In October 2015 I published my first preliminary survey findings based on 23 Cape Verdean AncestryDNA results (see this link). Right now, almost three years later, I have managed to collect a sample group which is four times greater. Consisting of no less than 100 AncestryDNA results of fully Cape Verdean-descended persons! Even though this quadrupled sample size is obviously still limited it will most likely provide a greater insight in the various ways how “Caboverdeanidade” can be described. Genetically speaking that is. And obviously when applying the regional AncestryDNA format, with all its enhanced features as well as its inherent shortcomings 😉

***

Click on this banner to reach Cape Verde DNA, Inc: the biggest online community of Cape Verdean Genealogy & DNA enthusiasts! On Augustus 4 & 5 a pioneering Cape Verde DNA and Genealogy Conference will be held! See this link for more details.

***

In this blog post I will discuss the main differences with my previous findings from 2015, which were focused on the African breakdown solely. And in addition I will also present some new statistics and background information on the European and other non-African origins of Cape Verdeans as reported by AncestryDNA. Below an overview of all the topics I will cover:

- Background details of my 100 Cape Verdean survey participants

- To be Cape Verdean is to be mixed?

- Upper Guinean roots = “Senegal” + “Mali”

- Beyond Upper Guinea: valid outcomes or misreading by AncestryDNA?

- European breakdown reflecting mostly Portuguese ancestry?

- “Africa North”, “Middle East”, “European Jewish” and other minor regional scores

- Upcoming update of AncestryDNA’s Ethnicity Estimates

Follow these links for my complete survey data & research methodology:

Table 1 (click to enlarge)

***

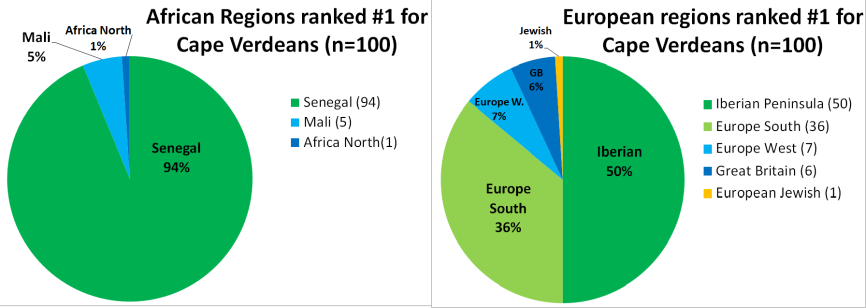

Chart 1 (click to enlarge)

This frequency of regions being ranked #1 (regions with the highest amount in either the African or European breakdown) is perhaps the best indicator of the main ancestral components for my Cape Verdean survey group. However only in an extra pronounced degree. For more nuance see the group averages in the next sections.

***

Screenshots of individual results (rightclick and open in new tab to enlarge; island origins shown below)

More charts and analysis when you continue reading!

***

1) Background details of my 100 Cape Verdean survey participants

Table 2 (click to enlarge)

***

I would first of all like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to all my survey participants! Without their kind willingness to share their results with me my research would not have been possible! In fact aside from giving me access to their results many people also shared useful and very interesting details about their family history with me in PM’s. As far as I was able to verify through such contact or also through public family trees and other publicly available information all my survey participants are of fully Cape Verdean descent. Although I did not have absolute certainty in all cases (see column AK in my spread sheet).1

That is going back on all lines for at least 2 generations. In other words all 4 grandparents being Cape Verde-born. Migration plays a key role in the Cape Verdean experience and therefore “Cape Verdean” is somewhat loosely defined in my survey. For the sake of my research and just to be practical I had to draw the line somewhere. But I never intended for this 4 grandparents criterium to be seen as any kind of absolute measure of Caboverdeanidade.2 Especially for multi-generational Cape Verdean-Americans I had to be lenient in a few cases and also take into consideration how some families amazingly already have been established in the USA for more than 3 generations! Provided that all 8 great grandparents or all 16 great-great grandparents were Cape Verde-born these persons still count as 100% “Cape Verdean” in my book. At least genetically speaking and within the context of my survey 😉

***

***

Again despite having been provided with abundant background details for most of my survey participants I do not pretend to have an exact or 100% complete overview of their origins! Afterall some people might also themselves not be fully informed or even misinformed about their recent ancestry. Still the background details I have been able to collect are very insightful in themselves already I believe. Possibly with wider implications even in some aspects. Table 2 highlights that Cape Verdean-Americans form the majority of my survey group, numbering atleast 60 out of 100. Not that surprising given that Ancestry.com is an American company and the USA is often said to host the biggest part of the Cape Verdean Diaspora.

Interestingly the greatest group of these Cape Verdean Americans still is only 1 generation removed from having Cape Verdean roots. That is 34 survey participants have two Cape Verde-born parents, while being USA-born themselves. For 19 USA-born persons in my survey it was rather a gap of two generations with their Cape Verdean roots. As they also had USA-born parents, who in turn had Cape Verde-born parents. Very intriguingly atleast 7 persons are included in my survey who confirmed to me that they were of fully Cape Verdean descent on all lines. Despite having USA-born grandparents and even USA-born great-grandparents in a few cases! A testament to the admirable ways Cape Verdean American communities have been kept together across the generations! Even when such consistent endogamy on all lines might not per se have been the rule.

Going by public family trees and what was confirmed to me in PM’s the earliest birthdate of a USA-born Cape Verdean-American ancestor is 1871, among my survey participants. Which is quite extraordinary in itself but I suppose even earlier birthdates might be forthcoming given diligent family tree research. Also keeping in mind the longstanding presence of Cape Verdeans in America: the first Africans to migrate to the USA out of their free will and even at times on self-owned ships! A truly awe-inspiring saga!

Aside from my Cape Verdean American survey participants I still did manage to also include atleast 27 Cape Verde-born persons within my survey. Although a minority they still make up more than a quarter of my survey group and provide a very useful benchmark to verify my overall findings. Their island origins within Cape Verde also being more diverse on average. Cape Verdean Americans mostly hailing from Brava and Fogo as well as São Nicolau and Santo Antão. But these Cape Verde-born samples also being from Boavista, Maio, Sal, Santiago and São Vicente. Many of these Cape Verde-born survey participants are however also long term citizens of the USA. And may therefore naturally also self-identify as Cape Verdean-American, even if I have not labeled them as such in table 2 😉

As a great illustration of the extent of Cape Verdean migrations my survey also contains the results of persons who are part of the Cape Verdean Diapora in the Netherlands, Portugal, Brazil, Angola, Guiné Bissau, São Tomé & Principe, Senegal and even the Ivory Coast. I actually did not always include these persons in my main survey findings as some of them were only partially of Cape Verdean descent (like myself). This goes especially for people of recently mixed Angolan and Guinean descent. Again only for the sake of my research purposes: establishing the main ancestral components within the Cape Verdean genepool.

Genetic Communities a.k.a. Migrations on Ancestry

Figure 1 (click to enlarge)

Because of the ongoing growth of Ancestry’s customer database the number of people being assigned to their various migrations or genetic communities is constantly increasing. At the moment of writing this blog post the most recent number being mentioned for the “Portuguese Islander” migration was no less than 5,797! As an indication of relative endogamy most Cape Verdean Ancestry testers will tend to have hundreds if not thousands of matches within this group. I suppose it also highlights how DNA testing has become really popular among Cape Verdean-Americans!

***

In table 2 we can also see the frequency of “migrations” a.k.a. genetic communities my survey participants have been assigned to by Ancestry. This migration feature has been integrated within Ancestry’s Ethnicity Estimates since 2017. It is based on having a strong genetic connection (measured by IBD matches above a given threshold, possibly >12 cM) to a certain group of people. These genetic clusters or networks of interrelated people are given greater context by way of their average ethnicity scores, family trees and implied migration histories. Even when it does have its shortcomings I do find that Ancestry’s migration tool is reasonably predictive and quite useful! It provides a great way to sort out your Cape Verdean related DNA matches. Even if many of these matches might actually be of mixed descent and also not all of your Cape Verdean related matches might be covered.3 For more details see also:

- Help & Tips in regards to Ancestry’s migration/genetic community tool (Ancestry)

- Genetic Communities™ White Paper (Ancestry)

- Clustering of 770,000 genomes reveals post-colonial population structure of North America (Nature, 2017)

As expected the socalled “Portuguese Islander” migration shown in figure 1 is appearing for a greater majority (62/88=70%) of my survey participants. Even when for 23 people no such assigment was given, inspite of being of verified Cape Verdean descent! I suppose this outcome is indicating that Ancestry’s migration tool is still a work under progress. I also find it rather unfortunate that such a potentially misleading name has been chosen for this migration. I strongly urge Ancestry to change the labeling of the socalled “Portuguese Islander” migration into “Cape Verdeans”. This will be much more appropriate given that from what I have seen the vast majority of people being assigned to this genetic community share common Cape Verdean lineage from the last 4/5 generations or so. This network of DNA connections arising because of kinship which originated in Cape Verde itself aside from occasional overlap with actual Portuguese islanders (Azores & Madeira) who already have separate migrations in place on Ancestry.

In addition a considerable number (16/88) of my Cape Verdean survey participants are also part of the “Portuguese” migration, indicative of recent Portuguese lineage to be traced back within the last 4/5 generations or so. Which is in line with relatively recent Portuguese ancestors from either the 1900’s or the 1800’s. Even when earlier Portuguese ancestry from the 1400’s-1700’s will not be included this outcome is very useful therefore. Interestingly for one single survey participant from Brava also the “Spaniards, Cubans, Dominicans & Venezuelans” migration appeared along with “Portuguese” and “Portuguese Islander”. Most likely suggesting Spanish lineage although perhaps also caused by partial Portuguese or Galician ancestry among his DNA matches within this genetic community. Even when it is true that the European origins of Cape Verdeans also include some degree of non-Iberian lineage, it is probably quite telling that I did not encounter any other European migration among my survey participants. Especially given that this migration tool is arguably most fine scaled for the European continent (aside from the USA). The European regional breakdown on AncestryDNA offers more clues on the degree of Portuguese lineage for my Cape Verdean survey participants. I will discuss this topic further in section 5.

The only other migration being reported aside from “Portuguese Islander”, “Portuguese” and “Spaniards” was “African Caribbean”. This only happened once though for one single survey participant (born in Santo Antão). Somewhat surprising and atypical. But more easily understood when keeping in mind that a strong genetic connection can also be the result of reverse geneflow. In other words instead of suggesting a possible Caribbean ancestor for my Cape Verdean survey participant it is probably much more likely that several Caribbean people belonging to this genetic community either have recent Cape Verdean ancestry or shared African or Portuguese lineage.4 The latter scenario perhaps most plausible generally speaking. Given the well documented history of Portuguese contract labourers in the Caribbean, often hailing from Madeira. I will revisit this theme of unexpected Caribbean matches in an upcoming blogpost in which I will analyze the DNA matches being reported for 50 of my Cape Verdean survey participants.

2) To be Cape Verdean is to be mixed?

Figure 2 (click to enlarge)

This limited selection is merely intended to illustrate the admixture range across the islands. Obviously individual variation will not always correspond with the “averages”. Also within each island there will be a wide range of admixture proportions therefore.

Chart 2 (click to enlarge)

The number in each bar represents how many survey participants had African admixture scores within that range. 74 people (41+33) had African scores of in between 40%-60%. Still a considerable number of people showed more widely ranging African admixture.

***

Table 3 (click to enlarge)

The island origins of my survey participants are not based on a 4 grand parents criterium per se. As many people were not fully aware. See also footnote 6. Still insightful variation being shown. The African admixture ranges (min. – max.) were as follows: Barlavento (43%-59%); Brava and Fogo (19%-61%) ; Santiago (62%-86%).

***

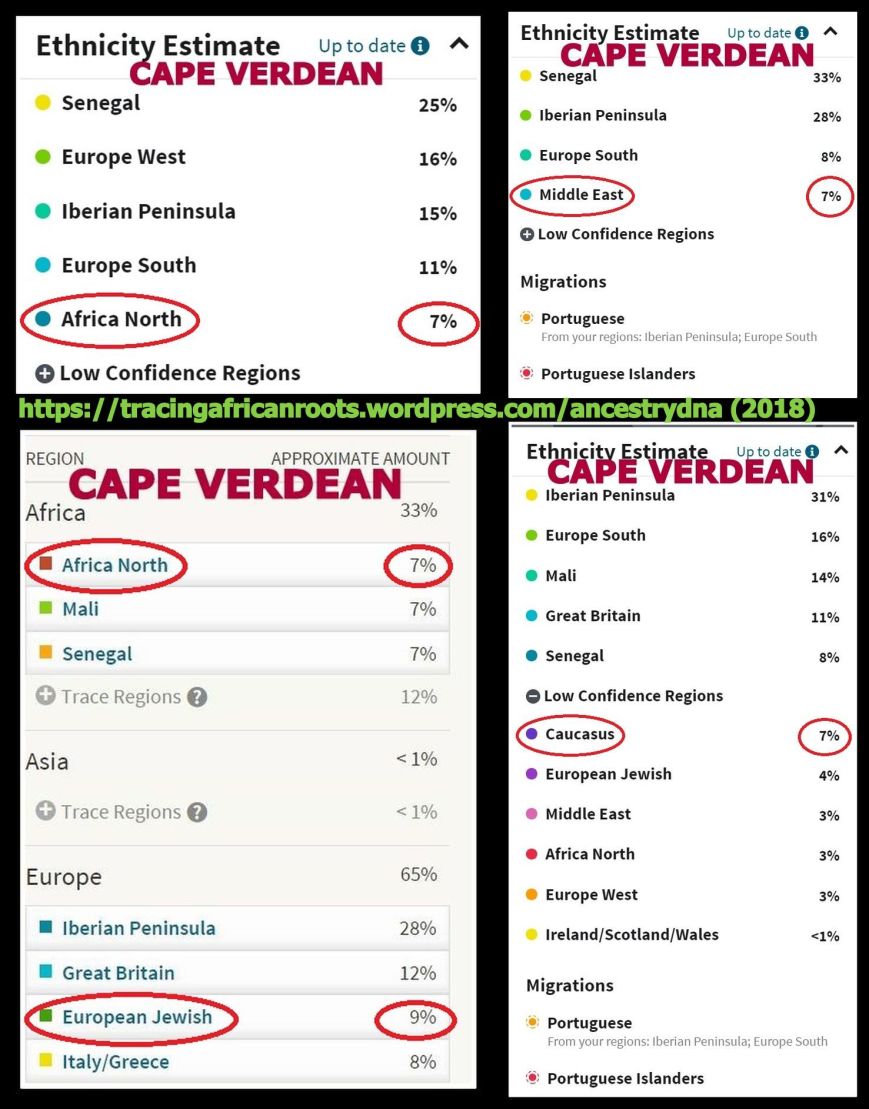

Table 1 & chart 1 posted in the very beginning of this blog article already demonstrated that all of my Cape Verdean survey participants show a considerable degree of continental admixture. Principally a mix of Upper Guinean DNA (“Senegal” + “Mali”) & Southern European DNA (“Iberian Peninsula” and “Europe South”) although other minor ancestral components are also frequently reported. In particular “Africa North”, “Middle East” and “European Jewish” admixture. These outcomes will be discussed in following sections.

The group averages are displaying a remarkable balance between African & European admixture. Practically 50/50 proportions. This thorough racial blending marks a key aspect of not only Cape Verdean genetics but also Cape Verdean creolized culture and Caboverdianidade. One should be careful though to exclusively equate the Creole a.k.a. Crioulo identity of all Cape Verdeans with being racially mixed per se, or at least not in balanced proportions. The all-inclusive Crioulo identity of Cape Verdeans (regardless of racial appearance or DNA results) is often misunderstood by outsiders which causes them to apply it for inappropriate and potentially divisive racial classifications5. See also:

- From Creole to African (Tracing African Roots)

As shown directly above there is actually quite some individual variation hiding behind the group averages. In particular along specific Cape Verdean island origins6. In chart 2 we can verify that indeed the range of 40%-60% African admixture is by far the most common among my survey group (combined almost 75% of the group). However a considerable minority is showing less balanced admixture proportions going either way. With a minimum score of 19% African for a person with island origins from Brava and a maximum score of 86% African for a person with most likely island origins from Santiago7. Strictly speaking in terms of socalled Sub-Saharan African (SSA) DNA the sample from Brava actually is 13% SSA after leaving out the 6% “Africa North” score (see figure 2).

Despite minimal sample size for the most part and overrepresentation of certain islands the inter-island variation shown in table 3 is quite insightful already. We can verify that my survey participants from Brava had the lowest group average for African admixture. Around 40% but often also lower in individual cases. As was also the case in 2015 (see this chart) my survey is somewhat biased towards island origins from Brava & Fogo. Because most Cape Verdean Americans tend to be from those islands (see this link). I did however also expand on my Barlavento sampling (Santo Antão, São Nicolau and São Vicente). Their group averages being closest in line with my overall findings of balanced admixture proportions. A few survey participants had partial island origins from Boavista. But because they were mixed with other island origins I couldn’t include them in table 3. Their average African admixture was somewhat increased, around 60%. Interestingly my only survey participant from Maio also showed an increased level of African admixture of 68%.

A major difference between my previous survey findings from 2015 is that I am now able to offer an improved perspective on Cape Verdean population structure due to the inclusion also of a few Santiago examples. Santiago is the biggest and most populated island of Cape Verde. Because of its early settlement history it is arguably together with Fogo also the birth place of Cape Verdean identity and culture. Despite overall commonalities each of the nine inhabited islands of Cape Verde did eventually develop a distinctive (sub)-culture of its own. Due to relative geographical isolation for the most part. Most clearly noticeable perhaps by the various island-specific dialects of the Crioulo language. Santiago is often said to have retained its African heritage the best, epitomized by its Badiu identity. The higher than average African admixture scores reported for my survey participants from Santiago are therefore in line with expectations. Despite the minimal sample size this outcome does underline that Cape Verdean genetics cannot be generalized as simply “mixed”8 as there is underlying substructure as well. Not only between islands but probably also within island populations.

Confirming and complementing previous DNA studies?

Chart 3 (click to enlarge)

This chart is taken from Beleza et al. (2013, p.2). Based on 685 samples from 6 Cape Verdean islands. Santo Antão + São Vicente + São Nicolau (n=192), Boavista (n=27), Santiago (n=172), Fogo (n=129) (source). It shows a similar distribution of African admixture as my own survey results (chart 2, n=100). Also including similar minimum (23.5%) and maximum (87.9%) values for African admixture (Beleza et al., 2013, p.2). At the the same time it also clearly shows substructure as can be seen from the second peak around 70% African ancestry.

***

Chart 4 (click to enlarge)

This chart is taken from Beleza et al. (2012, p.5). Based on 646 samples from 6 Cape Verdean islands. Santo Antão (n=136; mean 56%), São Vicente (n=84; mean 56%), São Nicolau (n=110; mean 56%), Boavista (n=66; mean 59%), Santiago (n=124; mean 65%), Fogo (n=126; mean 53%) (source) Clearly higher African admixture for the Santiago samples, on average. While the African proportions for the other islands are more similar and balanced. But the one for Fogo being slightly lower than the rest. Very similar to my own findings shown in table 3.

***

Chart 5 (click to enlarge)

This chart is taken from Verdu et al. (p.2531, 2017). It is based on 44 samples drawn exclusively from Santiago. It demonstrates how Santiago also shows a wide admixture spectrum even when on average its African genetic heritage is more pronounced than on the other islands. No statistical details are provided in this study but it seems apparent that African admixture values of around 80% were most frequent.

***

Various important and insightful studies have already been published on Cape Verdean genetics. The charts being featured directly above are taken from the most recent studies dealing with autosomal genetics (covering the whole genome) in particular. Therefore most suitable to compare with my own findings which are likewise based on autosomal DNA analysis. Eventhough there do exist some differences in methodology. AncestryDNA’s genotyping probably being most up-to-date and producing more high resolution and regionally varied results9. Highly recommended to read these papers yourself for more details:

- The Admixture Structure and Genetic Variation of the Archipelago of Cape Verde and Its Implications for Admixture Mapping Studies (Beleza et al., 2012)

- Genetic Architecture of Skin and Eye Color in an African-European Admixed Population (Beleza et al., 2013)

- Parallel Trajectories of Genetic and Linguistic Admixture in a Genetically Admixed Creole Population (Verdu et al., 2017)

For an overview including also haplogroup studies see:

- DNA Evidence (Cabo Verde Raizes Na Africa)

I will revisit the fascinating research outcomes of these studies also in the following sections. Just focusing on the theme of admixture proportions I believe my own survey findings are broadly in line with these previous studies. And therefore arguably also corroborated by them. We can see this most clearly in charts 3 & 4 which feature a comparable distribution of African admixture as shown in chart 2 and table 3, based on my survey data. The most common admixture brackets lying in between 40%-60%. The higher median value of 58% in Beleza et al. (2012 & 2013) to be explained by a much greater inclusion of Santiago samples (124/646 and 176/685) when compared with my survey (3/100) which had a median value of 48% instead. Beleza et al. (2012 & 2013) therefore being better equipped to uncover substructure in Cape Verdean population although my survey findings do hint at this as well.

Then again I also believe that my survey data are complementing these previous studies because of my inclusion of samples from Brava. Even though covering most of Cape Verde’s islands, Brava was not researched in Beleza et al. (2012 & 2013). Also Maio was left out while being represented by one single sample in my survey. The Fogo and Barlavento island origins covered by my survey mirror those found within Beleza et al. (2012 & 2013) but the latter studies do have an additional advantage of also including a significant number of samples from not only Santiago but also Boavista.

Verdu et al. (2017) is only making use of samples taken from Santiago (n=44, not per se with 4 grand parents born in Santiago though, p.2536). But despite being smaller in size their dataset does seem even more illustrative of Santiago’s admixture range than Beleza et al. (2012 & 2013). Although regrettably no specific admixture statistics are given in their article, based on chart 5 it seems an African admixture range of around 80% would have been most frequent. With a maximum value of possibly just over 90% African. Slightly higher than what was obtained for the Santiago samples in Beleza et al. (2012, 2013): median of 74.4% and maximum value of 87.9%. All in all I think combining the sample sets from all these studies, incl. my survey data, might provide a more complete overview. My Brava findings being indicative of the lower admixture proportions to be found among Cape Verdeans as well. While Verdu at al. (2017) serving to underline the generally higher African admixture degree to be found in Santiago. Although noticeably not including a single sample of 100% African descent! I suppose such results might still be forthcoming for Cape Verdeans (with at least 4 Cape Verde-born grandparents) given wider and more targeted sampling. But the frequency of such results might be quite low.

Admixture mostly occurring in the 1500’s/1600’s or rather in the 1700’s/1800’s?

____________________

“As far as we know, Cape Verde is presently one of the most highly admixed populations resulting from the mixing of European and African parental contributions, and may be only paralleled by some regions in Brazil. Moreover, the comparison of African ancestry proportions calculated with X, Y-chromosome and autosomal markers confirms that admixture involved predominantly European men and African women, like in many other societies emerging from the Atlantic slave trade.” (Beleza et al. 2012, p. 9)

____________________

Table 4 (click to enlarge)

This table shows the proportion of enslaved people living in Cape Verde. Take notice that in 1731 a greater majority of Cape Verdeans had freed status (and probably already in the late 1600’s). Slavery did remain a reality for many people still but overall speaking they were a small minority of Cape Verde’s total population, less than 10% throughout the 1800’s. This provides a stark contrast with most other parts of the Afro-Diaspora. Source: “Crioulização em Cabo Verde e São Tomé e Príncipe: divergências históricas e identitária“, (Seibert, 2014, p.53)

*** Table 5 (click to enlarge)

This table is showing the racial composition of Cape Verde’s population across time (Branco=White; Mestiço=Mulatto; Negro=Black). Plus it also makes a distinction between enslaved black people (escravos) and black people with freed status (livres a.k.a. forro). Take note that the share of mixed people is steadily increasing but only reached a majority of the population in 1900!

***

This section is going to be speculative to some degree and may touch on a potentially sensitive topic. But I think this makes for a promising research field. Possibly to be explored in greater detail by a close study of European IBD matches for Cape Verdeans (see upcoming blog post). I think it is very relevant to pose questions about the exact time framing of European admixture. Because the popularization of personal DNA testing confronts many people among the Afro-Diaspora as well as Cape Verdeans with the question of how their generally racially admixed test results came to be. My finding of a relatively high frequency of the “Portuguese” migration being assigned to my Cape Verdean survey participants (16/88, see table 2) reinforces this research question. As this outcome seems to suggest a considerable Portuguese gene-flow occurring also in the last 4 or 5 generations. These Portuguese ancestors, even from the late 1800’s, are actually often still remembered in the family lore of many Cape Verdeans, as they were usually involved in either marriage or otherwise consensual unions with Cape Verdean women.

I fully understand and respect that given the brutal history of the Slavery Period as well as continued racism afterwards many Afro-Diasporans might not be inclined to learn more about their mixed European origins. Even if the possibility of this European ancestry (partially) dating from the Post-Slavery Period cannot be ruled out in advance. Muhammad Ali’s Irish great-grandfather makes for an intriguing example. Still other Afro-Diasporans will be more curious about their complete genetic make-up and how this might define them. Despite shared experiences one must also be careful to respect the localized context and different historical trajectories across the Afro-Diaspora. Instead of just letting one single perspective on inter-racial relationships overcloud things. This goes especially for Cape Verdeans who despite being part of the Afro-Diaspora in many aspects have a unique history of their own. And as a consequence their family trees & genealogy will usually not fit in well with simplistic generalizations. And even less so with ideologically charged assumptions arising from a specific USA context or an overly Americanized mindset.

As shown in the quote above from Beleza et al. (2012) certain generalizations are also being perpetuated in scientific papers. Which is not to say that their statement about Cape Verdean mixed genetics ultimately being the result of unions between African women and European men is factually wrong.10 I am pleading however for more nuance and a greater focus on events taking place on a micro-scale in order to arrive at historically accurate family narratives. As shown in table 4 more than 80% of Cape Verde’s population would no longer have been enslaved already in 1731. However going by table 5 the racially mixed segment (mestiço or mulatto) of Cape Verde’s population by that time was still a minority of around 30%! Combining both “facts” (based on sketchy census data naturally 😉 ) it seems to be implied that ongoing European geneflow taking place in the 1700’s & 1800’s would most likely not have involved unions with enslaved (mainland) African women at least not for the most part. But rather unions between in particular Portuguese men (probably especially exiled convicts or otherwise officials and seamen) and Cape Verdean women (either black or mixed) who usually might have hailed from families with freed status dating from several generations ago. No doubt given the colonial context some structural element of power imbalance (beyond gender) would still have been at play. Although individual agency (incl. by females) is also not to be ruled out. Either way such a scenario does differ from the circumstances in many other parts of the Afro-Diaspora at the same time.

In the first two centuries of Cape Verde’s settlement (1460-1660) the context of inter-racial unions could very well have been more similar to other parts of the Afro-Diaspora. The often violent circumstances prevailing in that era should naturally be fully acknowledged. Especially in order to deal with the socio-cultural repercussions in following time periods up till the present. Then again I would argue to still attempt to understand localized realities from the perspective of someone who actually would have lived in that time & place. A pragmatic and open-minded stance instead of constant indignation being more likely to lead to genuine learning about your origins. You might then of course still encounter both negative and positive aspects. However also often unexpected details might turn up enriching your research and making it more insightful. Things are often far more complex, inter-connected and intricate than you might assume at first.

The extent of admixture among the nascent Cape Verdean population in the 1500’s-1600’s would have been quite considerable back then already. As confirmed not only by sketchy census reports but also historical testimony by colonial officials, visiting travelers etc.. Their accounts about widespread concubinage with African women and manumission of mixed-race offspring are recommended reading in order to reach greater understanding about the nature of inter-racial unions back then. Even when they might not tell the whole story. Either way more research needs to be done to establish in which time period European geneflow might have had the most impact on Cape Verdean genetics. As always I believe that a multi-disciplinary approach may deliver the best results instead of relying on one-sided and preconceived notions. Including a good grasp on local history, personal genealogy as well as DNA testing, not only in regards to admixture analysis and haplogroups but also in particular IBD matches. For further discussion and also a fascinating parallel with the question of European geneflow among African Americans see:

- Black/White Interracial Marriage Trends, 1850–2000 (A. Gullickson, 2006) (see p.3 for an insightful chart)

- Cape Verde Slave Census of 1856 (part 1) (Tracing African Roots)

- Historical demography of Cape Verde (Cabo Verde: Raizes Na Africa)

3) Upper Guinean roots = “Senegal” + “Mali”

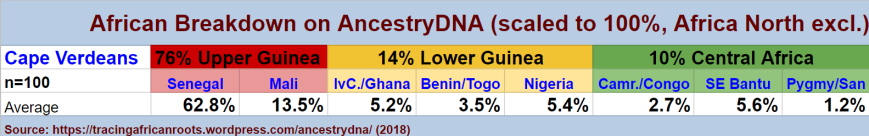

Table 6 (click to enlarge)

Despite the quadrupling of my sample size this scaled African breakdown showing a predominance of regions associated with Upper Guinea, is still practically the same as in 2015, see this chart (n=23). Highlighting the relative homogeneity of Cape Verde’s African regional roots.

***

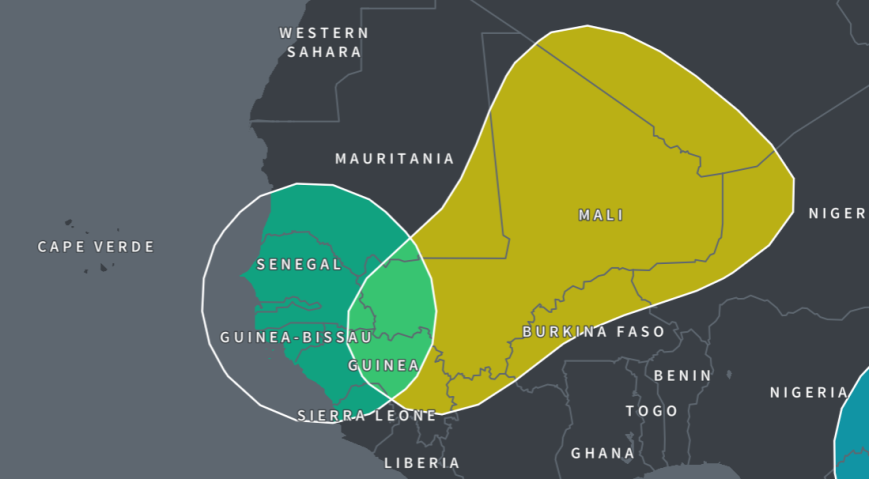

Figure 3 (click to enlarge)

This screenshot shows the areas where the “Senegal” and “Mali” regions can be found according to Ancestry’s updated info. Take note how “Senegal” expands all the way into Sierra Leone. While according to my survey findings “Mali” actually also is frequently reported for people in Senegambia, Guinea Bissau/Conakry and again Sierra Leone.

***

Figure 4 (click to enlarge)

Take note how socalled “Senegal” is in fact reported for people all across Upper Guinea, as far south as Sierra Leone! The same goes for “Mali” which also is reported in substantial amounts for all of these African samples. And therefore this region can also be suggestive of lineage from various countries in the wider area and not just Mali!

***

Compared with my previous survey findings (n=23) from 2015 the Upper Guinean predominance (as measured by “Senegal” and “Mali”) has been remarkably consistent among Cape Verdean AncestryDNA results. There is actually very little difference between table 6 and a similar table I blogged about in 2015! Inspite the fact that my survey has considerably expanded in sample size. Also when comparing my current survey findings for Cape Verdeans with those with other parts from the Afro-Diaspora this Upper Guinean predominance remains a singular and distinguishing feature. I suppose this speaks of the robustness of this outcome despite inherent shortcomings of AncestryDNA’s regional set-up. See also:

- Update: Afro-Diasporan AncestryDNA Survey (part 1) (Tracing African Roots)

In 2015 I already discussed in greater detail how basically both “Senegal” and “Mali” are genetic components which may have been inherited from many various Upper Guinean ethnic groups. Despite the modernday country name labeling these regions are by no means limited to only Senegal or Mali! My ongoing survey of African AncestryDNA results allows me to affirm this with even greater confidence. In particular the results from Upper Guinean countries such as Senegal, Gambia, Guiné Bissau, Guinea Conakry, Mali and Sierra Leone are clearly demonstrating the border crossing and overlapping nature of AncestryDNA’s regions. As shown in figures 3 & 4 for example. This is to be explained by ancient migrations & shared origins across the wider area, irrespective of modernday country borders or (fluid) ethnic identity. Most African countries are afterall colonial creations! The socalled “Senegal” region showing a remarkable and fitting similarity with the historical area of “Guiné de Cabo Verde“, once stretching from the Senegal river in the north to the Sierra Leone peninsula in the south (see this map). For more discussion:

One minor but still noteworthy difference with my surveyfindings in 2015 is that aside from “Senegal” (94/100) in a few cases also “Mali” (5/100) was reported as the biggest region within the African breakdown. And 1 single time even “”Africa North” (see chart 1). The top-ranking frequency of “Senegal” (94%) is still overwhelming though and its predominant share of the scaled African breakdown has also stayed very consistent (around 62%). The generally secondary importance of “Mali” remains the same as already established in 2015 (between 12%-14% of the total African breakdown, see table 6). It is probably also telling that these somewhat atypical top ranking “Mali” results were generally reported for people with lower than average total amounts of African admixture. Possibly influencing the ability of AncestryDNA to make a correct distinction between the overlapping regions of “Senegal” and “Mali”.

In 2015 I explored some possible scenario’s involving not only genuine Malian lineage but also an ancestral connection with Guinea Conakry and Sierra Leone based on the results of especially Mexicans and their shared “Zape” heritage with Cape Verdeans. Having seen and analyzed many more AncestryDNA results in the meanwhile I would currently say follow-up research based on DNA matches is probably the best way forward (see this link for a tutorial, as well as upcoming blogpost). An exact interpretation of “Mali” scores still being very precarious. As this region is probably best to be seen as a generic proxy for Upper Guinean lineage. Probably even more so after the upcoming update. See section 7 for continued discussion.

Most recent research on Upper Guinean roots of Cape Verdeans

Table 7 (click to enlarge)

This table is taken from my ongoing African survey of AncestryDNA results. Despite very limited sample size it is still already telling that the Cape Verdean group average for “Senegal” (scaled to 100%!) is in between samples from Senegal and Gambia and one single sample from Guiné Bissau.

***

In 2015 my survey findings established for the first time (as far as I am aware) that autosomally speaking the African part of Cape Verdeans can be characterized as predominantly Upper Guinean (~75%) At that time I did not however have any other AncestryDNA results from actual Upper Guineans to compare with. Luckily an increasing number of Africans are taking DNA tests nowadays. Which is why I am now able to compile table 7 which provides a benchmark of sorts to see how the scaled African breakdown of Cape Verdeans fits in with neighbouring countries from Upper Guinea. Despite the very limited sample size for most of the separate nationalities this relevant array of samples does still seem to contribute to the robustness and coherency of my overall data set. Although I wish I could have included a couple more results from especially Guiné Bissau. The one single Guinean sample in my survey actually being of mixed background, a.k.a. mestiço. Still it seems quite telling already that the group average for “Senegal” as well as “Mali” among my 100 Cape Verdean survey participants is quite similar to the ones for actual Senegalese and Gambians. As well as similar to the group averages for 43 Fula samples from various countries (incl. Guinea Conakry). But not perfectly so. The somewhat increased group averages for other regions among my Cape Verdean survey participants perhaps being an indication of additional origins from other parts of Africa. This will be discussed in the following section 4. For more details see:

- African AncestryDNA results (spreadsheet with individual results)

- Upper Guinean AncestryDNA results

- Youtube video showing the results for a person from Guiné Bissau

Chart 6 (click to enlarge)

This chart is taken from Verdu et al. (p.2530, 2017). At K=4 four different putative ancestral clusters are being revealed. And very intriguingly it turns out that the selected Gambian samples (red) are a better match than Senegalese samples (orange) to capture Cape Verde’s Upper Guinean ancestry.

***

In chart 6 an extremely fine-scaled research outcome is displayed which I have been highly anticipating for several years already! It is taken from an excellent study which also analyzes the correlation between African admixture and African influenced linguistics among 44 samples recruited in Santiago (Verdu et al., 2017). It shows a socalled ADMIXTURE run comparing 44 Cape Verdean samples with 109 Gambian Mandinka samples and 22 Senegalese Mandenka samples as well as European samples from Iberia, France and Great Britain. At K=4 four different putative ancestral clusters are being revealed. And very intriguingly it turns out that the selected Gambian samples (red) are a better match than the Senegalese samples (orange) to capture Cape Verde’s Upper Guinean ancestry!

Naturally Cape Verde’s actual African origins include many more ethnic groups than just these two very closely interrelated Mandé subgroups. Intuitively this outcome does make sense though because of Gambia being geographically closer to Guiné Bissau. This latter country arguably being the best proxy for Cape Verde’s overall Upper Guinean heritage, even if not exclusively so. Although I suppose it might also be that simply because of the greater number of Gambian samples the odds of genetic similarity were also increased. The output of this type of admixture analysis is naturally predetermined to a great degree by the input. Actually a comparison with Mende samples from Sierra Leone (again a Mandé speaking subgroup, take note of the spelling 😉 ) is also being made in the study (fig. 1A). And according to the authors “The Gambian Mandinka and Senegalese Mandenka are genetically closer to Cape Verdeans than are the Sierra Leone Mende” ((Verdu et al., p.2430). Which again seems right although I suspect that for historical reasons the Temne from northern Sierra Leone might have made a better fitting proxy than the Mende from southern Sierra Leone. See also:

- Maps of various Mandé speaking groups (scroll down for it) (Tracing African Roots)

- Top 20 Ethnic African Roots for Cape Verdeans (Cabo Verde Raizes Na Africa)

This research outcome from Verdu et al. clearly demonstrates the added value of expanding Upper Guinean reference populations in DNA testing. Beyond the limited and overused (also currently by AncestryDNA) Senegalese Mandenka samples. As I have argued in my latest blog post but actually also already in 2015 based on the available sampling from Jallow et al., 2009. I therefore fully concur with the suggestion being made in Verdu et al. that especially the inclusion of Wolof samples might benefit an even more adequate genetic analysis of Cape Verde’s Upper Guinean heritage.

I find it very unfortunate that this study offers no detailed statistics beyond its charts. It would have given greater insight into the exact admixture proportions of their Santiago study group (n=44). When Verdu et al. are stating that Cape Verdeans are “a combination of Iberian and Senegambian sources“, this is of course very similar to my own current survey findings (n=100, with various island origins). Also in regards to the mostly Iberian origins of Cape Verdeans (see section 5). But it still lacks the regional detail of AncestryDNA’s Ethnicity Estimates enabling the detection of for example West Asian and Jewish lineage as well as a minor degree of possibly non-Upper Guinean lineage. All of which prevents evenhanded comparison.

Upper Guinean origins around 1572-1634

____________________

“Although most captives listed in Table 1 [7] were acquired south of the Gambia River, several bore ethnonyms indicating Senegambian origins. The presence of individuals, albeit few, described as “Jolofo” on the San Pedro, San Jorge, San Josephe, and the Concepcion and others described as “Berbesi” on the San Pedro and San Josephe reveals that the transatlantic slave trade from Upper Guinea and the Cape Verde Islands drew on slave catchment areas extending perhaps as far north as the Senegal River. One captive arriving in Havana on the San Pedro in 1572 was described as a black woman from Arguim (“Argui”), an island off the Mauritanian coast, even farther north.” (D. Wheat, 2016, pp. 30-31).

____________________

Table 8 (click to enlarge)

Table taken from “Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570-1640” (D. Wheat, 2016, p.32). Additions in red are mine. I encircled the three most frequently named ethnicities: the Bran/Brame (=Papel) & Beafara/Befada from Guiné Bissau, as well as the Zape from Sierra Leone.

***

In my blog article of 2015 (section 2) I already gave a detailed specification of the most likely ethnic groups in regards to Upper Guinean lineage for Cape Verdeans. Based on historically documented overviews for the most part. I also emphasized how time framing is essential to distinguish northern Senegambian origins from Guiné Bissau/Casamance origins. As well as other less prominent but still important origins from Guinea Conakry, Sierra Leone, Mali & Mauritania. A relative shift taking place in localized slave trade patterns comparing the very first century of Cape Verde’s settlement (1460-1560) with the second one (1560-1660) as well as following time periods when slave trade decreased drastically. All of this due to the arrival of other competing European powers on the scene. Which caused Cape Verde’s once extensive regional networks to be confined to Guiné Bissau & Casamance eventually. In regards to the quotation above it is therefore very relevant to keep in mind that prior to the sample period of 1572-1634 the frequency of northern Senegambian origins is likely to have been much greater.

In 2016 the historian David Wheat wrote an extremely insightful book describing the Spanish Caribbean as an extension of the Luso-African Atlantic world, incl. Cape Verde! Especially table 8 shown above is a very precious source to gain ethnic-specific understanding of Cape Verde’s Upper Guinean roots within this particular period (1572-1634). It is based on the detailed records of 505 captives travelling on 5 slave ships departing from Cape Verde in three cases and otherwise from Guiné Bissau. All of these people could therefore also easily have remained in Cape Verde! Given that the local demand for slave labour at time was still quite strong. The most frequently mentioned ethnic groups being the same ones I have already explored elsewhere on this blog and my Cabo Verde Raizes Na Africa website. For more details I highly recommend reading David Wheat’s book: “Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570-1640”

- Ethnicities of Upper Guinean Slaves (Cabo Verde Raizes Na Africa)

- Map showing Upper Guinean ethnic groups circa 1580 (D. Wheat, 2016, p. 28)

- Upper Guinean Ethnonyms in Slave Ship Rosters (D. Wheat, 2016, pp. 27-53)

4) Beyond Upper Guinea: valid outcomes or misreading by AncestryDNA?

Figure 5 (click to enlarge) Maximum regional scores

These screenshots are showcasing the maximum scores among my survey participants for each African region available on AncestryDNA. It therefore illustrates them in an extra pronounced degree. Aside from “Senegal” and “Mali” these regions were usually being reported as low confidence trace regions though. See also: Maximum scores among the Afro-Diaspora

***

Table 9 (click to enlarge)

This table showing various statistical details for my 100 survey participants is very similar to my findings from 2015 (n=23), see this chart. The main difference being the maximum values although on average the scaled African breakdown has remained consistent.

____________________

“it might therefore perhaps be premature to speculate on what these findings might really represent or how robust they might be. They might merely be reflecting generic West African DNA markers which cannot be distinguished yet with greater reliability. Or it could be a misreading of ethnic origins from especially Sierra Leone. Probably only an update of AncestryDNA reference populations might bring more clarity or else comparing with the AncestryDNA results of actual Upper Guineans (to verify if they also show other regions besides “Senegal” and “Mali”) .” (Fonte Felipe, 2015)

____________________

In my 2015 discussion of Cape Verdean AncestryDNA results I already mentioned the somewhat unexpected high level of African regions not directly to be associated with Upper Guinea. That is “Benin/Togo”, “Nigeria”, “Cameroon/Congo” and “Southeastern Bantu”. I even devoted a separate section (5) to that last region. “Ivory Coast/Ghana” and “South-Central Hunter-Gatherers” are arguably regions which despite the labeling can still be tied with Upper Guinean lineage for Cape Verdeans. In particular from Sierra Leone11. Fast forward to 2018 and I can already reveal that the upcoming update on Ancestry will quite likely eliminate some of these unexpected regional scores, seemingly indicating origins from either Lower Guinea or Bantu speaking Africa. But misleadingly so as it may turn out! I will discuss this in greater detail in section 7 further below.

On the other hand my ongoing survey of AncestryDNA results among both Cape Verdeans and actual Upper Guineans now allows me to delve somewhat deeper into the possible implications based on the current version of AncestryDNA. In particular the higher maximum values for these seemingly non-Upper Guinean regions among my 100 Cape Verdean survey participants. All clearly above trace level and no longer earmarked as “low confidence” by AncestryDNA (see figure 5). Although in fact the group averages have remained largely the same and are still subdued (see table 9 and also table 6). I would like to underline that this discussion will again by necessity be somewhat speculative. Especially in light of Ancestry’s upcoming update. But I believe it can still be useful to also explore these possibly broader African roots of Cape Verdeans.

The higher maximum values I observed among my Cape Verdean survey group are perhaps to be seen as atypical outliers. Whenever first confronted with such breakdowns I have always made an extra effort to verify if these survey participants were indeed of fully Cape Verdean descent. Not only to their own knowledge but also by looking into possibly other clues such as DNA matches and migrations they were assigned to on AncestryDNA. I performed such a quality check for all the screenshots I featured in figure 5. However I still cannot rule out the possibility that perhaps such scores are in some selected cases also caused by atypical family histories involving return or back & forth migrations to and from fellow former Portuguese colonies such as Angola, Brazil, São Tomé & Principe and Mozambique. And possibly also other migrant destinations (the USA being least likely because of the quality check I performed). Although again I did not come across any apparent clue for this and neither were the survey participants in question aware of such connections.

Table 10 (click to enlarge)

This table is contrasting the scaled African/SSA breakdown (“Africa North” is excluded!) of my Cape Verdean survey group with 5 samples from Senegal & Gambia. Despite minimal samplesize and overall similarity minor deviations might be indicative of lineage from beyond Senegambia. For a similar overview specifying my separate findings for Brava, Fogo & Barlavento islands see this chart. The island origins of my survey participants are not based on a 4 grand parents criterium per se. As many people were not fully aware. See also footnote 6.

***

In such cases as well as other ancestral scenarios involving sailors, travellers etc. I suppose the involved African geneflow would not be representative for the Cape Verdean genepool in general. Or at least it would not be traceable to the earlier settlement period of Cape Verde (1400’s-1600’s) but rather to the late colonial phase (1800’s/1900’s). Then again looking at the more detailed group averages shown in table 9 several preliminary tendencies might be distinguished. Regrettably I had only a few suitable Upper Guinean samples available to compare with12. But it is probably already telling that the scaled “Senegal” group average (63%) for my Cape Verdean sample group, eventhough rather high, is still at some distance from the 79% “Senegal” group average for my Senegambian samples. The “Mali” and “Ivory Coast/Ghana” group averages are quite similar. But the relatively greatest deviations occur for “Benin/Togo”, “Nigeria”, “Cameroon/Congo” and “Southeastern Bantu”. Possibly indicating that these are indeed regional scores to be explained by additional African roots from outside Upper Guinea. Or more properly Senegambia. Including more results from Guinea Bissau/Conakry would naturally have provided a more complete perspective.

It is intriguing to then also take into account the various island origins of my survey participants. In 2015 I already cautioned about how the minimal sample size might skew the group averages. Which is why I have decided to only use broader groupings “Barlavento” and “Brava & Fogo” aside from still also including 3 samples from Santiago in table 9. Of course other shortcomings might remain in place but still some of the deviating regional patterns caused by inter-island differentiation (see Beleza et al., 2012) might now have become more visible. What stands out to me the most when compared to my findings in 2015 (see this chart) is the following:

- In regards to the “Senegal” and “Mali scores. These are quite similar across the board. Except for the still somewhat elevated “Mali scores for especially my Brava samples (19.5% without Fogo included, see this chart). Perhaps implying something about a slightly different composition of their Upper Guinean origins. But maybe also just an artefact of Ancestry’s algorithm not being equipped to make a proper distinction for people with relatively lower African amounts (the same might be true for Mexicans and other Hispanics too actually).

- The “Ivory Coast/Ghana” group average is highest for my Santiago samples but this is mostly due to one result with 20% for this region. As described in footnote 11 this seemingly atypical score is still very likely to be indicative of either Guinean or Sierra Leonean origins.

- “Benin/Togo” group averages are similar across the islands. But there is some increased level of “Nigeria” as well as “Cameroon/Congo” among my Barlavento samples. Caused by not only one but several outliers in fact. Barlavento islanders being behind most of the maximum scores featured in figure 5 (also for “Benin/Togo” and “Southeast Bantu”).

- The “Southeast Bantu” group average does no longer stand out in the same way as it did in 2015. There is also no strong island variation. However it is still clearly elevated when compared with actual Senegambians (0.2%). As well as when comparing with Fula people on a similar footing (incl. “Africa North”). Fula people do at times score considerable amounts for this region (to be explained by genetic similarities with Northeast African DNA). But on average still lower than Cape Verdeans (2.8% for 43 Fula samples versus 5.2%, see table 7). Increasing the odds of potential Angolan/Mozambican connections, when reported in above average amounts. But still to be validated by follow-up research.

In summary the best way to corroborate these seemingly non-Upper Guinean findings might be to just simply await the upcoming update on AncestryDNA13. Otherwise it may still be worthwhile to also do a thorough check of your DNA matches as well as pay closer attention to the migration stories in your family tree research. Then again more historical research might also be helpful in making sense of such scores. As I mentioned in 2015:

“the documentation of ethnic origins in Cape Verde is very fragmentary, especially for the earlier timeperiods when it functioned as a slave trading hub“. And

“Cape Verde was used as a stopover for the main sailing route between Portugal on the one end and São Tomé, Brazil, Mozambique/Asia on the other.“

In my reading of Cape Verdean and Afro-Diasporan history I did actually at times come across specific historical references to African captives outside of the expected Upper Guinea area being present in Cape Verde. I will try to create a new section on my Cabo Verde Raizes Na Africa website to provide an overview of such references.

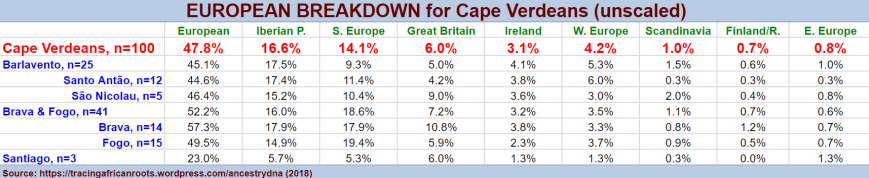

5) European breakdown reflecting mostly Portuguese ancestry?

Table 11 (click to enlarge)

This table is showing the statistical details for the European scores of my Cape Verdean survey participants. Based on the original amounts, so unscaled. Take note how despite seemingly diversity “Iberian Peninsula” and “Europe South” are clearly predominant. As is also the case for Portuguese, see this chart.

***

Figure 6 (click to enlarge)

Selection of AncestryDNA results for persons who are fully Portuguese to my knowledge. Take note how socalled “Italy/Greece” a.k.a. “Europe South” is very commonly reported for Portuguese people. Sometimes even as primary region! But in fact also minor but still considerable amounts of “Great Britain”, “Ireland”, “Europe West” etc.. See this page for more details: Iberian AncestryDNA results.

***

As already shown in the beginning of this page (chart 1) the main regional European scores for Cape Verdeans on AncestryDNA have been “Iberian Peninsula” and “Europe South”. This latter region formerly known as “Italy/Greece” (causing many people to be mislead). Based on having the biggest amount within the European breakdown “Iberian Peninsula” (50/100) is slightly more significant than “Europe South” (36/100). But it is a more balanced outcome when going by group averages: 16.6% versus 14.1% (see table 11). In addition my Cape Verdean survey participants have also received many other European regional scores. Often also as main region and not just a low confidence or trace region. In some cases even being reported as the primary region within the European breakdown. This happened seven times for “Europe West”, six times for “Great Britain” and one time for “European Jewish” (Jewish admixture will be discussed in section 6).

Many people are confused and often also mislead by their European DNA results. This happens because they tend to take the regional labeling too literally. Ignoring the geographical & genetic overlap of AncestryDNA’s regions. However in most cases receiving a multitude of European (trace) regions does not imply that you have a confusingly diverse European background! Rather it suggests that your European ancestors were themselves genetically diverse. But still these ancestors could have been from just one or two ethnic groups only. In the case of Cape Verdeans: principally Portuguese.

Because of ancient migrations and ongoing ethnogenesis it can be said that European DNA is also a melting pot if you go back far enough in time. Figure 6 is highlighting for example how the “Iberian Peninsula” region is not equipped to cover the full extent of Portuguese origins. Additional regions being required as well, especially “Europe South” (a.k.a. “Italy/Greece”). For correct interpretation it is essential therefore to be aware of how native Europeans themselves are described by AncestryDNA. The same principle is valid of course for a better understanding of African and other continental scores as well. Unlike other DNA testing companies AncestryDNA actually provides very useful information in this regard (see this link). However I have chosen to also make use of my own findings from a survey among actual Europeans which I have been conducting specifically for this purpose. For more details see:

Table 12 (click to enlarge)

In this table I have scaled the European breakdown of my Cape Verdean survey group to 100% in order to compare it more easily with other nationalities. We can verify that the scaled European breakdown of Cape Verdeans mirrors the one for Portuguese (and also Brazilians) quite closely.

***

In table 12 I have calculated how the scaled14 European breakdown of my Cape Verdean survey group compares with the group averages of several other nationalities in my AncestryDNA survey. The European countries I selected in table 12 represent the most likely source candidates for the European DNA detected among my survey participants. Based on the colonial history for each of my sample groups. Of course this is not to deny or rule out any additional and also post-colonial European migrant lineage from other countries. In individual and documented cases this may be very relevant even. At this point I am however principally concerned with finding more generalized tendencies.15

Despite obvious sample size limitations I find it remarkable how closely my sample groups resemble their historically plausible European source populations already. In particular the scaled European breakdown of Cape Verdeans mirrors the one for Portuguese quite closely. This goes too for my Brazilian samples (who are overwhelmingly Afro-descended people with colonial Brazilian roots and not including any Italo-Brazilians, see this link). My Hispanic sample groups are showing a somewhat higher degree of “Iberian Peninsula”. Which is in line with this region being most predictive of (northern) Spanish DNA, generally speaking. While my Brazilian and Cape Verdean sample groups are showing a more pronounced degree of “Europe South” (even more so when measured by top ranking frequency, see this chart). Which is in line with the results of actual Portuguese. Again other ancestral scenarios are not to be ruled out (genuine Italian or Sephardi Jewish lineage). However just based on how actual Portuguese DNA is being described by AncestryDNA this outcome already makes much sense within itself. For more detailed discussion see:

Based on these (preliminary) findings it seems to be implied that for many of my Cape Verdean survey participants the “Europe South” scores are being inherited from Portuguese ancestors, atleast for the most part. In fact this probably also goes for much of the “Great Britain”, “Ireland” and “Europe West” scores. Unless reported in an atypically high degree (deviating from Portuguese group averages) and/or in accordance with known family history involving non-Iberian lineage. Actually there are two further arguments in favour of a Portuguese interpretation:

1) The rather elevated frequency (16/88) of Cape Verdeans being assigned to the “Portuguese” migration on AncestryDNA. While my Cape Verdean survey particpants have not been assigned to any other European migration, aside from once a “Spaniards” migration. It is very telling also that AncestryDNA mentions itself that this “Portuguese” migration assignment is based on regional scores for not only “Iberian Peninsula” but also “Europe South”! See this screenshot:

***(click to enlarge)

***

2) The research outcome of Verdu et al. (p.2530, 2017) which states that:

“most Cape Verdeans lie on a path connecting Senegambian populations to an Iberian sample, rather than to British or French populations. That Iberians represent the most suitable proxy for the European ancestry of Cape Verdeans is compatible with records of the Portuguese slave trade in Senegambia starting early in the history of Cape Verde [41–43] and accords with an understanding of Cape Verdean Kriolu as a hybrid of Portuguese with languages from the Senegambian region”.

See also this chart taken from that study.

Indications of non-Portuguese lineage: maximum regional scores & inter-island variation

Figure 6 (click to enlarge)

These screenshots are showcasing the maximum scores among my survey participants for a few selected European regions. It therefore illustrates them in an extra pronounced degree. Aside from “Iberian Peninsula” and “Europe South” the other European regions were usually being reported in single digit amounts though or even as low confidence trace regions.

***

Based on the previous discussion it seems reasonable to assume that the European origins of Cape Verdeans are for a greater part Portuguese. In line with their colonial history. However settlers or temporary residents with other European origins have also been historically attested for Cape Verde, albeit to a lesser degree. Generally speaking within this current version of AncestryDNA it has proven to be quite difficult to make the distinction between ancient geneflow and more recent genealogical geneflow. For example due to shared ancient Celtic and Germanic migrations across western Europe the Portuguese themselves also very frequently receive considerable scores for “Europe West”, “Great Britain” and “Ireland” etc.. This type of DNA has been firmly incorporated within their genepool so to speak but still is to be traced back to ancient times! However when a Cape Verdean in turn also receives such seemingly West European scores how do we determine if this DNA has been inherited from West European ancestors within a genealogically meaningful timeframe (~500 years) rather than passed on by Portuguese ancestors who also tend to have the same DNA markers?

Instead of blindly relying on the regional labeling of admixture results it is recommendable to always also perform follow-up research. Including but not restricted to: local history to determine plausibility; diligent family tree research and a thorough analysis of one’s DNA matches. The upcoming update of AncestryDNA is also bound to provide more clarity (see section 7). Then again some of my survey findings already seem to be more solidly in support of non-Portuguese lineage. In particular the maximum values I have observed for regions like “Europe West” and “Great Britain”. The top ranking frequency of these two regions also being greater among my Cape Verdean survey group than for my other survey groups (Brazilians & Hispanics) with similar Iberian background (see this chart).16 It also seems striking that the maximum value for “Europe South” (46%) should be considerably higher than for “Iberian Peninsula” (31%) among my 100 Cape Verdean survey participants (see figure 6 & table 11). However without additional clues any conclusive statements cannot be made, as several ancestral scenario’s might still be applicable all at the same time.

Table 13 (click to enlarge)

This table is showing some of the inter-island variation among my survey participants. Keep in mind that the original regional scores have not been scaled. All other things being the same one might therefore expect that my samples from Brava would have the highest regional group averages for each region. But intriguingly this is not the case. The island origins of my survey participants are not based on a 4 grand parents criterium per se. As many people were not fully aware. See also footnote 6.

***

Another indication (again nothing conclusive!) seems to be forthcoming from the inter-island variation shown in table 13 above. Obviously sample size is quite minimal but it still seems noteworthy that especially Fogo islanders tend to have more “Europe South” on average than “Iberian Peninsula”. While it is the opposite especially for Barlavento islanders. The ratio of these two interrelated regions being most balanced for Brava. This outcome could possibly be suggesting a greater degree of Portuguese lineage for the Barlavento islands. While for Fogo possibly a greater degree of Sephardi Jewish lineage and perhaps also genuine Italian ancestry might be suggested, both mainly to be traced back to the 1500’s. In line with their earlier settlement history. As well as the circumstance that socalled “Europe South” really seems to be a generic genetic component found all across the southern Mediterranean, incl. not only among Portuguese but also Sephardi Jews (see this screenshot and section 7 for further discussion).

In regards to the regions possibly suggestive of western European lineage (“Europe West”, “Great Britain”, “Ireland”, etc.) the inter-island variation is less apparent. When going by group averages that is. However it might perhaps not be a coincidence that many of the “Europe West” and “Great Britain” outliers were obtained for persons from the Barlavento islands. Especially intriguing to take into account the stories of pirates from Great Britain, France and the Netherlands sometimes settling and intermarrying with local women on Barlavento islands (see entry for 1700 in this overview). Although such stories are probably not exclusive to the Barlavento. As contraband trade (salt, pano textiles etc.) with West Europeans and especially the English was rampant on other islands as well. Otherwise most maximum scores for the other European regions were received for people from Brava. Which would be in the line of expectation as Brava islanders had the greatest degree of European DNA on average in my survey. See also:

- The British Presence on the Cape Verdean Archipelago (Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries) (M. Soares, 2011)

- Montrond generations (photo shoot of the descendants of a Frenchmen who settled in Fogo in the 1870’s) (Viola Berlanda)

6) “Africa North”, “Middle East”, “European Jewish” and other minor regional scores

Table 14 (click to enlarge)

This table shows the statistical details of regions which usually were reported with low confidence, a.k.a. trace regions. However not always! Take note of the maximum values especially. The number of times a specific region did not show up at all in the breakdown is measured by “# 0% scores”

***

Figure 7 (click to enlarge)

This selection shows the maximum values obtained by my Cape Verdean survey participants for the encircled regions. The screenshot in the bottom right corner perhaps being most illustrative as it shows all these regions in rather elevated degree, aside from 7% “Caucasus”.

***

In this section I will discuss the regional scores which were generally speaking only being reported as “low confidence” or “trace region” for my Cape Verdean survey participants. The labeling by AncestryDNA itself already indicates that only a shaky basis exists for the appearance of these scores (see also this link). Often such results are therefore dismissed as just statistical “noise”. Rightfully so in many cases. But given correct interpretation and proper follow-up research at times these scores can still potentially lead you to distinctive ancestors as well! Each case to be judged on its own merits. Based on table 14 we might already find justification to regard the “Africa North”, “Middle East” and “European Jewish” scores as quite robust. Because in fact these regions were often also reported above trace level. For the remaining regions we can see from the average and median scores that generally speaking these were rather trivial results. In fact most of the time these regions, especially “Pacific Islander” and “Native American” were not reported at all (“# 0% scores”). Overall being very rare and therefore highly atypical outcomes for my Cape Verdean survey group.

***

Table 15 (click to enlarge)

This table is based on my ongoing survey of AncestryDNA results around the world. Featuring the group averages among the most likely source populations for “Africa North” and “Middle East” scores when reported for Cape Verdeans.

***

Figure 8 (click to enlarge)

These screenshots show a selection of plausible source population for “Africa North” and “Middle East”. Take note that the (mixed) Sephardi result does not show any substantial “Africa North” but it does include high “Europe South”, “Middle East” and “Caucasus” amounts

***

In my 2015 discussion (section 4) of Cape Verdean AncestryDNA results I already gave a detailed account of where the “Africa North” scores might possibly hail from when reported for Cape Verdeans. Describing at least 4 ancestral scenario’s involving direct or indirect inheritance by way of either Portuguese, Fula, Sephardi Jewish or Mauritanian/Moroccan ancestors. I will now also include “Middle East” in this discussion as this is in fact a closely related region for “Africa North”. Table 15 shows the group averages for both regions among the most plausible source populations for these DNA components (when appearing in the AncestryDNA results of Cape Verdeans). Regrettably I was not able to also include Sephardi Jews or Mauritanians for lack of samples. But otherwise the picture arising seems to be rather clear already. All three selected populations indeed being likely to have passed on such markers as they all possess them in sufficient degree. It must be noted though that similar to the “Iberian Peninsula” region the “Africa North” region is not perfectly predictive. Given the complex (pre)history of North Africa genetic affiliations with neighbouring populations to the east (“Middle East”) and also the southern Mediterranean (“Europe South” and “Iberian Peninsula”) are often expressed in the AncestryDNA results of actual North Africans. For more details:

- North African AncestryDNA results

- Fula AncestryDNA results (spreadsheet)

- Portuguese AncestryDNA results (spreadsheet)

In 2015 I cautioned that definite answers to the question how these regional scores are to be explained may not be provided yet. Especially given that “individual family trees will also stand in the way of a “one size fits all” narrative.” Still going by what I discussed in the previous section 5 I do now have additional reason to believe that generally speaking an indirect inheritance by way of Portuguese ancestors might be most relevant for Cape Verdeans. Take notice for example how in table 14 the group average for “Africa North” among 32 Portuguese (5.5%) is nearly twice as high as it is among 100 Cape Verdeans (2.9%). This would make sense given that my Cape Verdean survey participants are also on average about half European genetically speaking. Such reasoning is reinforced by the fact that the highest “Africa North” scores were usually obtained by my Cape Verdean survey participants with increased level of European admixture. Furthermore these people were very often being assigned to the “Portuguese” migration!

But this positive correlation with Portuguese admixture did not always manifest itself. Especially not for “Middle East” scores. In fact the group average for “Middle East” among Cape Verdeans (2.3%) is higher than among Portuguese (1.5%). Not by much but even more so when correcting for African admixture. Leading me to assume that additional ancestral scenario’s might exist. In particular a Sephardi Jewish connection may be suggested in several cases. Even though I have only seen very few Sephardi Jewish results it is likely that on average they will show substantial amounts of “Middle East” in their breakdown as well as “Europe South” actually (see figure 8).

On the other hand it cannot be ruled out either that in individual cases also Fula ancestry might still (partially) be responsible for both “Africa North” and “Middle East” scores among Cape Verdeans. As shown in table 14 the Fula people actually possess these DNA markers to a greater degree than Portuguese. Fula ancestors are also perfectly plausible as they have been present in Cape Verde from the early 1500’s. Despite lack of detailed data I do think it is safe to say that the average proportion of Fula ancestry among Cape Verdeans will be far lower than the average proportion of Portuguese ancestry. Given that the Upper Guinean roots of Cape Verdeans are multiple and varied and not restricted to just one ethnic group (see Top 20 ethnic roots). So in that way the odds of a Fula ancestral scenario might be decreased but nonetheless still valid!

Obviously more corroborating evidence needs to be forthcoming to confirm any of these speculative scenario’s. Also the upcoming update of AncestryDNA, especially by introducing a new “Portugal” region, might very well reduce or even eliminate some of these regional scores (see section 7). In the meanwhile however from my experience a very promising avenue of follow-up research would be to systematically scan your DNA matches. To see if any Portuguese, North African, Fula or Sephardi Jewish DNA matches show up. I have actually already done this for 50 of my Cape Verdean survey participants (using my filtering method in Excel) and I will report the outcomes in greater detail in my next blog post. I can already reveal that all of these aforementioned matches are indeed being reported for Cape Verdeans. Albeit with different frequency and also differences in shared segment size.

- DNA matches reported for 50 Cape Verdeans on AncestryDNA (part 1)

- How to find those elusive African [and European] DNA matches on Ancestry

Jewish admixture impacted by dilution?

Table 16 (click to enlarge)

This table is showing the group averages for the specified regions. Also according to island background. The island origins of my survey participants are not based on a 4 grand parents criterium per se. As many people were not fully aware. See also footnote 6.

***

In table 16 the group averages for “Africa North”, “Middle East”, “European Jewish” etc. are also being shown as specified by island (grouping). Potentially an interesting research field given founding effects from particular settlers who may have been more numerous in certain islands than others. For example exiled Mourisco’s or Conversos. However at this stage not much island variation is showing up. Atleast not very statistically meaningful. Especially given that the sample size for Santiago is very minimal. Still it seems that “Africa North” is slightly peaking for not only Brava but also Fogo and interestingly Santiago. Santo Antão had quite a few high “Middle East” outliers, but interestingly again Santiago has a rather elevated group average as well. While “European Jewish” sofar is rather evenly spread and generally subdued across the islands.

Unlike you might have expected the overall level of “Africa North” or “European Jewish” for my Cape Verdean survey group actually is not very striking when compared with the Portuguese or other nationalities I have included in my AncestryDNA survey. Although it does stand out when compared with survey groups without an Iberian background, such as African Americans. And again also the maximum values must be kept in mind. See also:

Within my Cape Verdean survey group there were at least 4 (unrelated) persons with confirmed Moroccan Jewish lineage from the late 1800’s. Two of them shown in figure 7. Some of these persons did indeed show rather high “European Jewish” scores, up to 9%. But on average for these 4 people “European Jewish” was around 5%. Indicating the generally rapid dilution of DNA when originating from one single family line. After 7 or 8 generations the genetic inheritance from one single ancestor might actually already not be detectable in DNA testing, especially with unfavourable recombination. This is sometimes called a genetic “wash-out” and comparable to the very minor or even absent Native American admixture results being reported for many Americans. Who are often shocked by this outcome because they were expecting much more based on family lore. See also:

I still have reason to believe however that “European Jewish” is not a perfect indicator of Sephardi Jewish lineage because it is first most describing genetic similarity with Ashkenazi samples (from East Europe). Despite shared origins the Sephardi Jews still having a diverging genetic make-up because of their different Diaspora experience. First in Portugal & Spain and then into Morocco. Ashkenazi genetics perhaps standing out as more distinctive. Again I have not seen that many complete AncestryDNA results of Sephardi Jews (the one shown in figure 8 is mixed Ashkenazi & Sephardi). But I have seen several in profile preview whereby only regional ranking is visible. And from those observations I think it is very likely that they are described by AncestryDNA as a combination of “Europe South”, “Middle East” first most with “European Jewish” actually often being secondary or subdued and also “Africa North” often being entirely absent.