in many cases. Usually for people with less complex or well-sampled origins. But it will often be a different story for more mixed people or with origins which are not well represented within Ancestry’s Reference Panel. As Ancestry’s algorithm might then tend to either downplay genetic complexity or misrepresent it. At times resulting in a distorted and potentially misleading overview (without proper interpretation). As much is also conceded by Ancestry itself.6 To be sure I do think this oversmoothing effect has become less eye-catching now that Ancestry has created a more balanced West African Reference Panel. But still this remains especially relevant for Afro-Diasporans as will be discussed in the next section.

____________________

“Overall, we found evidence for a differential origin of the African lineages in present day Afro-Caribbean genomes, with shorter (and thus older) ancestry tracts tracing back to Far West Africa (represented by Mandenka and Brong), and longer tracts (and thus younger) tracing back to Central West Africa.” (Moreno-Estrada et al., 2013, p.11)

____________________

Another interesting way to look at this issue is by revisiting the highly significant research findings of Moreno-Estrada et al. (2013). In their breakthrough study they were able to distinguish various waves of regional African lineage by way of DNA segment size. Due to greater dilution and recombination across the generations the more scattered and therefore smaller DNA segments were associated mostly with Upper Guinean lineage (“Far West Africa”) for their Hispanic Caribbean samples. The longer DNA segments which had remained more intact due to genetic inheritance being more recent were mostly identified as being of Central African origin.

Given that Ancestry’s algorithm is designed to focus especially on longer DNA segments this could have a great impact on Ancestry’s regional estimates for not only Hispanic Caribbeans but also other Afro-Diasporans. The risk being that more recent lineage will be favoured above older lineage in Ancestry’s detection. Or put differently smaller and therefore older DNA segments might get skipped over. When there is no major difference between regional origins for both time frames there will not be any problem (as is the case for Cape Verdeans) however otherwise some distortion might occur. As will be shown in the next section. See also my review of this study in 2015:

- Reconstructing the Population Genetic History of the Caribbean (Moreno-Estrada et al., 2013)

3) African breakdown for AncestryDNA testers across the Afro-Diaspora

Table 3.1 (click to enlarge)

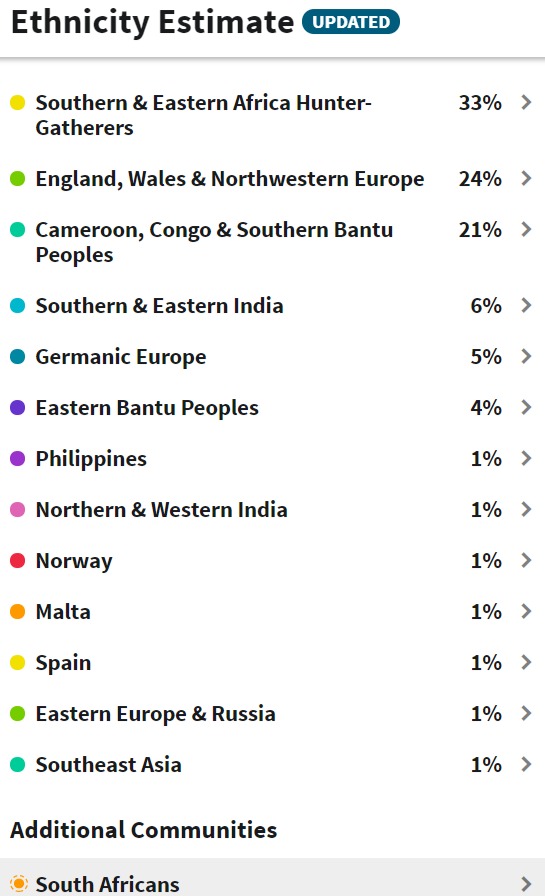

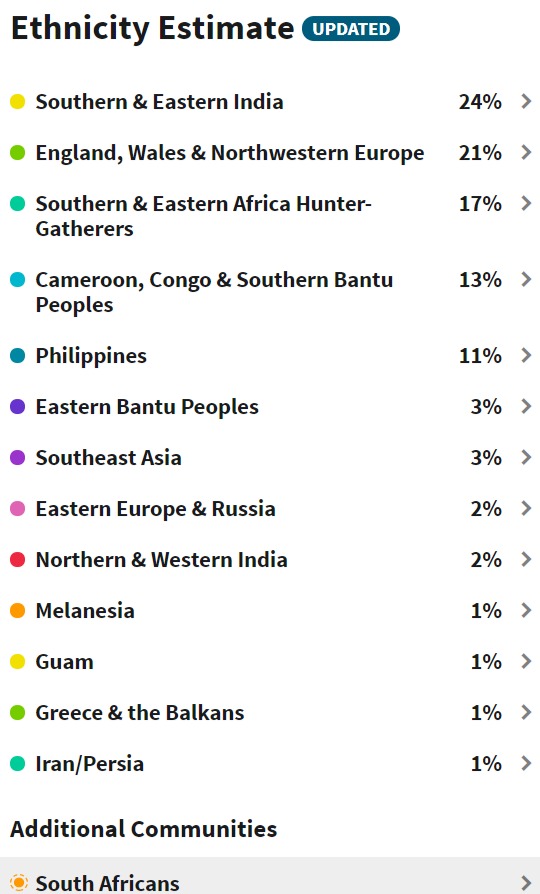

Based on the updated results for 55 AncestryDNA testers from across the Afro-Diaspora. Obviously some major differences when compared with their pre-update results. However not in a completely random manner! The primary regional scores for each nationality still make sense, historically speaking. Even when it is apparent that especially the “Ghana” scores are now very much understated. The individual results can be seen further below. Or also follow this link for my spreadsheet.

***

In order to judge how Ancestry’s 2019 update has impacted the results of people across the Afro-Diaspora I have also performed a small but still comprehensive survey for various Afro-descended nationalities (n=55). As already argued above it might very well be that Ancestry’s update may be more beneficial for some people than for others. All depending on your background. For example the homogenizing effect of Ancestry’s algorithm appears to be most well-suited for in particular Cape Verdeans. While the newly defined “Mali” region and reinforced “Nigeria” region look quite adept for African Americans especially. But the seriously weakened “Ghana” region obviously has a negative effect in particular for Jamaicans and Barbadians. In my discussion below I will be contrasting with historical plausibility as always. Furthermore it will also be useful to look into my previous assessment of the African breakdown of these same nationalities, based on the 2013-2018 version and with a much greater sample size (n=1264):

- Online spreadsheet containing all individual results (before and after update)

- Documented ethnic/regional origins of the Afro-Diaspora (seek out sub-pages relevant to your background)

- Afro-Diasporan AncestryDNA Survey (2013-2018 version)

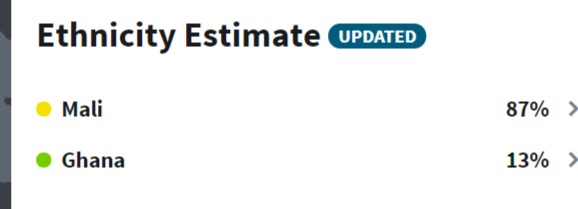

The main flaw of the 2018 update was the consistent appearance of heavily inflated “Benin/Togo” and “Cameroon, Congo, & Southern Bantu” scores. Resulting in a dramatic decrease of “Nigeria” amounts. Especially for African Americans and West Indians completely unwarranted and in contradiction with their known African regional roots. Furthermore also “Mali” scores were usually overpowering “Senegal” scores. This was especially an issue for Cape Verdeans and Hispanic Americans. The current 2019 update has brought back “Nigeria” but with a heavy kick! Seemingly an over-correction seems to have taken place. Mostly at the expense of a steep decline in “Ghana” scores. In addition “Senegal” scores have been restored whenever they were formerly (2013-2018 version) appearing as a primary or otherwise substantial region. As much can already be seen from the overview above.

As was already the case during the 2018 update it is still only 6 African regions which really matter for Trans-Atlantic Afro-Diasporans. Even when the total number of African regions has now expanded to 11. The 2 newly added regions for Northeast Africa have not been reported at all for any of my 55 survey participants. Not even in trace amounts. Which is of course in accordance with historical plausibility. For “Eastern Bantu” and “Hunter-Gatherers” some minimal amounts of around 1% were at times reported. Which might be indicative of something distinctive with proper corroboration. But still all in all insignificant. As can be seen from the group averages. I have applied a correction for “Northern Africa” as usually these scores will have been inherited by way of Iberian or Canarian ancestors for my Hispanic & Cape Verdean survey participants (even when a Sahelian ancestral scenario still is possible as well).

Reviewing table 3.1 it is apparent that Ancestry’s 2019 update has made a great impact indeed. However not in a completely random manner! Usually big shifts taking place between neighbouring and therefore genetically related regions. To be grouped together in macro-regions, as will be discussed further below. Also from a historical plausibility perspective this overview does not look inconceivable or completely absurd for the most part. The primary regional scores for each nationality still make sense, historically speaking. Even when it is apparent that especially the “Ghana” scores are now very much understated.

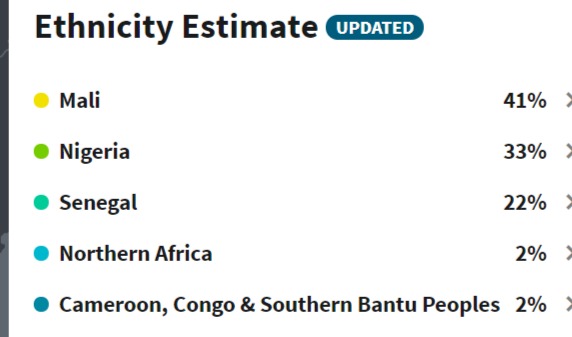

We can still clearly recognize the Upper Guinean founding effect I have blogged about many times already for Hispanic Americans. Especially for Mexicans the level of “Senegal” (45%) is very impressive now. Similar to my Cape Verdean survey participants it is now even higher than it used to be during the 2013-2018 version. It is quite likely that “Senegal” scores are a bit understated for African Americans and West Indians. But ranking wise this outcome should still be as expected. What I find very intriguing is that “Mali” is now peaking among African Americans. And no longer among Cape Verdeans and Hispanic Americans. The difference is not that great but still indicative of a shift towards Sierra Leone and Liberian DNA now also being detected by way of “Mali”. While formerly most of it might have been falling under “Ivory Coast/Ghana”.

Especially when viewing the Jamaican and Barbadian results it becomes very clear how “Ghana” has taken a sharp turn for the worse. For some other nationalities it has simply vanished all together. Definitely not in accordance with historical expectations and also not with their pre-updated results (2013-2018 version)! Still no coincidence that the highest remaining “Ghana” scores should be found among Barbadians. The primary “Nigeria” scores may look a bit exaggerated. But in itself this outcome is not at all surprising as Bight of Biafra lineage (mostly southeast Nigeria) is abundantly documented for both West Indians and also African Americans. And perhaps tellingly also especially predominant during later periods of slave trade, at least for Jamaica and Barbados.

“Benin/Togo” has become a bit subdued, although it is usually not caving in against reinforced “Nigeria”. Highest levels being reached among Barbadians, Jamaicans and Haitians is in line with expectations. The “Cameroon, Congo, & Southern Bantu” region is at it highest for Brazilians, as it should be. When going by recorded slave trade patterns. Also Haitians ending up with a primary score for this region makes historically sense, given their strong Congolese heritage. However a bit more surprising is the slight shift to Central African DNA being detected among Hispanic Caribbeans. Naturally this might be genuine to a major degree. But I have a feeling this trend is also somewhat overstated. Probably due to Ancestry’s algorithm being over-focused on longer DNA segments. This becomes apparent when comparing with their 2013-2018 results which instead showed a primary “Senegal” group average. In particular for Puerto Ricans the difference is quite stark. Compare again with my discussion of Moreno-Estrada et al., 2013 above.

Much more consistency when applying a macro-regional framework

Map 3.1 (click to enlarge)

Combining various levels of regional resolution: on the left the 4 main regions of provenance for Afro-Diasporans (based on slave trade records, see also this link). African ethno-linguistic groups according to the most recent classification are depicted in the middle (see also this link). The map on the right features the 11 African AncestryDNA regions after the 2019 update.

***

One might easily get the impression that each update on Ancestry only leads to more random changes. But do notice from the screenshots below that the macro-regional breakdown has remained pretty much the same. To make more sense of my Afro-Diasporan survey findings across the years I have been using an additional more basic macro-regional framework divided into:

Basically combining interrelated & neighbouring AncestryDNA regions on a macro-level. Such a grouping also being based on historical and ethno-linguistic considerations, aside from genetic ones (see maps directly above). Only meant to be indicative of course and to be used as proxies! Naturally due to genetic similarities and other sources of blurriness there might also still be overlap between macro-regions. However because the 2019 update has brought about a much sharper delineation between “Nigeria” and “Cameroon, Congo, & Southern Bantu” this has now actually improved for West Africa versus Central/Southeast Africa. Only “Mali” is now still somewhat crossing over into Lower Guinea. But still I find it reassuring that drastic proportional changes between macro-regions turn out to be much less common than any relative shifting between neighbouring regions within either Upper- or Lower Guinea or Central & Southeast Africa.

In fact most of the major changes shown below appear to represent internal reshuffling within any of the three major macro-regions. For example the shift of primary “Mali” scores into “Senegal” for Mexicans. Or primary “Ghana” scores into “Nigeria” for Jamaicans. Suggesting that Ancestry might not be able yet to finetune between neighbouring and genetically closely related regions. However in the greater scheme of things this less specific macro-regional framework does usually do justice to what we know about the main African roots for my survey groups.

Because Ancestry’s 2018 update was basically a downgrade and a temporary lapse I am only considering the 2013-2018 and the updated 2019 versions in my comparisons below. I have also kept score of the frequency of top ranking regions within the African breakdown (see numbers appearing in the blue bar below the regional group averages). The individual screenshots are being shown side by side for the same person. The 2013-2018 version on the left and the updated 2019 version on the right.

African Americans

Table 3.2 (click to enlarge)

Hardly any changes from a macro-regional perspective. The shift from “Benin/Togo” into “Nigeria” is very likely to have been an improvement. Take note that combined Central African lineage is being maintained at exactly the same level. While within the Upper Guinean section “Mali” is showing up much more strongly now. Aside from genuine Malian/Guinean lineage of course also Sierra Leone and Liberia connections being very likely for African Americans. In particular those with South Carolina roots!

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Jamaicans

Table 3.3 (click to enlarge)

Going by my macro-regional format no major changes. Notice how the share of Lower Guinea has remained exactly the same! However a drastic decrease in former “Ivory Coast/Ghana” scores seems to be compensating for the restored “Nigeria” amounts. Apparently an over-correction taking place. See this table to view the impact of the 2018 update incorporated as well. Or also this blog post for a more detailed discussion: 100 Jamaican AncestryDNA results.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Barbadians

Table 3.4 (click to enlarge)

Similar to my Jamaican survey group again a HUGE drop in “Ghana” scores. Interestingly “Benin/Togo” has remained practically the same. While “Nigeria” seems to have increased also partially at the expense of “Cameroon,Congo and Southern Bantu”. Therefore a somewhat greater shift also macro-regionally speaking. Possibly Ancestry’s reinforced “Nigeria” region is now better able to pick up on Bight of Biafra lineage which was formerly described as “Cameroon/Congo”. The lower degree of Central African lineage being indicated does seem to correspond better with documented slave trade for Barbados.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Brazilians

Table 3.5 (click to enlarge)

Quite a sharp increase of the Central & Southeast African component. Historically speaking still plausible. Also in comparison with other parts of the Afro-Diaspora. But possibly somewhat exaggerated due to Ancestry’s algorithm. Take note that one of my Brazilian survey participants (BR04) used to have “Senegal” as top region in the 2013-2018 version. But with the 2019 update this changed into “Cameroon,Congo and Southern Bantu”.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Haitians

Table 3.6 (click to enlarge)

Again only minimal changes in the 3-way macro-regional breakdown. But otherwise still a noticeable increase of “Nigeria”. Mostly at the expense of “Benin/Togo” and “Ghana” it seems. The Central African component actually also increasing. Just speculating, but possibly also reflecting how Congolese lineage among Haitians tends to be of a more recent date than Beninese lineage (see this blog post). And due to its design Ancestry’s algorithm might possibly underestimate Beninese DNA therefore.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Cape Verdeans

Table 3.7 (click to enlarge)

A practically 100% Upper Guinean score is now being obtained for Cape Verdeans! Which would be in line with historical expectations (see this website). And therefore certainly may count as an improvement. Even when unexpected regional scores from outside Upper Guinea might still have been indicative of something distinctive in individual cases (to be corroborated by DNA matches). Although as I have always suspected for the greater part these scores were just misreadings by Ancestry. See also 100 Cape Verdean AncestryDNA results.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Mexicans

Table 3.8 (click to enlarge)

Once more a pretty consistent breakdown when taking into account only the three major macro-regions. Mexico’s significant Central African heritage is still clearly showing up. In the 2013-2018 version my Mexican survey group used to have the highest “Mali” group average (also with greater sample size!). Which was quite remarkable. From the 2019 update these “Mali” scores have now mostly been translated into “Senegal”. Which frankly would be much more in line with predominantly coastal Upper Guinean origins (similar to Cape Verde). I also included one result (MX05) from the Costa Chica with increased total African admixture! His breakdown is still pretty much the same as those for Mexicans with smaller amounts of African admixture.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Dominicans

Table 3.9 (click to enlarge)

Also for Dominicans no drastic changes in their macro-regional framework. Which in my previous research I have identified as being one of the most balanced and evenly mixed among the Afro-Diaspora (along with Puerto Ricans). Reflective of the very diverse slave trade history of the Hispanic Caribbean in general. However I do find it noteworthy that their Central African component is increasing slightly. Only at the expense of Lower Guinea though. Interestingly even “Nigeria” is decreasing somewhat.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

Puerto Ricans

Table 3.10 (click to enlarge)

Surprising increase in the Central African share. Not only macro-regionally but also when measured by primary regional scores (as shown in the blue bar; for the 2013-2018 version there were also 2 primary “Africa North” scores). Although not overtly drastic and still more or less in line with historical expectations for Puerto Ricans. The 3-way breakdown is still very balanced out. Similar to what I have observed for Dominicans. In light of my previous discussion of the Moreno-Estrada et al. (2013) findings I do strongly suspect that Ancestry’s algorithm has something to do with this outcome.

***

Individual screenshots (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge)

***

4) Getting back on track again

Map 4.1 (click to enlarge)

The map is showing all eleven new African regions available after Ancestry’s 2019 update. As always close scrutiny is required to evaluate the usefulness of this new African breakdown. It looks like the damage done by the horrendous 2018 update has been mostly repaired (except for the derailing of “Ghana”). And depending on your background this new African breakdown might even be an improvement over the original 2013-2018 version! Still Ancestry needs to step up its game and make sure all passengers are on board. Especially the ones with roots in the wider Ghana area 😉 Photo credits for top picture.

***

____________________

“Please note that genetic ethnicity estimates are based on individuals living in this region today. While a prediction of genetic ethnicity from this region suggests a connection to the groups occupying this location, it is not conclusive evidence of membership to any particular tribe or ethnic group.” (source: Ancestry)

____________________

Update fatique might very well be the state of mind for a lot of people after this 2019 update on Ancestry. Within two years time they have now received their third version of an approximate sketch of how their African regional roots might be described. Due to wild fluctuations the credibility of their results will be questioned by many… But despite unrealistic expectations Ancestry’s Ethnicity Estimates have never been intended to provide people with a “Alex Haley moment”. Let alone give them a conclusive report on their African lineage!7

I still firmly believe that with correct interpretation these regional estimates can be very useful as a stepping stone for follow-up research (incl. African DNA matches!). And just to get a general idea of where most of your African ancestors hailed from. All according to the latest state of knowledge. Which naturally may be improved upon across time. I find it important to stay positive and focus on what ever informational value you can obtain despite imperfections. Instead of taking an overtly dismissive stance. You do need to make an effort yourself and stay engaged to gain more insight though!

As always it is essential to be fully informed about both strengths and weaknesses for each separate aspect of DNA testing. In this blog post I have performed a before & after analysis among both African and Afro-descended AncestryDNA testers to make a fair assessment of how this 2019 update compares with previous versions. In my review of the arguably failed 2018 update I stated that it was “almost like Ancestry turned back the clock on its African breakdown with practically ten years!“.

I am relieved to say that based on my African survey findings it seems that most of the features of Ancestry’s pioneering African breakdown from the 2013-2018 version have now been resurrected or even improved upon! Much of the focus lost during the 2018 update now seems to have been regained! Then again no major breakthrough has been achieved. Despite the addition of two new regions in Northeast Africa the number of useful regions for Trans Atlantic Afro-descendants has remained the same (6). And also in other aspects Ancestry’s African breakdown is definitely not yet on a high-speed rail track 😉

In fact depending on your background this 2019 update may not always be beneficial. Especially given the seriously derailed “Ghana” region and also due to Ancestry’s over-smoothing algorithm. For many people it may still be the 2013-2018 version which will offer the best fit for your historically plausible regional roots within Africa. I am not saying Ancestry’s 2013-2018 version was without its own flaws. I have frequently pointed out its many limitations and shortcomings. But this should not be an excuse to bash admixture analysis as my previous AncestryDNA survey findings have demonstrated that potentially this tool can be very useful in unlocking the secrets of main African regional lineage for Afro-Diasporans!

Just as a reminder and also for the sceptics out there below a list of redeeming aspects about this 2019 update:

- The continental breakdown pretty much remained consistent in my survey findings (see columns R-U in my spreadsheet). And in most ways has actually improved due to finer regional resolution for Asia, the Americas and Europe.

- Also the macro-regional breakdown usually remained consistent and is mostly in line with historical expectations (see discussion in section 3).

- All of my Afro-Diasporan survey groups can now be identified independently by their assignment to an often very specific genetic community or “migration” (see screenshots in section 3). Very impressive achievement. And one hopes this feature will also be introduced for Africa in the next update!

- Although it does not seem to have been a top-priority during this particular update it is still recommendable that Ancestry increased the number of African samples in their Reference Panel. And also mostly restored its former coherency. The “Ghana” region remaining a major sore spot though.

- It took Ancestry only one year to mostly restore the adequacy of their African breakdown. Which I suppose is a relatively short amount of time for DNA testing companies. This has effectively shown that the 2018 update was a temporary lapse and indeed a downgrade. Despite some reports to the contrary ( 😉 ) Ancestry’s African breakdown is still alive. Most of the groundwork from the 2013-2018 version is available again to build upon towards an even more sophisticated regional framework intended to assist in our ongoing journey to Trace African Roots!

Suggestions for improvement

____________________

- Maintain current coherency of African breakdown and improve by creating less overlapping and more predictive regions

- Add more historically relevant African samples to Ancestry’s Reference Panel. In particular from Angola, Burkina Faso, Guinea Bissau/Conakry, Liberia, Madagascar, Mozambique and Sierra Leone.

- Create new regions and/or migrations centered around these historically relevant samples.

- Bring back the continental breakdown display (subtotals specified for each continent).

- Create new African “migrations”, a.k.a. genetic communities. In particular for Nigeria and Ghana, as sufficient customer samples may already exist.

- Mention the “aggregate ethnicity estimates” for each migration/genetic community.

- Show ethnicity/admixture of shared DNA segments with your matches.

- Avoid misleading labeling of ancestral regions. Providing a false sense of accuracy.

- Enable DNA matching with all the African samples contained in Ancestry’s Reference Panel.

- Encourage African customers to fill in their family tree details or at least provide places of birth in Africa. This would help tremendously for Afro-Diasporans wanting to connect with their African DNA matches

- Insightful “genetic diversity” tabs should be brought back to optimize Ancestry’s transparency towards its customers

- Knowledgeable scholars of African & Afro-Diasporan history should be involved in a re-writing of the regional descriptions.

____________________

This overview above is taken from my previous blog post from June 2018:

Unfortunately hardly any of these suggestions were taken up by Ancestry when they did their update in September 2018. Least of all my principal suggestion to maintain coherency… This new 2019 update has made some real efforts to correct the damage done last year. Especially the addition of African samples for most of the existing regions has been beneficial. The “Ghana” region being a regrettable exception. But Ancestry has still not yet really started to move beyond what was already achieved during the 2013-2018 version. So I might as well give it another shot 😉 I still stand by my statements quoted above. If you are not happy with your updated results let Ancestry know about it!!! Also forward them this link (when in agreement of course).

In addition I also think Ancestry needs to reconsider the usefulness of its customized algorithm for people with greatly mixed or undersampled origins. Or perhaps come up with two versions of their Ethnicity Estimates, (according to implied timeframe) as also seems to be suggested in their White Paper. Or otherwise start integrating African “migrations”, based on DNA matching strength. This could really revolutionize their product and bring it to the next level!

I find it worrisome that the general level of transparency is yet again decreasing with this update on Ancestry. To be sure there are still plenty of helpful sections/pages offering guidance and context (see this one for the 2019 update in particular). But compared with the 2013-2018 version it is clearly getting worse. See also my comments in section 2 about the need to know the ethnic background of the African samples contained in Ancestry’s Reference Panel. Also the regional descriptions have now become very minimal and bland. Even containing obvious and sloppy mistakes at times…8

Then again Ancestry’s customers do also have their own responsibility in this and should not just expect quick and easy answers. In order to avoid being left confused or mislead by your new results of course you will need to make some effort to inform yourself properly. Also after this 2019 update the motto remains: pay close attention to the regional maps integrated within your Ethnicity Estimate! Don’t get obsessed over the country name labeling.9 That will only be a waste of time. Get over it and move on! Realize the labeling is merely intended as an approximate proxy. Which can still be helpful if you also take into account neighbouring countries, macro-regions, the known migrations of ethnic groups, pre-colonial history etc., etc.. Consider it as an opportunity to get better acquainted with Africa! See also:

My last advise would be to hang in there! This update may not yet live up to all of your expectations. Even when for many people it will be beneficial (depending on background). Further improvement may still be forthcoming, if not on Ancestry than elsewhere! In the meanwhile keep aiming for maximizing the ancestral clues you may derive from whichever informational source available to you. Be it your admixture results, African DNA Matches, genetic genealogy, relevant historical context etc.. Judge each case on its own merits. Combine insights from different fields to achieve complementarity!

5) Screenshots of African updated results

I will only be posting a limited selection of screenshots. But this array does cover all main parts of Africa. Obviously there might be greater individual variation within each country or even within a particular ethnic group. Still this should already be quite illustrative of the main patterns I have described above. As far as I was able to verify all of the following screenshots below are from persons with four grandparents from said nationality/ethnicity, unless specified otherwise. But naturally I did not have absolute certainty in all cases. Practically all results have been shared with me by the DNA testers themselves. I like to thank all my survey participants for having tested on AncestryDNA and sharing their results online so that it may benefit other people as well!

GAMBIA

***

***

SENEGAL (Wolof, Fula, Serer)

***

***

SENEGAL (Wolof)

***

***

FULA? (?)

***

***

SENEGAL (Fula)

***

***

SENEGAL (Fula)

***

SENEGAL & GAMBIA (Fula)

***

***

FULA? (?)

***

***

SENEGAL & GUINEA (Fula)

***

GUINEA (Fula)

***

***

GUINÉ BISSAU (Fulacunda)

***

***

MALI (Soninke)

***

***

MALI (Bambara & 1/4 Moroccan)

***

***

MALI & MOROCCO

***

***

SIERRA LEONE (Mende)

***

***

SIERRA LEONE (Mende)

***

***

LIBERIA (Grebo & Vai)

***

***

LIBERIA (Bassa & Americo-Liberian)

***

***

LIBERIA (Vai, Bassa, Gbandi & Americo-Liberian)

***

***

LIBERIA (Kru/Kpelle)

***

***

LIBERIA (Northern?)

***

***

LIBERIA (Kru)

***

***

LIBERIA (?)

***

***

LIBERIA (?)

***

***

LIBERIA (?)

***

***

LIBERIA (Grebo & Lofa county)

***

***

IVORY COAST (3/4 Akan & 1/4 Krio (Sierra Leone))

***

IVORY COAST (7/8 Akan & 1/8 Krio (Sierra Leone))

***

***

GHANA (Akan)

***

***

GHANA (Akan)

***

***

GHANA (Akan:Ashanti & Sefwe)

***

***

GHANA (Akan & Ga)

***

***

GHANA (?)

***

***

GHANA (Akuapem & Ewe)

***

***

GHANA (Northern)

***

***

GHANA (Ewe)

***

***

GHANA (Ewe)

***

***

GHANA (Ewe)

***

***

NIGERIA (Igbo)

***

NIGERIA (Igbo)

***

***

NIGERIA (Igbo)

***

***

NIGERIA (Igbo)

***

NIGERIA (Igbo)

***

***

NIGERIA (Igbo & Yoruba)

***

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba)

***

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba)

***

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba)

***

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba)

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba)

***

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba)

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba, perhaps distant Aguda/Afro-Brazilian?)

***

***

NIGERIA (Edo?)

***

***

NIGERIA (Igbo, Edo & Yoruba)

***

***

NIGERIA (Yoruba & Edo?)

***

***

NIGERIA (Bini, Itsekiri, Urhobo & Isoko)

***

***

NIGERIA (& 1/4 Liberia?)

***

***

NIGERIA (Hausa-Fulani)

***

***

NIGERIA (Hausa-Fulani)

***

***

CAMEROON (Oroko/Balundu)

***

***

CAMEROON (Bulu)

***

EQUATORIAL GUINEA (Fang)

***

GABON (Fang & Bateke)

***

CONGO BRAZZAVILLE (Bakongo)

***

CONGO (DRC) (?)

***

***

CONGO (DRC) (?)

***

***

ANGOLA (Bakongo)

***

ANGOLA (?)

***

ANGOLA (?)

***

***

ZAMBIA (?)

***

ZAMBIA (?)

***

ZIMBABWE (Shona?)

***

ZIMBABWE (Shona?)

***

ZIMBABWE (Shona?)

***

ZIMBABWE & SOUTH AFRICA

***

ZIMBABWE (Shona?)

***

***

MALAWI (1/2 Chewa & 1/2 Yao)

***

MALAWI (Neno & Lusangazi)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Swazi?)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Swazi?)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Xhosa)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Coloured)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Coloured)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Coloured)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Coloured)

***

***

SOUTH AFRICA (Coloured)

***

***

MADAGASCAR (Northeast)

***

MADAGASCAR (Southwest)

***

MADAGASCAR (Merina?)

***

***

COMOROS

***

RUANDA (Tutsi)

***

BURUNDI (Tutsi)

***

***

TANZANIA (western (Ha, Hangaza))

***

TANZANIA (?)

***

TANZANIA (Jita & Kuria)

***

TANZANIA (Kuria)

***

UGANDA (northern)

***

***

UGANDA (?)

***

UGANDA (Nilo-Saharan: Aringa & Kakwa)

***

KENYA (Kikuyu)

***

***

KENYA (Kikuyu)

***

***

KENYA (Kikuyu)

***

KENYA (1/2 Taita, 1/4 Kikiyu, 1/4 Kisii)

***

***

KENYA (Taita)

***

KENYA (?)

***

KENYA (?)

***

KENYA (?)

***

KENYA (Swahili)

***

ETHIOPIA

***

***

ETHIOPIAN & AFRICAN AMERICAN

***

***

SOMALIA

***

***

TUNISIA (southern)

***

***

ALGERIA

***

***

ALGERIA

***

***

MOROCCO (Casablanca)

***

MOROCCO

***

***

6) Poll: Has this update been an improvement?

Please have a vote and feel free to leave a comment explaining your vote! Just meant to get a general idea 🙂 You might want to compare either with the 2018 update or also take into account the original 2013-2018 version. Of course there are many ways to evaluate if this update has been an improvement or not. Based on your prior expectations, historical plausibility, actual knowledge about your African lineage, Ancestry’s methodology, DNA results obtained elsewhere, overall feeling of Ancestry’s credibility etc., etc.

Please vote according to your background. So for African Americans, West Indians, Hispanic Americans, Brazilians and other parts of the Afro-Diaspora please vote either Yes or No when it says “only to be answered by Afro-descendants”. For Africans or people of partial African background who have complete knowledge about their African lineage please vote either Yes or No when it says “only to be answered by Africans “. This way it will make it easier to see for which groups this 2019 update has been beneficial and which groups have missed the train so to speak ;-).

___________________________________________________________________________

Notes

1) According to some people only continental admixture is to be taken seriously in DNA testing. Sub-continental admixture, a.k.a. ethnicity estimates, a.k.a. regional admixture only being fit for entertainment purposes. I myself have never taken this stance. Preferring to judge each case on its own merits. Attempting to maximize informational value despite imperfections and avoiding source snobbery. Which is why I have conducted my AncestryDNA surveys among Africans and Afro-descendants in the past. Applying an additional macro-regional framework for extra insight (Upper Guinea, Lower Guinea, Central/Southeast Africa).

Basically combining interrelated & neighbouring genetic regions in order to allow certain regional patterns to show up more clearly. This turned out to be particularly helpful when wanting to explore any rough correlation between aggregated AncestryDNA results for Afro-Diasporans and slave trade patterns. Which I indeed established for the most part. See this post below for a summary of how my Afro-Diasporan findings (2013-2018) more or less fall in line with historical plausibility.

Obviously AncestryDNA’s regional breakdown (2013-2018) was rather basic and had several flaws. Still also my African AncestryDNA survey (2013-2018) did produce several potentially insightful findings. Not only for improving the interpretation of the results of Afro-Diasporans. But also for Africans themselves hopefully leading to better understanding of the understudied migration history within the African continent. Both relatively recent (last 500 years or so) and more ancient. I have had many stimulating discussions with Africans who did a DNA test over the years. Unlike what some people might assume many Africans themselves take a great interest in these matters. See also:

2) Practically all African AncestryDNA results have been shared with me by the DNA testers themselves. Naturally I verified the background of each sample to the best of my capabilities but I did not have absolute certainty in all cases. I like to thank all my African survey participants for having tested on AncestryDNA and sharing their results with me so that it may benefit other people as well!

When I first started out in 2013 with my AncestryDNA survey among Afro-descendants I had to wait for a quite while to also include a few African test results. Even when back then I already fully realized their corroborating potential. In the last two years or so DNA testing has fortunately become increasingly popular among Africans. And therefore I was able to compile the data based on 136 African testresults in this spreadsheet. Of which 121 results were used in table 1. Actually I have collected many more African AncestryDNA results over the years. See also these recent blog posts with my final survey findings, based on Ancestry’s 2013-2018 version:

- Fula, Wolof or Temne? Upper Guinean AncestryDNA results 2013-2018

- Akan or Ewe? West African AncestryDNA results 2013-2018

- Igbo, Yoruba or Hausa-Fulani? Nigerian AncestryDNA results 2013-2018

- Final summary: Central & Southern African AncestryDNA results 2013-2018

- Final summary: North & East African AncestryDNA results 2013-2018

3) There is actually solid evidence pointing towards genuine Malian lineage for Cape Verdeans (see section 3 of this blog page). However to a much lesser degree than the previous AncestryDNA results (after 2018 update) were suggesting. Certainly not predominating other types of Upper Guinean lineage, hailing from Senegambia, Guiné Bissau, Guinea Conakry and Sierra Leone! This 2019 update has vindicated my statement last year that:

____________________

“these inflated “Mali” scores are mostly an artefact of Ancestry’s new algorithm as well as their new selection of reference samples (it now has 169 samples from Mali versus only 31 from Senegal and ZERO from Guiné Bissau, see this link). Hence why Cape Verdean’s African DNA now gravitates towards “Mali” rather than to “Senegal”.

____________________

I find that the new “Senegambian & Guinean” category on 23andme has a far more fitting labeling for Cape Verde’s Upper Guinean lineage than either “Mali” or “Senegal”. But still in the wider scheme of things I am not too much bothered by this proxy labeling. As either way it is pinpointing Upper Guinean lineage.

4) This huge addition of “Native American” samples (around 17,000, see this link) is of course not relevant for understanding Ancestry’s African breakdown. Still it might be interesting to know that Ancestry apparently selected these samples among their own customer database. And furthermore these customers of various Latin American backgrounds were very much racially mixed and not 100% Native American”, genetically speaking. According to Ancestry’s White Paper (p. 5/6):

____________________

“When creating reference panel regions reflecting geographic regions for the Americas

and Oceania, we wanted to use only the parts of the genome with ancestry from the indigenous populations. We did this by looking at our previous ethnicity assignments and choosing only the segments of DNA (or windows) where both chromosomes had assignment to an ethnicity region corresponding to the indigenous population. So, whereas most of our regions use DNA from the entire genome of each candidate, for regions from admixed populations we only use a fraction of each person’s genomes.The ethnicity regions where we employ this approach are Indigenous Americas-North, Indigenous Americas-Mexico, Indigenous Americas-Yucatan, Indigenous Puerto Rico, Indigenous Haiti & Dominican Republic, Indigenous Cuba, Indigenous Americas–Central, Indigenous Americas-Andean, Indigenous Americas–Colombia & Venezuela, Indigenous Americas-Southeast, Samoa, Tonga, Polynesia, Melanesia, and Guam.”

____________________

5) Again I can merely speculate about this possible inclusion of Mende samples from Sierra Leone into Ancestry’s Reference Panel. Probably obtained from the 1000 Genomes Project, which is one of the main sources for Ancestry’s Reference Panel (besides the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) database, Ancestry’s own Sorenson/SMGF database and most of all its customer database). This 1000 Genomes Project database contains 128 Mende samples (see this link). These samples (MSL) have most likely also been used by 23andme as well as by various third party ethnicity calculators on Gedmatch and DNA Land.

6) Ancestry does not appear to want to explicitly implicate their custom-made algorithm, only mentioning their Reference Panel. But Ancestry does acknowledge the wild swings within the African breakdown as follows on their Ethnicity FAQ page:

____________________

“Africa presents special challenges.

People from Africa are the most genetically diverse on earth. This makes Africa a tricky place for ethnicity estimation because you need lots of DNA samples to account for all that diversity. With updates to our reference panel, our ability to identify our Nigeria ethnicity region has gotten much, much better. This means that some people might see increases or decreases in their percentage for Nigeria. That also means that the part of your estimate that might now be assigned to Nigeria used to be assigned somewhere else, probably to a nearby region, which mean changes there, too.”

“What’s happening in West Africa?

We know some of our customers with ethnicity regions in West Africa have seen some back and forth in their results from these ethnicity updates. Here are a couple of reasons why and where you might see them in the future.

With updates to our reference panel, our ability to identify our Nigeria ethnicity region has gotten much, much better. This means that some people might see increases or decreases in their percentage for Nigeria. That also means that the part of your estimate that might now be assigned to Nigeria used to be assigned somewhere else, probably to a nearby region, which mean changes there, too.

Benin & Togo and our Ghana region (which used to be Ivory Coast & Ghana) also saw big changes as well. We’ll keep working on all our regions in Africa, but as we improve our ability to identify regions, this can affect your percentages in regions around it.”

____________________

7) Understandably many people desire to have the most specific degree of resolution when searching for their African roots. They want to be able to pinpoint their exact ethnic origins and preferably also know the exact location of their ancestral village. In a way following in the footsteps of the still very influential ROOTS author Alex Haley. Unfortunately these are rather unrealistic expectations to have in regards to DNA testing (at least in regards to admixture analysis.). Not only given current scientific possibilities. But also because such expectations rest on widely spread misconceptions about ethnicity, genetics, genealogy as well as Afro-Diasporan history.

Too often people ignore how the melting pot concept is really nothing new but has always existed! Also in Africa where inter-ethnic mixing has usually been frequent! Throughout (pre) history and maybe even more so in the last 50 years or so. Generally speaking ethnicity is a fluid concept which is constantly being redefined across time and place.

Too often people fail to take into consideration how due to genetic recombination our DNA will never be a perfect reflection of our family tree but might actually also at times suggest very ancient migrations.

- Everyone Has Two Family Trees – A Genealogical Tree and a Genetic Tree (Genetic Genealogist, 2009)

Too often people underestimate the actual number of relocated African-born ancestors they might have (dozens or even hundreds!). As well as the inevitable ethnic blending which must have taken place across the generations.

Too often people are still not informing themselves properly about Africa itself and the documented origins of the Afro-Diaspora. Many specific details may have been lost forever but there is a wealth of solid and unbiased sources available which can help you see both the greater picture as well as zoom in more closely to your own relevant context. See also:

- Fictional Family Tree incl. African Born Ancestors (Tracing African Roots)

- DNA studies for Africans and Afro-Diasporans (Tracing African Roots)

- Documented ethnic/regional origins of the Afro-Diaspora (Tracing African Roots)

- Maps (ethnolinguistic, slave trade, various parts of Africa) (Tracing African Roots)

8) Just to list a few examples (not meant to be exhaustive):

- Regional description for “Senegal” also includes Chad for some strange reason (except when based on Chadian Fula people?). See also this screenshot:

***

***

- The map for “Cameroon, Congo & Southern Bantu Peoples” also shows Guinea???

***

***

- The “Southern & Eastern Africa Hunter-Gatherers” is most likely based on Khoi-San and Tanzanian Hunter-Gatherer samples. At least this would reasonably be the expectation given the labeling and the regional map. However in the regional description there is no mention at all of Tanzania and in stead it seems the previous regional description including Central African Pygmy samples is still being maintained…

***

***

9) The country name labeling is still potentially very misleading when taken at face value. Also after this 2019 update. After all so-called “Mali” is now also to be found in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast and even northern Nigeria! “Cameroon, Congo, and Southern Bantu Peoples” is still covering over 20 countries! With such a wide area covered, it really begs the question why this seemingly exact country name labeling is to be maintained…

On the other hand ancestral categories referring to ethnic groups might be just as deceptive or even more so. As many people will again tend to take them too literally. Underestimating not only the sheer number of ethnic groups existing in Africa (thousands!) but also the complexity of interplay between fluid ethnicity, overlapping genetics and shifting political borders. An intermediate solution might be ancestral regions which are referring to either non-political geography or ethno-linguistic groupings. But I fear there will always be some degree of blurriness involved and exact delineation might be impossible to achieve in many cases.

However to their credit Ancestry is not entirely trying to cover up this tricky issue. From Ancestry’s FAQ section it can be learnt how their regional maps are to be interpreted. They are again not to be taken too literally as Ancestry obviously does not possess perfect information about the genetic background of all Africans! And this should also not be expected from them. But these maps can still be very useful to give you an approximate idea of how widely extended each region might be. As long as you keep in mind these maps are made on a best-effort basis. From my previous survey findings I found that Ancestry tended to underestimate how widespread some of their regions could be. For example “Ivory Coast/Ghana” extending into Liberia and Sierra Leone. They have mostly corrected this in their present update however there may still be some omissions.

____________________

“A region map shows where we find the greatest concentrations of people assigned to a particular region. The maps are made using people born in the area, and where possible we use people with known deep roots in that area. The darker the color, the more people we find who have this region in their estimate. The maps are approximate, and people outside the highlighted shape may still have that region in their estimate. Similarly, not everyone living within the highlighted area will have the region in their ethnicity estimate.” (Source: Ancestry)

____________________