Links to Articles

- Mitochondrial portrait of the Cabo Verde archipelago: the Senegambian outpost of Atlantic slave trade (Brehm et al., 2002)

- Mitochondrial DNA genetic diversity among four ethnic groups in Sierra Leone. (Jackson et al., 2005)

- Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Mauritania and Mali and their Genetic Relationship to Other Western Africa Populations (Gonzales et al., 2006)

- Human Y chromosome haplogroup R-V88 – a paternal genetic record of early mid Holocene trans-Saharan connections and the spread of Chadic languages (Cruciani et al. 2010)

Links to Blog Posts

Charts, graphs, tables, maps etc.

***(click to enlarge)

Mitochondrial portrait of the Cabo Verde archipelago: the Senegambian outpost of Atlantic slave trade (Brehm et al., 2002)

***(click to enlarge)

Mau=Mauritania; Sen=Senegal; GuB=Guinea Bissau; Mal=Mali; SiL=Sierra Leone; NiN=Niger-Nigeria; Cam= Cameroon. Source: Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Mauritania and Mali and their Genetic Relationship to Other Western Africa Populations (Gonzales et al., 2006)

***(click to enlarge)

AtN= Atlantic Northern; Atl=Atlantic; Man=Mande; VoC=Volta-Congo; AfA=Afro-Asiatic. See this page for ethno-linguistic maps. Source: Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Mauritania and Mali and their Genetic Relationship to Other Western Africa Populations (Gonzales et al., 2006)

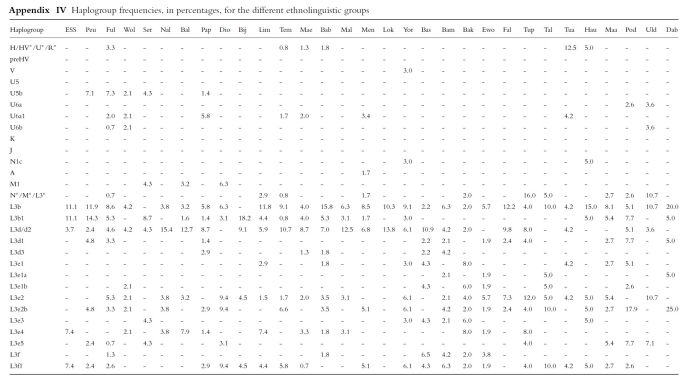

***(click to enlarge)

ESS=Eastern Senegal Speakers; Peu=Peulh; Ful=Fulbe; Wol=Wolof; Nal=Nalu; Bal=Balanta; Pap=Papel; Dio=Diola; Bij=Bijago; Lim=Limba; Tem=Temne; Mae=Mandenka; Bab=Bambara; Mal=Malinke ;Men=Mende; Lok=Loko; Yor=Yoruba; Bas=Bassa; Bam=Bamileke; Bak=Bakaka; Ewo=Ewondo; Fal=Fali; Tup=Tupuri; Tal=Tali; Tua=Tuareg; Hau=Hausa; Maa=Mandara; Pod=Podokwo; Uld=Ouldeme; Dab=Daba. See also this page for Upper Guinean ethnic groups. Source: Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Mauritania and Mali and their Genetic Relationship to Other Western Africa Populations (Gonzales et al., 2006)

***(click to enlarge)

ESS=Eastern Senegal Speakers; Peu=Peulh; Ful=Fulbe; Wol=Wolof; Nal=Nalu; Bal=Balanta; Pap=Papel; Dio=Diola; Bij=Bijago; Lim=Limba; Tem=Temne; Mae=Mandenka; Bab=Bambara; Mal=Malinke ;Men=Mende; Lok=Loko; Yor=Yoruba; Bas=Bassa; Bam=Bamileke; Bak=Bakaka; Ewo=Ewondo; Fal=Fali; Tup=Tupuri; Tal=Tali; Tua=Tuareg; Hau=Hausa; Maa=Mandara; Pod=Podokwo; Uld=Ouldeme; Dab=Daba. See also this page for Upper Guinean ethnic groups. Source: Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Mauritania and Mali and their Genetic Relationship to Other Western Africa Populations (Gonzales et al., 2006)

***(click to enlarge)

Mitochondrial DNA genetic diversity among four ethnic groups in Sierra Leone. (Jackson et al., 2005)

***(click to enlarge)

Human Y chromosome haplogroup R-V88 – a paternal genetic record of early mid Holocene trans-Saharan connections and the spread of Chadic languages (Cruciani et al. 2010)

***

Human Y chromosome haplogroup R-V88 – a paternal genetic record of early mid Holocene trans-Saharan connections and the spread of Chadic languages (Cruciani et al. 2010)

Hi Fonte,

The additional files of the researched paper on trans-Saharan patrilineages (D’Atanasio et al, 2018), revealed the following frequencies and distributions for the haplogroup E1b-Z15939 as follows:

5.56% for the Asni Berber (n=54)

50% for the Fulani of Nigeria (North) (n=32)

3,33% for Burkinabe (n=30)

22,73% for Tuareg from Niger (n=22)

15,19% for Fulani from Cameroon (North/Chad) (n=79)

1,22% for Mandara from Cameroon (n=82)

25% for the Mandinka from Senegal (n=16)

36,36% for Gambian from Gambia (n=55)

14,29% for Mende from Sierra Leone (n=42)

Further inspection of the Yfull tree shows that the Gambian, the Mende samples, the Mexican sample (from Poznick et al., 2016), as well as the Mandinka samples (from the HGDP panel) aren’t E1b-CTS9883, but belong to deeper and diversified subclades of E1b-Z15939 (=E-CTS9883). Their total is 31. It appears that they have mixed the 4 Senegalese Mandinka samples as part of Gambia.

https://www.yfull.com/tree/E-CTS9883/

Consequently, we don’t know yet how the Fulani and the Tuareg samples cluster because NGS (Next-Generation sequencing) wasn’t produced on them. Given the connection between the two groups and what their autosomal DNA has revealed in the last decade or so, it is an interesting line of research. As you showed, in all of the published studies (and private test results) where the Fulani samples from various communities have been analyzed, their autosomal DNA systematically reveals a North African (“Maghrebi”) component which is widely distributed and stable.

Similarly, in 2012, geneticist Razib Khan concluded that the West Eurasian component of Fulanis that’s commonly observed in admixture analyses (Henn, 2012) is hardly ever found in its “pure” form in the present-day North African populations. They display a “Near Eastern” component which increases as we move east from NW Africa. In his opinion, this component likely arrived in NW Africa sometime between the Classical Antiquity and Islamic periods. This suggests that the “Maghrebi” component of Fulanis must be older – approximately 2000 years old.

Lastly, he hypothesizes that the source of the Fulanis’ Eurasian component could be either the Tuareg people or perhaps a similar, closely related population, who are likely to have this Maghrebi admixture in higher proportions than any other NW African group.

The rapid and recent expansion of E1b-M183 (M81) in NW Africa, as evidenced by the paper from Neus Solé-Morata et al., 2016, would corroborate Khan’s hypothesis. E1b-M81 is rare among Fulani, but their old admixture suggests some type of genetic drift, at some point, which would have repercussions in the Y-DNA and/or mtDNA. Only the findings from your paper reveal lineages among the Fula that are much older than the recent expansion of E1b-M81 and converge with present-day populations from the Sahara and not those from the Mediterranean coastal areas of NW Africa.

The author D’Atanasio suggests that E-Z15939 originated during the last Green Sahara period (10,000-5,000 years ago), possibly in a region of the “Green Sahara” that is now occupied by the desert and probably in a “Green Saharan” population that then split between Northern and sub-Saharan Africa. The authors plan on analyzing whole genome sequences for different Fulbe and Tuareg populations in the near future, so we may learn more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing these fascinating findings! Very exciting also that the authors of this study (“The peopling of the last Green Sahara revealed by high-coverage resequencing of trans-Saharan patrilineages”) plan to do a follow-up! Looking forward to their new insights.

I have been struck especially by this statement from their 2018 paper:

As you yourself once told me in an earlier comment:

I find this extremely intriguing. As these relatively recent ancestral connections between western Fula and eastern (Hausa-)Fulani also came to light during my survey of AncestryDNA results for Fula people. As well as my DNA matches survey among Cape Verdeans. In combination with traditional family history it may very well serve to corroborate clan lineages along the male line I imagine. See also:

https://tracingafricanroots.com/west-african-results-ii-2013-2018/

https://tracingafricanroots.com/2018/12/17/dna-matches-reported-for-50-cape-verdeans-on-ancestrydna-part-1/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it is intriguing, even more so when considering how old and high on the tree, this particular clade is.

Initially, at the time of the publication of this paper, I didn’t know that NGS’s results hadn’t been produced on Fulbe samples and also, I hadn’t realized that the other West African groups that they are referring to, and who have been tested using NGS, actually belong to different and more recent downstream subclades.

So it may be too early to come to a definitive, complete answer. Dealing with the time span of several thousands of years with the current limited data (not even tested with NGS), as you can imagine, it is difficult to pinpoint a precise origin for the coalescence of this clade. The lack of ancient DNA from this region and the neighboring ones is another issue. In addition, the recent bidirectional migrations of nomadic Fulbe communities can complicate things even more. In any case, we’ll see.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know if you have mentioned the distribution of various Y-DNA haplogroups in relation with Upper Guinea, lower Guinea and West-Central Africa. Following the refinement of major haplogroups with the help of NGS, different distinctions can be made.

E1b-Z15939 (including its subclades) is restricted to the Sahel and Senegambia. The subclades of E1b-U175 (E-U290) and E1b-M191 (E-U174) are strongly represented among Bantu people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not yet blogged a great deal about paternal haplogroups. As I myself happen to have an European male haplogroup (I1*). I have been aware of some studies though about male haplogroups among Guineans (Bissau) and Cape Verdeans. Possibly somewhat dated but still interesting outcomes. The Guinean study also includes 59 Fula samples! And the authors state that they found: “North African influence in E3b1-M78”.

Y-chromosomal diversity in the population of Guinea-Bissau: a multiethnic perspective (Rosa et al, 2007)

See also this overview:

For Cape Verdeans like wise a minor possibly North African origin is detected in these papers:

Y-chromosome lineages in Cabo Verde Islands witness the diverse geographic origin of its first male settlers. (Gonçalves et al., 2003)

The Admixture Structure and Genetic Variation of the Archipelago of Cape Verde and Its Implications for Admixture Mapping Studies (Beleza et al., 2012)

See also this overview taken from the 2003 paper:

Quite likely some of these possibly “North African” haplogroups have been passed on by Fula ancestors for Cape Verdeans. But probably also other ancestral scenario’s (Portuguese, Sephardi Jews etc.) might apply.

I have blogged about these findings in relation to autosomal admixture results for Cape verdeans and their North African DNA matches on Ancestry on this page (section 3):

https://tracingafricanroots.com/2018/12/17/dna-matches-reported-for-50-cape-verdeans-on-ancestrydna-part-1/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting!

E1b-M78 has many important lineages. Briefly, this is what the authors (D’Atanasio, 2018) suggest:

“E-M78 is a widespread lineage, with significant frequencies in Africa, Europe and the Middle East [33, 34]. Within the African continent, three E-M78 sub-clades (E-V22, E-V12 and E-V264) show different frequencies in different regions.

E-V22 is mainly an eastern African sub-haplogroup, with frequencies of more than 80 % in the Saho population from Eritrea, but it has also been reported in Egypt and Morocco [34–36].

E-V12 is relatively frequent in northern and eastern Africa, but it has also been reported outside Africa at lower frequencies [33–35]. The vast majority of the eastern African E-V12 chromosomes belong to the internal clade E-V32, which has also been observed in northern and central Africa at very low frequencies [12, 33–35].

E-V264 is subdivided into two sub-clades: E-V65, common in northern Africa; and E-V259, which includes few central African chromosomes [33–35]. ”

In Europe, E1b-V13 is the main European subclade of E1b-M78.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_E-V68#E-V13

E1b-M81 is typically the most dominant haplogroup in Northwest Africa suggesting NW African ancestry via the male line, although, of course, there are other lineages as well such as E1b-V65. The distribution of E1b-M78 tends to increase in Northeast Africa, but declines in NW Africa.

Considering how old those studies are, I wonder how much more refined the terminal clade of those samples could be, using NGS.

I wouldn’t be surprised if some of those Cape Verdean samples would turn out to be E1b-V13. In the case of Guineans (Bissau), it’s not clear. E1b-M78* is just too old and high on the tree. I would guess either distant Northeast African, North African, or recent European ancestry.

LikeLiked by 1 person